Slave, conquistador, and the first African in Texas

“As long as the concept of an African-American is current and as long as African American history is seen as beginning with enslavement in Africa, then Esteban is important because he is the first African-American.”

— Robert Goodwin, historian and author, “Crossing the

Continent, 1527-1540, The Story of the first African-

American Explorer of the American South”

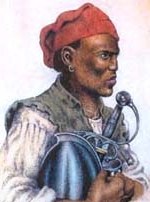

Esteeban

Andres Dorantes de Carranza was a young Spanish soldier when he began hearing colorful stories about adventure and fortune in the New World that piqued his curiosity and left him yearning for an opportunity to get a first hand look. To begin his quest, he secured an appointment as a captain on the Panfilo de Narváez expedition to explore and colonize for Spain territories along the Gulf Coast, beginning in Florida and extending to the Rio Grande. Narváez led five ships from Sanlucar de Barremeda, Spain on June 17, 1527 with 600 brave souls eager, like Dorantes, to claim riches, fame, and whatever else the New World had to offer.

However, seven years prior to the expedition, Dorantes had purchased a personal slave from a Portuguese enclave on Morocco’s Atlantic coast.

Esteban, (aka, Estevanico, Estebanico, Esteban Dorantes, Black Stephen, and Stephen the Moor, al-Zemmouri – the man from Azemmour), a Muslim from North Africa, had been enslaved at an early age by the Portuguese, and in 1520 became Dorantes’ property when both men were in their 20s. Esteban’s fate, however, was beyond servitude though his most pressing concern, in November, 1528, would be surviving a stormy ride in one of several crudely-made, shallow boats being tossed about in the wildly undulating surf of the Gulf of Mexico. When he and about 80 others, including Dorantes, Alonso Castillo Maldonado and Álvar

Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, finally waded ashore near what is now Galveston Island, the first European explorers had set foot in the territory that would become Texas.

And so had the first African.

It was a soggy, chilly landfall for what would be an eight-year odyssey for Esteban and company that would have them walking a trailblazing path from the central coast of Texas to Mexico City, a journey that would firmly establish Esteban as the first Black Texan, and as the first African American. He would also be acknowledged, by some, as the first non-native to enter what is now Arizona (possibly) and New Mexico. His arrival in Texas didn’t open the floodgates for Africans immigrating to Texas – no matter the circumstances, in fact there were no other reported Africans in the territory for almost two centuries (until 1691) before

another Spanish expedition found people of African heritage, possibly the survivors of other expeditions or shipwrecks, living with Indians near the mouth of the Rio Grande.

Alonso Alverez de Pineda had explored and mapped the Texas coastline in 1519, but the survivors of the Narváez expedition would set out from there and into the interior on a grand adventure that would become a remarkable tale of survival and a severe test of the human spirit. Their trek across Texas, encountering both friendly and hostile Indians, was nothing if not implausible.

For much of their journey, they were bare foot, naked, at times severely starved, yet the four intrepid men – including Esteban – would indeed walk through dense vegetation, rugged mountains and other challenging terrain unknown to them, from Galveston to Mexico City. Along the way, they would become godlike “children of the sun,” as the curious Indian tribes would dub the strange men who performed medical miracles (did Cabeza de Vaca really raise a man from the dead?) and became revered shamans with literally thousands of followers.

Their tales would be incredulous, and even Cabeza de Vaca would explain in his narrative, La Relación (the account): “I wrote it with great certainty that though many things are to be read in it, and things very difficult for some to believe, they may believe them without any doubt.”

And Esteban became a central figure. He was along as Dorantes’ slave, but as the journey unfolded, Esteban would become a scout and diplomat, often making the initial contacts with new tribes the men encountered, and acting as the lead communicator because of his noted skill for quickly picking up new languages and using sign languages.

Yet, in the two main accounts of the ordeal – Cabeza de Vaca’s narrative, La Relación, and the Joint Report delivered in Mexico City to Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain – Esteban’s contributions are marginalized. There is no formal account from Esteban and given his status as a servant none was expected. It is conjectured that the accounts from Cabeza de Vaca and Dorantes were written, in part, to glorify their bravery and discoveries hoping to elevate their status and gain favor with the Spanish Crown for future explorations and governorships in the New World. There are other flaws in their accounts, as well, including contradictions and omissions on locations, distances, dates, activities, and their route, in general, has been widely debated.

However, any hope that Cabeza de Vaca had of returning and further exploring the New World were immediately dashed when he was informed, upon his return to Spain, that such a commission had already been granted to Hernando de Soto who would indeed explore Florida and the Southeastern territories as well as Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas. Some credit him as the discoverer of the Mississippi River.

So, there is no direct account from Esteban and he doesn’t become a focal point of the explorations of Northern Mexico and the Southwest until after he is sold by Dorantes in Mexico City to Mendoza and leads Fray Marcos de Niza’s expedition to find the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola and their supposed abundance of gold and other treasures. For all that he and the others had survived in their previous travels, for their fame among the Indians, for Esteban’s proficiency as a communicator, this journey would end in his death, “full of arrows,” outside a village in Hawikuh in northern New Mexico at the hands of the very wary Zuni

Indians in 1539.

Read historian Rayford W. Logan’s essay “Estevanico — Negro Discoverer of the Southwest: a critical reexamination , ” in which Logan addresses the questions of Estevanico’s race (African or European?) and his death. The essay appeared in 1940 in one of the first editions (Vol. 1, No. 4) of the scholarly journal “Phylon,” a

publication started and edited by W.E.B. DuBois at Atlanta University. Logan received his doctorate in history from Harvard in 1936 and went on to a distinguished career at Howard University where he became one of the foremost black scholars and intellects of the 20th century. It was said of Logan that he “wrote and otherwise taught about the history of black people in this country many years before it became fashionable to do so.”

For further reading about Esteban:

- Estevanico the Moor — History.net feature story

- Esteban of Azemmour and His New World Adventures — Saudi Aramco World Story

- Dr. Robert Goodwin discusses his book “Crossing the Continent, 1527-1540: The Story of the First African-American Explorer of the American South” (HarperCollins)

- Estevanico — TSHA article

- Estevanico — Elizabethan Era website

- Estevanico, 1503-1539 — Las Culturas

- History 313: History of African Americans in the West — Dr. Quintard Taylor, Univ. of Washington

- Southwestern Writer’s Collection: Cabeza de Vaca’s “La Relacion”