By Anthony R. Jerry, Casey Melnik, Laura Hasbun, and Mauricio Javier Mendoza (Photos by Laura Hasbun)

(Included here are 30 food recipes and 39 medicinal recipes from the communities of the “Costa Chica” region.)

Currently, African descendants in the Costa Chica region of Oaxaca and Guerrero, as well as throughout Mexico more broadly, are involved in a project, some might even say movement, for cultural recognition. This project of cultural recognition has required that a number of stakeholders join the discussion about what it means to be black, and to ultimately define the cultural and racial parameters of blackness in Mexico. These stakeholders have included, local NGO’s, local and state government officials, local activists interested in issues of racial discrimination, as well as local community members who have found themselves confronted with the political question of “who are we?” Answering this question has not been easy.

The question of who are we, as all of the above-mentioned stakeholders have begun to recognize, is not simply a question of identity. Rather, answering this question has required a deeper look, on the part of all involved, into the historical issues surrounding race and culture that abound in Mexico. And, while these historical issues have been long silenced by the social and political strategies associated with mestizaje, the recognition of African descendants as one of Mexico’s recognized multicultural groups has meant that the reverberations of the colonial moment have once again become audible. The question of “who are we” is also a question of “where did we come from,” and, because of the historical silencing of blackness in Mexico, where did we ever go in the first place?

The silencing of African descendants associated with mestizaje in Mexico has made the process of cultural recognition for black communities distinct from that of the process used in officially approaching indigenous communities in previous eras. In fact, as black communities were seldom recognized to exist within Mexico in the contemporary moment, the recognition of culture within these black communities has in many ways meant the invention of culture. The use of the term invention is not to suggest here that the communities of the Costa Chica were ever “cultureless.” However, as blackness was so intertwined with the overall cultural development of Mexico, it is difficult to find many cultural forms that were not simply incorporated into mainstream regional cultures and allowed to exist simply as a regional form of Mexican-ness (glossed as mestizo), rather than distinctly “African based” cultural practices. While many have searched for particular “cultural survivals,” it is more common that African descendants, unlike the many indigenous groups in Mexico, have remained a community apart simply based on their racial characteristics rather than a complex of “unique” cultural traits.

However, the current project of recognition has had some impact on this process, and it is now evident that black communities throughout Mexico are searching through the rubble in order to make sense of the imperial debris (Stoler 2007) that can still be seen to exist as part of the multicultural present within Mexico. This making sense, as explained by Jonathan Warren (2001) in his Brazilian examples, is what is meant here by the term “invention.” In this way, African descendants are seeking new ways to represent themselves through culture, forms that in the past may simply have been taken for granted. And, as some have recognized the need to represent themselves culturally within the accepted paradigms of multicultural recognition and representation, the process of invention is making use of these taken for granted forms in an attempt to help define what it means to be black in Mexico.

The recipes that are highlighted here are part of this larger process of cultural definition as one component of the overall project for recognition. Many in the communities of the Costa Chica have recognized that, similar to indigenous communities in the area, cultural representation can be beneficial in a number of ways, and have therefore begun to think about how to define themselves in terms of culture. The recipes in this section are seen by some to represent the culinary traditions of the Costa Chica, and are therefore culturally representative of the black communities in the region. It cannot be argued that all of the recipes and the use of the ingredients are “distinct” or “unique” to these communities. However, in years to come, these recipes will undoubtedly be counted as part of the “material” culture of the region and the cultural group that is more and more becoming popularly known as the Afro-Mexican community.

Some of the dishes presented here are specific to the Afro-Mexican communities of the coast while others are seen throughout Oaxaca. In fact, many of these dishes will be recognizable as common throughout the many regions of Mexico. One of the differences, however, between the regions is the use of local ingredients and herbs, which give the dishes a distinctly local flavor. Examples of the substituting of local ingredients and the effect on local dishes are many. Take as two examples the use of the southern herbs Epazote and Yerba Santa to flavor meat, beans, sauces, and soups instead of the popular northern herb cilantro. The use of Epazote and Yerba Santa are common throughout Oaxaca. However, the use of these herbs is essential to the cuisine of the Costa Chica as well. Other examples would be the use of iguana, turtle, and other wild meats such as badger and armadillo, as well as the use of turtle’s eggs as an appetizer or snack food. Interestingly, the appropriation of some of these items, such as turtle and iguana are now prohibited in regions such as the Lagunas de Chacahuas national preserve. And, as local African descendants do not have recognized land claims similar to those of indigenous communities, they have little recourse in making claims to traditional cultural and territorial rights, known as “usos y costumbres” for indigenous communities. Therefore, African descendants run the risk of hefty fines and other sanctions from local authorities for the continued harvesting of these prohibited items. Nonetheless, they remain a part of the local diet in many of the communities of the Costa Chica region.

