The Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, though word of the edict would not officially reach Texas for another two and half years — June 19, 1865. This essay traces the road to the proclamation and also looks at how Texas was affected and why freedom for Texas slaves was so much longer in coming.

Video: View a PBS documentary about Juneteenth produced and directed by Jim Bailey, Sunset Productions, for the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture.

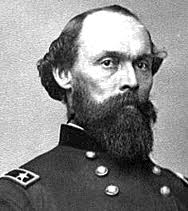

Frederick Douglass

The great abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass called the Emancipation Proclamation, “The nation’s apocalyptic regeneration,” and it’s doubtful that anyone today can fully appreciate the enormity of that moment or the rush of emotions for the four million black people who destruction of an institution that was an affront to humanity gave new life and hope to a long-suffering people in a land predicated on freedom and justice for all. The document itself, barely 700 words in length, carried moral, political, religious and military meanings and is revered as one of the most dynamic in world history and the man who brought it to be, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, is largely revered as the great emancipator – outside of the South.

However, having defiantly watched as their ways of life and economy forever changed, Southerners solidly laid blame on Lincoln and viewed the president in much less glowing terms. However, while Southerners were the most vocal about keeping transplanted Africans in bondage – for agricultural and social reasons, most citizens of the New World that would grow into the United States of America had begun cultivating attitudes about the slavery from the moment the first slave ships docked in this country in the Virginia Colony at Point Comfort, on the James River, late in August 1619. There, “20. and odd Negroes,” as the manifest read, from the English ship White Lion were sold in exchange for food and some (if not all) of the Africans were then transported to nearby Jamestown and sold.

And so began our sad relationship with the peculiar institution, as slavery has been called. The Virginians put Africans to work cultivating tobacco crops because of its similarity to farming methods Africans had developed in their home country, in this case probably Angola, in West Central Africa. As the colonies grew, so did the need for more field labor to grow the crop, but so too did the weight on the moral conscious of the burgeoning country begin to increase. The debate over human bondage vs. human rights in the name of the economy was a spirited one though the underlying and real debate was certainly about the value of one man’s existence and whether that man, because of his color, was inherently inferior in all matters, social, moral, and intellectual.

All men created equal?

Eli Whitney

The Declaration of Independence, on the issue of the black man’s rights was nebulous, at best, and would only supply more fodder for debate. Lincoln, then a rising Illinois Republican, would offer his interpretation in 1857, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in the Dred Scott decision (where Scott, an Illinois slave, was suing for his freedom). Said Lincoln: “The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity, but they did consider all men created equal – equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

So, while the Declaration of Independence may not have offered guidance on the issue of the black man’s rights, there was still a sense after the American Revolution that blacks would experience the ideals of independence and what the new country stood for, but that would not last very long as in 1793 Eli Whitney presented his cotton gin and almost overnight the Southern economy would begin to boom and replace tobacco as the burgeoning nation’s most profitable crop, and elevate the need for slavery.

Ten years after the gin (short for “engine”) first appears, the value of the total U.S. crop rose from $150,000 to more than $8 million. Combined with the developing textile industry in New England, cotton fuels the industrial revolution, and a marked rise in slave labor. The federal census of 1790 counted 697,897 slaves, but by 1810, that number increased 70 percent to 1.2 million slaves. However, at the same time, abolitionists had begun voicing the need to eliminate the institution, but other movements and sentiments thwarted any successful efforts to bring the end of slavery to fruition. For instance, the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act gave any white person the right to claim any black person, free or slave, as a fugitive, and return or sell that person into slavery.

Slavery: “A monstrous injustice”

Horace Greeley

There was never any real consideration by the majority of the country that a black man’s station was anything beyond that of a slave. Yet, during his presidential campaign in 1860, Lincoln was strongly supported by the abolitionist movement and their voices were growing stronger. They had cause for optimism by the time Lincoln took office in 1861 as the first Republican president and a candidate whose party platform had been anti-slavery. Lincoln had always thought slavery a “monstrous injustice,” however, he did not consider himself an abolitionist. His aim was to prevent the extension of slavery to new territories in the west though Southerners clearly saw Lincoln as a man on a mission to end slavery which, in turn, would destroy the Southern economy and social order.

