“Austin’s L.C. Anderson High School as an Equalization School: 1953-1971”

Rebekah Dobrasko

Historic preservation specialist and lead historian at the Texas Department of Transportation

Austin

Abstract

In the 1950s, states, municipalities, and school districts across the southern United States scrambled to construct new African American schools in order to prove they truly provided “separate but equal” segregated schools. African American public education had long been neglected in the South in favor of funding white schools, but as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Black students began winning cases in the courts for equalization or desegregation, Southern politicians finally turned their attention to equalizing primary and secondary public school systems. In 1950, Austin, Texas had one white high school (Austin High) and one Black high school (L.C. Anderson High). In order to keep the schools segregated, Austin school officials, in 1953, sought to “equalize” Anderson with a new, modern building that had more classrooms, science laboratory space, an updated heating system, and athletic fields during the middle of school equalization and desegregation lawsuits. However, the Austin Public School system desegregated under a “freedom of choice” plan in 1955, and Black students began attending formerly all-white schools. Today, the building sits on a hill in East Austin as a physical example of the city’s efforts to equalize its segregated school system. Ultimately that effort failed, and a strong African American community center was lost to continued discrimination when attempting school system integration.

L.C. Anderson High School’s beginnings

African American public school education in the South has roots in the Freedmen’s Bureau established after the Civil War to educate millions of former slaves. Despite a brief experiment with integrated schools during Reconstruction and the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision, the vast majority of southern schools remained segregated by race until the 1970s. The African American schools served as centers of their community, provided employment and leadership opportunities for Black citizens, and showcased pride in Black student achievements. Institutional racism as practiced by white politicians and school board members meant that Black schools always received the least amount of funding and were often the first to close to achieve a measure of racial integration. Only under threat of desegregation lawsuits did the white power structure of the South ever invest money in its public school system.

L.C. Anderson High School in Austin, Texas, serves as a case study for community cohesion and pride in the face of institutional racism. Austin’s only Black high school is rooted in the 1880s. While the school continually suffered from unequal funding and investment, it was upgraded in 1953 in an attempt to forestall any desegregation lawsuits in Austin. This new school building provided amenities like a gymnasium, athletic fields, and specialized classrooms for the first time, but quickly became overcrowded. Ultimately, the new Anderson High School was only open less than 20 years, as the Austin Independent School District (AISD) chose to close the high school in 1971 and bus its students to local white high schools to attain integration. Similar erasures of long-standing African American institutions occurred across the South. Anderson’s closure irreparably damaged the African American community, as businesses closed and Black families moved closer to their new schools. Alumni of the original L.C. Anderson High School are proud of their school and achievements, but continue to be bitter about the school’s closure.

Austin has a long tradition of segregated African American public schools. Early education began in some of Austin’s freedmen communities scattered across the new capital city. Austin area Black educators founded schools in the 1870s and 1880s in the freedom colonies of Robertson Hill, Clarksville, Masontown, and Gregorytown. Austin’s first African American high school opened in 1889 in Robertson Hill, on the corner of San Marcos Street and East 11th Street. High enrollment quickly caused overcrowding, and a new, two-story frame school opened in the early 1900s on Olive Street.

The Olive Street school was small and not suitable as a public high school, so the Austin Public School (APS, the predecessor to AISD) system built a new, larger brick high school nearby on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Comal Streets. This school opened in 1913 as E.H. Anderson High School, named after Prairie View Normal School’s first Black president. His brother, L.C. (Laurine Cecil) Anderson, was principal of Austin’s Black high school from 1896 through 1928, and upon his death, the school was renamed L.C. Anderson High School(1).

Austin’s public African American schools were always located in East Austin (east of East Avenue, now Interstate 35 that runs through the city). In 1928, an Austin City Plan recommended public Black schools only be constructed in East Austin as part of the city’s “Negro District.” The city plan’s authors, Dallas/Forth Worth-area urban planning and consulting firm Koch and Fowler, chose east Austin as the Negro District in part because of the presence of Anderson High School. This government-sanctioned racial segregation led most of Austin’s Black families to move east to be closer to public schools, and later a Black public library, swimming pool, and park(2).

Austin’s African American students lived, played, and learned within this segregated “Negro District.” They attended school together, first at Blackshear Elementary School, then to Kealing Junior High School, culminating with a high school education at Anderson. Families attended Anderson band concerts at the segregated African American Rosewood Park. There was a growing Black business district in East Austin, and students, parents, and teachers often attended church together(3).

East Austin also served the wider African American community surrounding the city. Small rural schools educated the children that grew up on farms, but those schools typically only went until seventh grade. If students wanted higher education, they had to attend Anderson. To do that, students from rural Travis County (or Hays County, 15 miles away) either boarded with family members or friends in East Austin, or traveled to the school on a daily basis(4).

During this time, fifteen states required racial segregation in their public schools. By the 1940s, African Americans across the south began to challenge this system. Long buoyed by the “separate but equal” doctrine as defined in an 1896 court case Plessy v Ferguson that allowed segregation as long as facilities were equal, African Americans began to challenge the fact that Black facilities were never equal to white facilities. Spurred by the treatment Black veterans received when they returned home from World War II, African Americans began organizing and demanding change(5).

