“Innovative Perspectives in Agriculture Development: The Role of Slavery and Land Grant HBCU’s in Texas Black Communities”

Na’Shon Z. Edwards, Sr, M.CD.

Community Development Researcher

Houston, Texas

Abstract

Institutions classified as Historically Black Colleges and Universities were consequences of the Agricultural College Act of 1890 (Castle and Christy,1992), which is also known as the Second Morrill Act (Castle and Christy, 1992). This act of Congress allocated resources to states to establish normal tertiary schools that focused on agricultural, industrial, and educational training for people of color. The Second Morrill Act provided emancipated slaves with the intellectual tools to contribute to the development of Texas agriculture by way of techniques, theories, and inventions often resulting in them becoming contributing members to their community. Today, the normal schools are now called HBCUs and continue their mission of cultivating and educating minorities in various disciplines. While HBCUs continue to thrive in spaces such as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts and Mathematics) programs, the emphasis on agriculture and its consequences on the institutions’ stationary community remain marginally unchanged. The 1890 agricultural colleges in Texas have accepted the challenge to meet the job market’s demand for qualified candidates in primary degree fields such as medicine and engineering, thus creating and widening the gap around the agriculture industry and the black community and control of food. This essay explores (1) how slavery aided in the agricultural development of black communities, (2) measures the social impact of Texas land grant HBCU’s and how they shaped their communities social structure, (3) and identifies whether agriculture can serve as a vehicle for the social fortification of dwindling black communities.

Background

In the latter portion of the 19th century, several historical events altered the trajectory of Texans as we have come to know it. The first is that the Confederacy lost its four-year war to the Union, leaving the southern infrastructure in turmoil and reconstruction because the south controlled the slave trade and subsidiary industries, of which agriculture was the largest. The primary consequence of the American Civil War was that slavery was abolished and slaves were no longer considered property. The former slaves were referred to as “freedmen” and had the opportunity to live their lives out of bondage and engage in behaviors that enabled them to experience their inalienable rights(1).

In 1862, Justin Morrill, a young Vermont legislator, observed that every American should have the right to education and the opportunity to improve their quality of life by pursuing a college degree to learn skills and techniques in such areas as home economics, agriculture, and various other trades. Thus, on July 2, 1862, he sponsored the passage of the first Morrill Act (officially called, “An Act Donating Public Lands to the Several States and Territories which may provide Colleges for the Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts”) granting states 30,000 acres of land and the task of establishing institutions that would teach citizens an array of techniques and methods concerning agriculture, farming, and education. However, southern states resisted applying that to Negro institutions, but Morrill felt that freedmen should be granted the same opportunities given their fellow Americans in the 1862 Act(2).

Almost thirty years later, in 1890, the Second Morrill Act, also known as the Agriculture College Act, was passed specifically to support Negro Land-Grant institutions, referred to today as “The 1890 Institutions.” Those Southern States which did not have Negro institutions by 1890 each established one later under this Act.

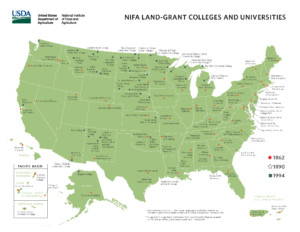

A consequence of both the 1862 and 1890 Morrill Acts was the creation of Land-Grant Universities in the majority of states in the Union. Until the early 1960s, the 1862 Land-Grant Universities have enrolled only Anglo-American students, while the 1890 Land-Grant Universities admitted freedmen. Today, these institutions have become known as Land-Grant Predominantly White Institutions (LG-PWI’s) and Land-Grant Historically Black Colleges and Universities (LG-HBCU’s) respectfully.

In Texas, there is one 1862 Land-Grant University, Texas Agricultural & Mechanical University in College Station, Texas, and one 1890 Land-Grant University, which is Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical University in Prairie View, Texas. Both universities are a part of the Texas A&M University System. Although these universities were founded only five years apart if one was to review the overall institutional demographics, community identity, and level of sprawl you may question how can these two conceptually similar institutions and their communities be worlds apart?

Alta Vista Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youth circa 1916. Left, Luckie Hall Dormitory (Smithsonian NMAAHC). Right, Kirby Hall, the first building on campus and the former main house of the Kirby Plantation (Courtesy of PVAMU’s Special Collections and Archives Department).