For his election as president, the large majority of his winning votes came from the North and West, but in 10 of the 15 Southern slave states, there were no ballots cast for him, and he was victorious in only two of 996 counties in all the Southern states. In his inaugural address, on March 4, 1861, Lincoln re-iterated to skeptical Southerners, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” But, South Carolina had already become the first state to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860, quickly followed in January and February by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Virginia joined the Confederacy in April after the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter. In May, so did Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

Abolitionists increased their push for Lincoln to grant freedom to slaves but the president attempted a precarious balance, not wishing to incite the four remaining slave states who were still in the union – Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland, and on a wider scale he didn’t want to upset the general public who would not be sympathetic or supportive of a war perceived to be about slavery. In a letter to New York Tribune editor and abolitionist Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862, Lincoln wrote, in response to a Greeley editorial: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

With the country now raging with war, free blacks were eager to participate to help the push for emancipating their brothers in bondage, but also to show the black man’s patriotism, and bravery, which had been a similar theme since the American Revolution – in which the first casualty was a black man, Crispus Attucks, during the Boston Massacre. The notion was that military service would place blacks in a better light as citizens worthy of acceptance by whites and opening doors of opportunity and equal rights. A laudable theory, but wildly unsuccessful throughout history. Service, patriotism, heroism, civic duty, none of that mattered in the grand scheme of racial intolerance and did nothing to further the black man’s quest for civil and human rights.

A White man’s war!

David Tod

Still, as the Civil War begins, blacks in northern cities are literally begging to join the Union army and are soundly rejected at every turn. A group of black men in Boston passed a resolution (to no avail) seeking enlistment: “Our feelings urge us to say to our countrymen that we are ready to stand by and defend our government as the equals of its white defenders; to do so with our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor, for the sake of freedom, and as good citizens; and we ask you to modify your laws, that we may enlist, that full scope may be given to the patriotic feelings burning in the colored man’s breast.” In September 1862, black volunteers in Cincinnati sought to join the Army through the formation of local units called “Home Guards,” only to incur the wrath of the city’s police chief, who told them: “We want you damn niggers to keep out of this; this is a white man’s war!” If the chief’s statement was in any way unclear, Ohio Governor David Tod later amplified: “Do you know that this is a white man’s government, that the white men are able to defend and protect it, and that to enlist a Negro soldier would be to drive every white man out of the service?”

The perceived purpose of the war was to quell the rebellion and pull the Southern states back into the Union, no matter their reasons for secession, but unspoken was the powder keg of intentions of emancipation through waging war, and in no parts of the country did whites want to hear that was what the war was about. Yet, it was, regardless how painful the reality was for non-abolitionists in the North, and what state’s rights Southerners really fought for was the right to hold slaves to perpetuate the cotton economy. The war WAS about emancipation, or as some historians have called it, “the War of Treason in Defense of Slavery.”

And Lincoln would say as much in his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865: “One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.” So, there is a Catch-22, where White non-abolitionists in the north have no intention of enlisting to fight in a war whose objective was emancipation for the “undeserving” Negro, especially when the Negro himself was not fighting – or allowed to fight. There was also the feeling, given the notion of inferiority, that Negroes were not worthy of wearing the uniform, and giving them arms was totally out of the question. And, perhaps above all, many whites feared that emancipation encouraged the most detested of all the social taboos: miscegenation, race-mixing.

Black men in uniform

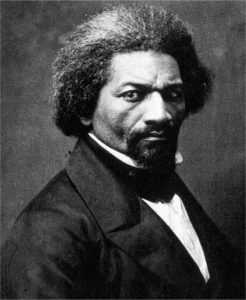

Sgt. William Carney

In another paradox, whites in the North were increasingly competing with freed blacks for jobs which sometimes led to unemployed whites getting drafted to the Army after being displaced on their jobs by Negroes and then being sent off to fight in a war to set more Negroes free. Yet, the Union does make attempts to enlist free blacks and slaves in Union loyal states. In 1863, there was a program in which slave owners could receive up to $300 for each slave allowed to enlist in the Army. But there was also confusion within the government’s ranks in how best to treat slaves who escaped to safety behind Union lines. There was no official policy on what to do with them. Some Union officers declared them “contraband of war,” given they had been aiding the Confederacy by working to build fortifications and holding other jobs in support of the Confederate Army. Other Union officers saw that runaway slaves were returned to their masters. By the end of the war, an estimated 500,000 slaves had successfully found their way to freedom behind Union lines.