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led the movement to overturn the doctrine, finding that in many states there were no African American equivalents for public graduate or professional schools, much less one that was “separate but equal.” In Texas, there were no public African American graduate, medical, or law schools. There was barely an African American public university. The Texas legislature established a public school to train African American teachers in 1876 on a former plantation in Prairie View, forty miles northwest of Houston. This school received additional federal funds through the federal Morrill Act of 1890 which gave money to agricultural and mechanical colleges regardless of race. Texas begrudgingly began funding the school at Prairie View with 25 percent of their Morrill Act funds. The school limped along, educating Black teachers and later developing a larger curriculum for bachelors’ degrees. However, any African American Texans interested in graduate school or professional school would have to leave the state in order to pursue further education(6).

Houston post office employee Heman Marion Sweatt, with the backing of the NAACP, sought to change that and, in 1946, sued the University of Texas at Austin (UT) for admission to its law school. Instead of breaking the color line and admitting Sweatt to UT, Texas lawmakers scrambled to put together a separate law school for Sweatt to attend. They also began pouring state money into the facilities at Prairie View and began construction on the Texas State University for Negroes in Houston. Carter Wesley, a Black newspaper publisher in Houston, stated that “we have got to file suits for equalization of educational opportunities if we expect our children to get the benefit of improved education in our time”(7).

While the NAACP sued various state universities over the lack of professional and graduate degree programs, calls for improving African American schools at the primary and secondary level grew across the South. In Austin, at multiple school board meetings, the Negro Citizens Committee pressured Austin Public Schools to improve Black education. The committee demanded improvements to Anderson High School and asked that Black history be taught in the schools. The committee also requested that Black supervisors manage Black teachers, providing additional leadership opportunities for Black professionals(8). African American parents and leaders made similar demands to school districts across the South.

The Rise of Equalization Schools

As courts began ordering states to provide equal facilities or admit Black students, state governments and school districts scrambled to build schools that were “separate but equal” to white schools. After decades of neglect and disinvestment in Black education, these shiny new “equalization schools” were a last-ditch effort to prevent being required by the courts to desegregate schools. Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina developed an elaborate system of state sales taxes and government oversight to build thousands of new schools for Black students (Dobrasko 2005). Virginia appropriated millions of dollars in the state budget to build new Black schools. Other states, like Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas did not have statewide equalization programs, but local school districts scrambled to equalize their schools. All school districts were concerned about keeping Black parents to challenge the racial status quo. As one student noted, “one of the things was to try and be sure that we were satisfied” with segregated schools(9).

Austin Public School officials watched as Texas attempted to open a law school at Prairie View A&M, heard the complaints from the Negro Citizens Committee, and recognized that L.C. Anderson High School was materially unequal to the white Austin High school. A 1948 study commissioned by APS found that the 1913 Anderson High School building was old and overcrowded. It was the only school remaining in the school district to use coal for heating. Some upper floors did not have bathrooms. Classrooms needed improved lighting and access to electrical outlets. Science classrooms did not have permanent equipment. Students in home economics classes practiced sewing on discarded aprons from the white high school. The cafeteria could not feed all the students and was “a slight jump ahead of being unsanitary.” The athletic fields were about 10 blocks away from campus, and the school had no gymnasium(10).

In addition to the demands swirling around equalization and desegregation, Austin’s population was growing quickly and schools became overcrowded. The post-World-War-II baby boom, as well as the urbanization of Texas, led growing families to move into Austin for work as men returned from fighting and began to settle down. However, Austin still segregated services for its African American residents in East Austin. The only Black junior high and high school in the city was located there and even if African Americans chose to move elsewhere in the city, they still needed to send their children to schools on the east side of town.

Despite the glaring inequalities between Anderson and the white schools in Austin, African American parents, teachers, leaders, and alumni treasured the time spent at the school. In oral interviews collected online, alumni recalled how the school and teachers helped them grow into productive citizens and helped them learn. Since every Black student in Austin had to attend one high school, students formed bonds with each other that served them well into adulthood. Because the majority of the students lived near Anderson High School, parents and students had easy access to the school, teachers, and any community events held at the school(11). However, as the African American community continued to grow in Austin, especially after World War II, Anderson desperately needed an upgrade.

A new “original” Anderson High School

In 1950, APS planned a massive school construction campaign to address the need for additional new white high schools as well as a new Black high school to encompass all the children coming up through elementary and junior high schools. The district passed a $10 million building bond for two new white high schools and improvement of other white schools in addition to a new Anderson High School and rehabilitation of the old Anderson into a new junior high for Blacks(12).

Plans for the new Anderson High School included purchasing a 21-acre site in East Austin, just off Rosewood Avenue. In directions to bidders for the design of the school, APS asked that the new school be limited to only two stories, with one-story wings as “desirable.” The roofs would be flat, with no parapet. The exterior would consist of brick masonry, with the interior having smooth masonry walls. APS found a combination of metal casement and glass block windows as “considered desirable” and noted that wood was not to be used in windows. The school plant must also have a steam heating system, hot water, and regular drinking fountains(13).