The Post Slavery Community and Agriculture

Before the abolishment of slavery in Texas, black communities revolved around plantations, with their slave quarters, working fields, and the plantation home also referred to as the “big house.” This infamous location served as the new black community in the south with its harsh social consequences and constructs serving as the “institution” of order for nearly two hundred years in Texas. Yet, post-emancipation, many of the freedmen struggled to completely sever ties with the plantation feeling it was their community and the opportunity to start a new life seemed beyond belief which is why some freedmen continued to live their lives as slaves. Infamously, they became indentured servants living near their former slave masters.

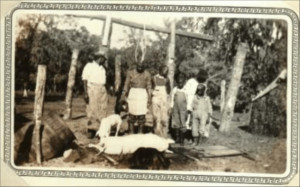

With indentured servitude on the rise in Texas, the practice of agriculture and its many systems catalyzed the establishment of the post-slavery black communities. In African cultures, marriage, and rituals were centered on some form of agriculture such as trading livestock for marriage arrangements or raising the largest cattle as a rite of passage. Those practices were carried through the Diaspora, though many were tradeoffs to slavery and new social conditioning. However, slaves developed innovative ways to implement agriculture in daily routines and customs, such as basket weaving, music, and religion.

Freedmen in Texas established unincorporated areas in growing cities, often referred to as colonies with names ending in ‘ville,’ ‘town,’ or ‘station.’ These colonies were often isolated and poorly documented, but many were able to develop their systems and means of life often mimicking the experiences they once had as slaves such as growing and trading staple crops with other freedmen within the colony(4) (Roberts, 2018). This trade typically allowed for slaves to develop strong ties with other families, which commonly resulted in marriages. Trade served as a vehicle for many freedmen to climb the southern black social ladder, create generational wealth, and establish themselves as viable farmers and businesspeople.

The history of former slaves in Texas after the Emancipation Proclamation is bleak, but some of the earliest black communities were Freedmen’s Town in Houston, Deep Ellum, Little Egypt, Shankleville, and Moore Station(5) (Roberts, 2018). These settlements, along with a growing list of many others, serve as historical footprints of former slaves. Unfortunately, many of these freedmen settlements did not survive because of migration, lack of economic stability, and incorporation of wealthy predominantly white settlements, which resulted in many freedmen losing valuable assets in the process including acres of land and livestock(6). With this aggressive form of displacement, rural black community residents were either forced to migrate to emerging cities in Texas such as Houston, Dallas, and Austin and settle in segregated communities that did not match the quality of life in their colonies, or they were faced with fatal consequences such as lynching and feathering(7).

The freedmen settlements consisted of four significant components music, religion, family, and agriculture, which can be attributed to slave customs that remained a part of the community. Of these four variables the most important was agriculture, and it is crucial to understand that agriculture and the black community should not be associated with merely cotton, but black community staples such as yams, potatoes, corn, wheat, collard greens, cattle, and chicken all relatively determined a black family’s station in that social bubble. However, with the rapid migration of Anglo-Texans to areas near black settlements, the economic practice of harvest and trade was disrupted dramatically, and consequently many communities began to lose their connectivity and identity in the process.

1890 Land – Grant & the Black Community

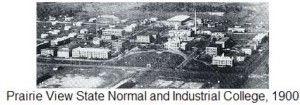

The only 1890 Land-Grant in Texas is Prairie View A&M University located just forty miles outside of Houston, Texas nestled in the growing city of Prairie View. The university is renowned for producing the nations’ top African American nurses, engineers, and architects respectfully and continues to grow in terms of institutional infrastructure and population. It is also important to note that Prairie View A&M University is the second oldest public institution of higher learning next to Texas A&M University. While Prairie View A&M University is impressive presently, it is imperative to reflect on the history of the university and its conceptual purpose.

Livestock management demonstration on butchering hogs, 1937. (Courtesy of PVAMU’s Special Collections and Archives Department, Agricultural Extension Collection.)

Before it was known as Prairie View A&M University it was named the Alta Vista Agriculture & Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youths because of its location on the site of the former Alta Vista Plantation owned by the Jared Kirby Family of Waller County. Through five legislative name changes and fifteen presidents, the university’s agricultural component has remained constant, practiced through its Cooperative Extension Program(8) which links the university to rural black communities. The purpose of the cooperative extension service is to educate those communities and agricultural producers on techniques to improve their quality of life, partnerships, and market trends in agriculture to increase the competitiveness of minority producers and their crops in Texas.