The solution was the First Confiscation Act on August 6, 1861 which provided, basically, that any captured slaves who had been working for the Confederate Army were to be “forever free.” The Second confiscation Act, July 17, 1862, freed all rebel-owned slaves who escaped behind Union lines. On that same date, the Militia Act freed all slaves in Union Army employ. Blacks eventually would serve in large numbers after emancipation, and in many cases would prove to be valiant in battle, as “colored troops,” most notably the 53rd Mass., the subjects of the film “Glory,” for their courageous performance at Fort Wagner. Their participation in that battle produced Sgt. William Carney, the first African American to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. Over two hundred members of the 62nd United States Colored Infantry (recruited from Missouri in 1863) fought in the Battle of Palmito Ranch on May 12-13, 1865 in South Texas, which is noted as the last skirmish of the Civil War.

Approximately 180,000 African Americans comprising 163 units served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more served in the Union Navy. Both free blacks and runaway slaves joined the fight and African American soldiers would participate in every major campaign of 1864-1865 except Sherman’s invasion of Georgia. On July 17, 1863, at Honey Springs, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), the 1st Kansas Colored fought with courage commanded by Gen. James Blunt when they ran into a strong Confederate force under Gen. Douglas Cooper. After a two-hour bloody engagement, Cooper’s soldiers retreated. The 1st Kansas, which had held the center of the Union line, advanced to within fifty paces of the Confederate line and exchanged fire for some twenty minutes until the Confederates broke and ran. Blunt wrote after the battle, “I never saw such fighting as was done by the Negro regiment….The question that Negroes will fight is settled; besides they make better solders in every respect than any troops I have ever had under my command.”

Back to Africa?

There were two other key movements towards emancipation:

- April 1862 – congress outlaws slavery in D.C. and the Western territories. It’s interesting, though, that in doing so Lincoln also recommended colonization for the freed slaves with the government providing $100,000 for the voluntary emigration of freedmen to Haiti and Liberia. And in August of that year, he met with a group of prominent Negroes at the White House seeking their support for colonization, telling them: “Your race suffer greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason why we should be separated.” Some South American and African governments were approached about the idea. While nothing became of colonization, Lincoln never fully gave up on the idea of sending freed slaves back to Africa and other countries, but there is no mention of colonization in the Emancipation Proclamation.

- On June 19, 1862, Lincoln signs a bill abolishing slavery in the western territories and on July 17, and a measure becomes law setting free all slaves coming from disloyal masters into Union-held territory.

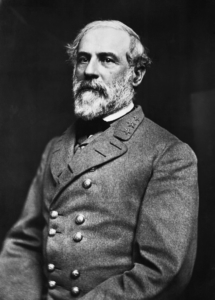

Gen. Robert E. Lee

Lincoln’s piecemeal approach to ending slavery was having success, but Constitutional restraints prohibited him from making emancipation a reality on a wider scale. However, as commander in chief of the Army, he could circumvent the Constitution and end slavery for military reasons. The Confederate Army used slaves in support roles for the rebel cause, including maintaining operations at plantations and farms while their masters are away for the fight. Granting freedom to slaves in the South would greatly weaken the Confederate war effort. Indeed, the South will be doomed. On September 17, 1862, Union and Confederate soldiers fight what will be the bloodiest batter in American combat history with over 23,000 casualties on both sides. Antietam was Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s first foray into Union territory, a risky gamble that did not pay off. Lee withdrew from the area the following morning, and it’s the moment Lincoln and his Cabinet have been awaiting. Not wanting to appear desperate beforehand, they had been seeking a decisive battlefield victory to bolster the president’s emancipation announcement.

Free at last…somewhat

In reality, it was a thinly veiled Union victory heightened by Lee’s retreat after the exhaustive battle that left both sides severely battered, but that was enough for Lincoln. Five days after the Antietam fight, he issued his preliminary proclamation announcing his intention to free slaves in rebellious states on Jan. 1 unless the Confederate states rejoin the union. Only abolitionists are excited by the move. The Confederate States stand fast. In anticipation of emancipation finally becoming a reality, on December 31 there are watch meetings in several Northern cities held by Negroes and whites attended by abolitionists such as Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. On Jan. 1, the proclamation frees three-fourths of the slaves – all in the Confederacy, where slave owners ignored Lincoln’s “act of justice warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity.”