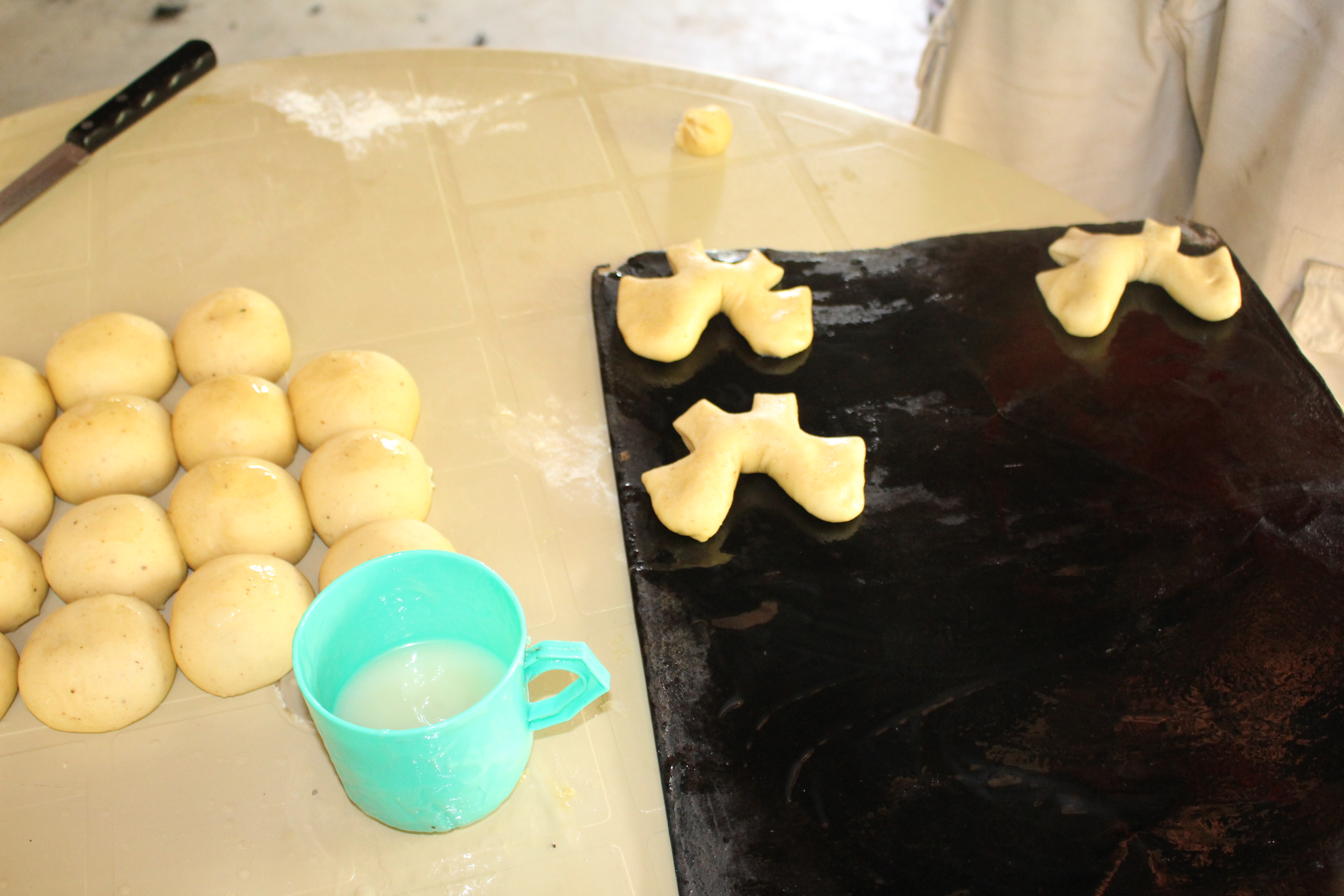

The recipes contained here come from three different women: Lucila and Juanita of Charco Redondo, and Paula of the island of Chacahua. Approaching Lucila’s home you find her gate always open. People come and go throughout the day, and more often than not, she is feeding her guests. Lucila’s stove and oven, like many seen throughout the region, are outside. The large structure is made of earthen clay and is fed by firewood from local tree species. The oven and stove, as well as a spacious sitting and eating area, rest under a large palapa made of wooden beams and dried palm leaves for cover. Chickens roam freely across the dirt floor crowing and seeking out food scraps.

Lucila lives with and cares for her elderly mother. It is her mother and grandmother who taught her most of the recipes she cooks today. In many ways, these women are remembered and brought back to life through the process of re-producing and cooking that takes place in Lucila’s outdoor kitchen. In addition to her cooking recipes, Lucila has extensive knowledge of the native plants that grow in Charco Redondo, and throughout the region, as well as how to use these numerous plant species as medicinal remedies for various ailments.

The staple ingredients in almost every recipe contained here include garlic, onion, and chili, with tomatoes not far behind. The term ‘a la mexicana’ in food includes these 4 ingredients, which represent the colors of the Mexican flag (red, white, and green). Many of the meat dishes presented here begin with a live animal from her own stock or the stock of nearby friends and relatives, and by the end of the day the meat has been prepared and eaten, while any left over scraps go to the other animals (pigs, chickens, and dogs). Chicken is rarely cooked, as the eggs are considered more valuable than the poultry.

Introduction to Photo Exhibit (PDF)