Not all black communities were casualties of the migration of Anglos in Texas; in fact, many of the black settlements and their agricultural producers flourished. However, after the increase in social, civic, and physical barriers such as the highways, black codes, Jim Crow, and urban sprawl, many of the producers sold their land. With the mounting social challenges facing the black community, many of the farmers opted to sell their property instead of passing it on to their rightful heirs, not because the practice of farming was expensive, but because the practice had become too rigorous and less lucrative for succeeding generations. According to Debra Reid, a faculty member at Eastern Illinois University, in the year 1910 there were a total of 218,972 black farmers that owned or mortgaged their land rightfully, but one hundred years later that number had decreased to 30,000(9) with Texas having the most among the fifty states with a total of thirty-five principal black farmers(10).

In shifting from rural to urban life, black Texans found better-paying jobs that were less strenuous than farming, opportunities to pursue professions in liberal arts, and experienced the fight for equality in terms of voting and civil rights. That left Prairie View A&M facing a need to increase liberal art studies amid the inherent decline of black farmers in the state. The school’s original curriculum was designed by the Texas Legislature in 1879 to accommodate that of a “Normal School” to train teachers and was expanded to include the arts and sciences, home economics, agriculture, mechanical arts and nursing after the University was established as a branch of the Agricultural Experiment Station (Hatch Act, 1887) and as a Land-Grant College in 1890, beginning the tradition of agricultural research and community service.

In 1919, the school’s four-year senior college program began and in 1937, a division of graduate studies was added, offering master’s degrees in agricultural economics, rural education, agricultural education, school administration and supervision, and rural sociology(11).

1890 Land-Grant and Black Social Structures

From a historical context, it is essential to note that, during segregation, Prairie View A&M University served as not only a land-grant university but the hub for black education in Texas drawing students from the state’s all-black public schools via the Prairie View Interscholastic League which governed academic, athletic, and music competitions for those schools. Most of their state championship competitions were held at Prairie View. With that level of influence, Prairie View A&M was instrumental in the enlightenment and development of the black community statewide in terms of education, agriculture, athletics, and outreach. However, this advantage was dissolved in the late 1960s as public schools desegregated.

In the 19th century, the black community experienced a multitude of challenges from being displaced, fighting for civil rights, and the pursuit of happiness. The 1890 Land-Grant model plays keenly to W. E. B. DuBois’s “talented tenth” theory, which indicated that the college-educated 10 percent of the black community be charged with providing leadership during the post-Reconstruction era. It is also noted that the 10 percent have the responsibility to enlighten the other 90% of the black community through education, economic development, and mentorship. With this social concept in place, the development of the black class stratification began to formulate. The classes consisted of the upper, middle, and lowers classes, and terms were eventually developed to categorize one’s station such as the black proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Within the state of Texas, there was an influx of more black Americans earning tertiary degrees, which in turn created an increase in black Americans being thrust into the middle class attaining skilled jobs that previously were more common in northern urban communities.

Those who attained degrees from Prairie View A&M University returned home often to teach, preach, or open businesses, which also created jobs. This enlightenment introduced a new narrative for the black community that shied away from the harsh work of previous generations of sharecroppers and laborers.

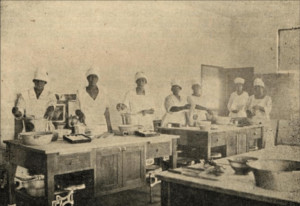

Female students in a domestic science class at PVAMU during the early 1900s. (Courtesy of PVAMU’s Special Collections and Archives Department)

Can Agriculture Reunite the Black Community?

Agriculture will forever be woven into the fabric of the Texas black community because, in some spiritual sense, we can associate with the history of the land that used to be working fields. Agriculture in the 21st century may not look the same from the 1800s or 1900s because there are new and innovative agricultural techniques that are being implemented in mostly urban areas such as aquaponics, urban gardens, and high tunnels. Utilizing these techniques, black communities, who often serve as case studies, can employ this trend of agriculture innovation to the black community’s advantage.

With the increasing numbers of black communities in urban areas beginning to engage in innovative small-scale agriculture such as community co-operatives and aquaponic farms, Texas’s only 1890 Land-Grant University can seize this opportunity, one that could consequently reconnect generations within the black community through agriculture and reshape historical relationships. Agriculture among black Texans will forever be linked by sweat, tears, and blood that our ancestors shed so that we could get to our current station in society as a people.

Agriculture was a major factor in the development of the black community and its cultural identity and was the primary earthly link that kept communities together. Our roots are in agriculture and it is now time to not turn our back on our roots, but to turn back to return to them as a community, and culture. This theory depends heavily on several factors. First, continuing the relationship with Prairie View A&M University, which has the wherewithal to devote manpower to these communities in terms of outreach and education. Second, working with entities such as the school’s Cooperative Extension Program to satisfy demands from the black community for such education. The last component of this trifecta is whether the culture can sustain the demand for agricultural activities in the black community and whether the community is willing to relinquish the past acrimonious relationship between slavery and agriculture.