Still, there are 800,000 slaves unaffected in the four loyal slave states, 13 parishes in Louisiana, including New Orleans, 48 counties in Virginia (which had become West Virginia), and seven counties in eastern Virginia, including Norfolk and Portsmouth. Today, when the president signs a major piece of legislation, there are dozens of interested parties standing around his desk and receiving ceremonial pens and taking photos. However, Lincoln unceremoniously signs one of the most incredible documents in history in the presence of less than a dozen people, as he juggled the signing with appearing downstairs at a New Year’s Day reception at the executive mansion. And, apparently, he had shaken so many hands at the reception that he had difficulty holding the pen to sign the document. The gravity of the moment, however, and his legacy was very clear to the president, who would say: “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper,” he declared. “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

As word of the proclamation filtered down to slaves, the security of whites in the South and maintenance of its stable economy became major issues. The Confederate war effort could not proceed successfully without slave labor, in the battlefields or the cotton fields and other farms. And as slaves gradually became aware of their freedom, well, the picture of slavery took a dramatic new image. Between 1861 and 1965, slaves walked off plantations and away from bondage whenever Union troops were near. Slave owners attempted to refugee their slaves, or “run the Negroes,” removing them away from Union lines, hiding them from federal troops – which is how many slaves first came to Texas (perhaps as many as 50,000, maybe as much as three times that many AFTER the proclamation) from other Southern states.

Texas was a safe haven for slaveholders because of the limited Union presence in the state. There were no major Civil War battles in Texas so no opportunities for slaves to seek shelter behind Union lines. Slavery in Texas during the war was relatively unaffected and with that knowledge slaveholders moved their slaves to Texas and re-established their plantations. Some freedmen seized the opportunity to turn on their masters. One Mississippi citizen wrote for state assistance in keeping blacks in line: “There is greatly needed in this county a company of mounted rangers…to keep the Negroes in awe, who are getting quite impudent. Our proximity to the enemy has had a perceptible influence on them.” In another case, a slave learned that he was free and “went straightly to his master’s chamber, dressed in his best clothes, put on his best watch and chain, took his stick, and returning to the parlor where his master was, insolently informed him that he might for the future to drive his own coach.” Others simply refused to work or accept punishment and whites, in some cases, even appealed to Union troops for protection from former slaves.

Enlisting slaves for the Confederate Army

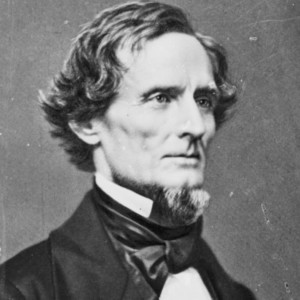

Jefferson Davis

The Confederacy relied on slave labor to do the non-combat work of the war as cooks, teamsters, mechanics, hospital attendants. Yet, when inevitably pressed for manpower, Confederate leaders debated the idea of enlisting slaves for the Southern cause near the Civil War’s end with Union troops marching through the South claiming victory after victory. Eventually, there were some blacks who wore the uniform of the Confederacy, but the widely accepted opinion on their exclusion from donning the battle gray uniforms was as Confederate General Clement H. Stevens stated in reference to the recruitment of slaves for the preservation of Dixie: “I do not want independence if it is to be won by the help of the Negro…The justification of slavery in the South is the inferiority of the Negro. If we make him a soldier we concede the whole question.”

In March 1865, with the tide turned decidedly in favor of the North, Confederate President Jefferson Davis approved the enlistment of 300,000 slaves, with the predictable promise of freedom, but their addition came much too late to help Johnny Reb. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, but it would not be until August 20, 1866 that President Andrew Johnson would officially declare the war over. With the South crushed and Reconstruction underway, states ratified, in short order, the 13th Amendment (December 6, 1865), which outlawed slavery, the 14th Amendment (July 9, 1868), granting citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included former slaves, and the 15th Amendment (February 3, 1870), which gave the right to vote to former slaves.

Slavery and the Lone Star State

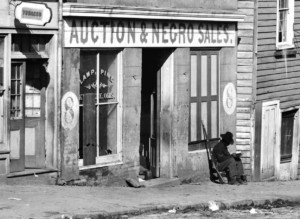

Slave auction house

Where is Texas in all of this? Texas was readmitted to the Union on March 30, 1870. However, since there were no major battles during the war in Texas, slave life in the state continued relatively unaffected, other than the influx of “refugee” slaves. Slave owners and male family members did venture off to fight for the Confederacy, leaving, in some cases, male slaves in charge of running plantations and farms. It’s possible that some of the refugees may have brought news to Texas slaves about emancipation, but with no real Union presence in the state, there were no opportunities for slaves to bolt to freedom. Union forces never made it to the state’s interior, where there were approximately 200,000 enslaved people when the war began. Galveston was occupied briefly in the fall of 1862, but on New Year’s Day, 1863, the very day when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, Confederate forces led by General John Bankhead Magruder recaptured the port.

Later Union attempts to occupy Texas were either limited to the state’s southern coastline, far away from the East Texas counties with the densest slave populations, or they were turned back before they even reached Texas. Only 30 percent of Texas families owned slaves in 1850, and only 2 percent of those held 20 or more slaves. However, Texans had not only fully grasped slaver-owning concepts, but were downright giddy about the future prospects of slaves cultivating the state’s fertile soil, especially its cotton crop. In the late 1850s, an editorial in Austin’s Texas State Gazette suggested that “until we reach somewhere in the vicinity of two millions of slaves, it is evident that such a thing as too many slaves in Texas is an absurdity.” Charles DeMorse of the Clarksville Northern Standard was more direct: “We want more slaves, we need them.”

In 1860, Texas was the 5th-largest cotton-producing state in the country, with 90 percent of the state’s produced by farmers or plantation owners who owned slaves. In 1865, a resolution emerged from a public meeting in Goliad that “the discussion of the question, whether it is expedient or politic to abolish southern slavery, is premature, unwise and unnecessary, and impressed the Northern mind with the belief that we feel unable to sustain the institution…(slavery) is not to be wrested from us by any power on earth.” It should be noted that it was in Goliad where the first battle of the Texas Revolution occurred in 1835 and the first casualty of that conflict – and, thus, the Revolution – was a free black man, Samuel McCullough. Yet, the war certainly had a toll on Texas. The ripple effect of the Southern economy’s failing reached Texas and many of its Confederate soldiers returned to their farms to find devastation and there was no cash to be had for rebuilding. But, in the early months of 1865, Texas newspapers still contained advertisements of slaves for sale as Texans went about their slave-holding business as usual openly defying compliance with the proclamation.

Some Texas slaves reported being in bondage as much as six years after emancipation, and after Juneteenth, blacks were murdered, lynched, and harassed by whites. “The war may not have brought a great deal of bloodshed to Texas,” notes North Texas University historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner, “but the peace certainly did.” Slave “patrols” of whites scoured the countryside for runaway blacks, who were beaten and sometimes killed. The same held true for sympathizing whites.

The fear and uncertainty about emancipated slaves was evidenced in stories appearing in the Galveston newspaper, wondering about the white citizens’ plight, economically and socially, under “a government in which we have now no voice.” Another piece, in the Galveston Tri-Weekly News, on June 21: “This attempt to overthrow an institution that has become a part of our social system and which our entire population has believed essential to the welfare of both races, led to the war … and all we can do in our present entire dependence on the clemency of our conquerors, is to repeat to them what we have been urging for so many years … that the attempt to set the negro free from all restraint and make him politically the equal of the white man, will be most disastrous to the whole country and absolutely ruinous to the South.”

That was the mood that greeted Gen. Granger and his troops, who met no resistance at Galveston, two and a half months after Lee’s surrender and three weeks after Gen. E. Kirby Smith had surrendered the last regular Texas Confederate soldiers at Galveston Island. Granger was sent to command the Department of Texas and among his first duties was announcing General Order No. 3: “The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor: The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” Granger set up a provisional government as some of his troops continued throughout South and East Texas enforcing the “official” mandate of freedom.

Why had it taken so long for the word about emancipation to reach this state? There are varying accounts, some myths, of why the news was delayed in getting to Texas. Take your pick:

- A messenger was murdered on his way to Texas.

- The news was deliberately withheld by enslavers to maintain the labor force on the plantations.

- Federal troops actually waited for the slave owners to reap the benefits of one last cotton harvest before going to Texas to enforce the proclamation.

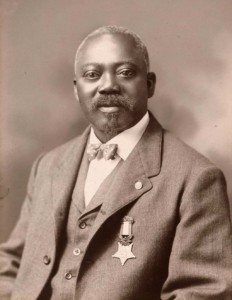

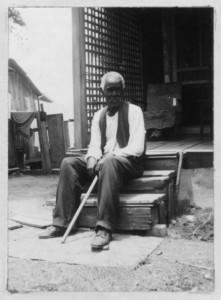

Felix Haywood

Whatever the reason – most likely the lack of Union troops in Texas during the war – it didn’t seem to matter. Freedom had come to Texas slaves. Granger’s announcement triggered shockwaves of joy, fear, and confusion throughout the area. Blacks were happy, Whites were scared, and large segments of both groups generally had no idea what to make of the situation. One former slave, Felix Haywood offered this insight in the Slave Narratives. “Everybody went wild. We all felt like heroes … just like that we were free. It didn’t seem to make the whites mad, either. They went right on giving us food just the same. Nobody took our homes, but right off colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get close to freedom … like it was a place or a city. We knew freedom was on us, but we didn’t know what was to come with it. We thought we were going to get rich like the white folks. We thought we were going to be richer than the white folks, because we were stronger and knew how to work, and the whites didn’t, and we didn’t have to work for them anymore. But it didn’t turn out that way. We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud but it didn’t make them rich.”