Is this theory practical? Will Texas black communities revitalize agriculture with new practices? Will Texas experience an increase in a new generation of black farmers? Will Texas black communities rally around agriculture once again or do all of these questions constitute a pipe dream? I hope that it isn’t another one hundred and forty years before these questions and many more are answered.

Sources:

“(1890) Second Morrill Act.” BlackPast, 14 May 2019, www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/second-morrill-act-1890/.

B., Randolph. “Slavery.” The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), 15 June 2010, tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/yps01.

Castle, Emery N. “Christy, Ralph D., and Lionel Williamson, editors, A Century of Service: Land-Grant Colleges and Universities, 1890–1990. Transactions Publishers, 1992, XXV + 166 pp.,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74.3 (1992): 837-838

Chen, Adeline, and Teo Kermeliotis. “African Slave Traditions Live on in U.S.” CNN, Cable News Network, 25 May 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2012/12/07/us/african-slave-traditions-live-on-in-u-s/index.html

“College History.” PVAMU Home, 2010, https://www.pvamu.edu/about_pvamu/college-history/

“Deep Ellum in the 1920s.” Grave City, 19 Feb. 2017, gravecity.wordpress.com/2017/02/19/deep-ellum-in-the-1920s/.

Principals and Presidents. PVAMU Home, https://www.pvamu.edu/president/past-presidents/

Roberts, Andrea. “The Texas Freedom Colonies Project Atlas & Study,” (2018), http://www.thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com/p/atlas-study.html

“History and Overview of the Land Grant College System.” National Research Council. 1995. Colleges of Agriculture at the Land Grant Universities: A Profile. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/4980

Reid, D. A. (2003). “African Americans and land loss in Texas: Government duplicity and discrimination based on race and class.” Agricultural History, p258-292.

Robinson, Marco, and Phyllis Earles. “Engaging the Public with and Preserving the History of Texas’s First Public Historically Black University.” KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2018, doi:10.5334/kula.33.

Sanders, Brandee. “History’s Lost Black Towns.” The Root, The Root, 12 Jan. 2017, www.theroot.com/historys-lost-black-towns-1790868004.

USDA 2007 Census of Black Farmers, www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2007/Online_Highlights/Fact_Sheets/Demographics/black.pdf.

End Notes

- Denotes the initial exigency for the abolishment of slavery and the social consequence slaves were afforded post the American Civil War. (History and Overview of the Land Grant College System, 1995)

- Justin Morrill saw it fit that freedmen to receive the same liberties as their Anglo Counterparts in terms of education, liberation, and quality of life. ( History and Overview of the Land Grant College System, 1995)

- From a cultural context, many slaves remained rooted in their cultural rituals that incorporated some form of agriculture that symbolized masculinity such as fertility, strength, and endurance which were required to grow and protect families and tribes. (Chen, 2018)

- Post-Slavery prompted freedmen to establish themselves, which was typically done through establishing communities often unincorporated and properly documented in various parts of the county. Many of these colonies are either defunct, preserved, or recently rediscovered by researchers such as Dr. Andrea Roberts of the Freedom Colonies Project. (Roberts, 2018)

- The listed locations are post-slavery black settlements that are more prominent in the state of Texas. The colonies often consisted of close relatives, churches, farms, and homes. (Roberts, 2018)

- Due to the development of social barriers and limited resources, many colonies were displaced by Anglo-Americans settlements. (Sanders, 2017)

- It was common for freedmen to get lynched if they were to disobey often wealthier Anglo Americans during the migration of Anglo Americans to black colonies. (Randolph, 2010)

- Through many legislative sessions, there were changes to the university, but the common theme that remained a constant was the need and education in the science of agriculture to students and black communities in Texas. (Principals and Presidents, 2010).

- There was a considerable decline in the number of black farmers across the country for a number of reasons such as taxes, profitability, and legislation. (USDA Black Farmers, 2007).

- While the number of black farmers has decreased exponentially over the course of one hundred years Texas has the highest number of black farmers in the United States. (Reid, 2013)

- Prairie View sought to increase the competitiveness and capacity of farmers and students in the realm of agriculture and education which is why it was crucial to develop viable graduate programs. This move was also important to counter the fact that there was an increased degree of interest in agriculture-related careers such as farming and processing. (PVAMU History, 2010.)