Here is what some others said through the Slave Narratives:

- “When my oldest brother heard we were free, he gave a shoop, ran, and jumped a high fence, and told mammy good-bye. Then he grabbed me up and hugged and kissed me and said, `Brother is gone, don’t expect you’ll ever see me any more.’ I don’t know where he went, but I never did see him again.”

- “I remember that surrender day. He called us round him. I can see him now, like I watch him come to the yard with his hands clasped behind him and his head lowered. He said, `I love every one of you. You’ve been faithful, but I have to give you up. I hate to do it, not because I don’t want to free you but because I don’t want to lose you all.’ We saw the tears in his eyes.”

- “When the news came in that we were free, Master Harry never called us like everybody else did their slaves; we had to go up and ask him about it. He came out on the front gallery and said we were free and turned around and went in the house without another word.”

- “Us niggers was set free on June 19, 1865. We was told dat we was goin’ to git sixty acres and a mule. We never git nothin’ lak dat.”

- “The niggers bellered and cried and didn’t want to leave massa. He talked to us and said as long as he lived we’d be card for, and we were. … He willed every last one of his slaves something. … My mammy got two cows and a pair of horses and a wagon and 70 acres of land.”

- “Before the war massa didn’t ever say much about slavery, but when he heard we were free, he cussed and said, `God never did intend to free niggers,’ and he cussed til he died. But he didn’t tell us we were free til a whole year after we were.”

- Where Douglass had seen emancipation as a positive apocalypse, at least one slave owner had a very different vision: “Missy found Marster Billy dead in the shed, with his throat cut and the razor beside him. There was a piece of paper saying he did not care to live because the niggers were free.”

The Galveston Daily News, on June 21, 1865, saw it like this: “Their freedom can never make them the equals of the white race. … God himself has made a marked distinction between the white and black races, which no human laws, nor all the abolitionists in the world, can ever obliterate.” In 1979, Gov. Bill Clements signed a bill making June 19 “Emancipation Day in Texas,’” a legal holiday. Emancipation for Blacks in Texas, for former slaves throughout the Union, no matter how awkward its first steps, would defy even the most dire predictions for what was to become of a race of people suddenly given the ability to decide their own direction and overcome such notions as this one: “The extinction of slavery is simply the extinction of the Negro race.”

Sources:

- Franklin, John Hope, “From Slavery to Freedom, A History of Negro Americans,” Third Edition, New York: Vintage Books, 1969.

- Williams, David A., “Bricks Without Straw, A Comprehensive History of African Americans in Texas,” Austin: Eakin Press, 1997

- Marten, James, “Slaves and Rebels – The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1861-65,” p. 40-48, in “Blacks in East Texas History,” Edited by

- Bruce A. Glasrud & Archie P. McDonald. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008.

- Barr, Alwyn, “Black Texans, A History of Negroes In Texas, 1528-1971,” Austin: Jenkins Publishing Co., 1973

- Campbell, Randolph B., “An Empire for Slavery, The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821-1865,” Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989

- Austin American-Statesman, “Slaves’ emancipation came a little later to Texas,“ Michael Hurd, June 19, 1995, p. A1

Online:

- http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured_documents/emancipation_proclamation/

- http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/EmanProc.html

- http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/almintr.html

- http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h1549.html

- http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/emancipation-150/10-facts.html

- http://www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org/inside.asp?ID=69&subjectID=4

- http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres32.html

- http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/inaug2.htm

- http://www.ehow.com/about_4567222_slave-owners-texas.html#ixzz24UelCepH

- http://theragblog.blogspot.com/2011/10/bob-feldman-slave-state-of-texas-1846.html

- http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qdc02

- http://www.tbhpp.org/emancipation.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipation_Proclamation

- http://www.history.com/topics/emancipation-proclamation

- http://www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org/inside.asp?ID=39&subjectID=3

- http://wcm1.web.rice.edu/before-juneteenth-talk.html#fn6

- http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ewyatt/_borders/Texas%20Slave%20Narratives/Texas%20Index.html