On the new campus, there would be eight regular classrooms, with the following specialized classrooms: art, typing, accounting, general business, home economics, woodworking, metalworking, drafting, vocational agricultural, music, physics, chemistry, and speech. The new school would have a cafeteria to seat a minimum of 225 people along with a stage, a library with a classroom, and a gymnasium/auditorium combination with another stage and locker rooms. To support student life, APS called for a student lounge, with space for social activities as well as a room for yearbook and newspaper publications. Over two thousand square feet of office space was necessary to allow for offices, a conference room, workroom, and teachers’ lounge(14).

For the first time, L.C. Anderson High School had its own dedicated recreational facilities, which drew the community into the school. Black Austinites cheered for the football team, track, basketball, and the award-winning band at football games on the new field. The gymnasium held pageants, dinners, graduations, and other community events. However, the new school was not enough, and APS needed to add six new classrooms in 1959, as well as equipment such as desks, science lab equipment, and books for the library (15).

The new Anderson opened in 1953 and schools similar in design sprang up across the South. These schools, like Anderson, followed modern architectural design principles for education. Post-World War II, new schools were one or two stories, for easy evacuation in case of a fire, had flat roofs, banks of aluminum-framed windows, and glass block windows meant to diffuse light in a classroom. The classrooms opened on to a courtyard and outdoor spaces. Because steel was still at a premium directly after the war, new schools used concrete block for construction and put brick veneer on the exterior. For African American schools, these new buildings often held the community’s first school with indoor plumbing, water fountains, cafeterias, and libraries(16).

Characteristics of post-World War II schools include flat roofs, brick veneer over concrete block, aluminum and glass block windows, and classrooms centered around courtyards. (Credit: Rebekah Dobrasko, 2018)

These modern new schools were certainly an upgrade from the smaller, overcrowded, and unmaintained earlier African American schools. The new schools were meant to provide “separate but equal” facilities but could not overcome decades of inequalities. Even though school districts built new Black schools, they often did not provide for the finishing or equipping of those schools. Photographs of the new Anderson High School in 1955 show students attending class in rooms with no wall or ceiling finishes. Students did not have desks and still read used books in their new libraries. Schools quickly became overcrowded again(17). The inequalities persisted. However, students, teachers, and parents remained proud of their schools and often praised the new school’s amenities and features.

While Southern school districts spent millions of dollars for the first time on attempting equalization of Black school facilities, the NAACP continued to sue states and school districts on the lack of equalization and demands for desegregation. The first primary school case to call for desegregation instead of equalization came from rural South Carolina in 1951. The Briggs v. Elliott case ultimately made its way to the United States Supreme Court with four other desegregation lawsuits from Virginia, Delaware, Kansas, and Washington, DC(18).

The Supreme Court consolidated the cases and handed down its landmark decision, known collectively as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in 1954. Reactions to the ruling varied across the South and across Texas. Some school districts, especially in west Texas and in borderline Southern states like Kansas, desegregated right away and opened integrated schools in the fall of 1954. However, most school districts declared their schools would remain firmly segregated and decided to wait for an order from the court that would indicate how to implement its ruling. In 1955, the Supreme Court stated that desegregation should proceed “with all deliberate speed”(19).

In Texas, many school districts chose to remain firmly segregated and planned to “study” the issue. The state NAACP and Black parents and students, especially in places like east Texas, demanded full compliance with the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Texas governor R. Allan Shivers stated desegregation in Texas would “take a long time”(20). While school districts like Houston remained segregated after 1955, the Austin Public School board decided to allow a “freedom of choice” plan for desegregation. For the 1955-1956 school year, only high school students could choose where to attend a public school. Eight Anderson High School students chose to desegregate the all-white schools of Austin High, McCallum High, and Travis High. One student attended McCallum High School because she lived in the Black neighborhood of St. John’s, which was much closer to McCallum than Anderson(21).

More African American students attended formerly all-white schools in 1956 when 20 Anderson students chose to enroll in one of Austin’s three white high schools. Throughout the 1950s and the 1960s, Austin’s public school system remained effectively segregated. It was not until 1963 that Austin’s “freedom of choice” plan included elementary schools. At that time, only ten percent of Black students attended previously all-white schools. Only eight white students attended formerly all-Black elementary schools. Anderson High School, however, remained all Black. Austin Public Schools, now reorganized as the Austin Independent School District (AISD) decided to take the next step and desegregate school faculties in 1964. The district superintendent assigned three Black teachers to white schools, although the chosen schools, Johnston High School and Allan Junior High School, predominately served Mexican American students(22).

Austin’s failing grade for integration

While the school district touted its integration of schools, not much changed, especially at Anderson. With the exception of a few students and teachers, Austin’s Black students still attended school at the Black high school.

As school districts across the South fought desegregation lawsuits, there were vicious responses to Black students attending white schools and the withdrawal of white students into private “segregation academies.” However, AISD continued its system of token desegregation. By the end of the 1960s, the federal government tired of school districts barely complying, if at all, with the Supreme Court order(23).

In 1968, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Office of Civil Rights reviewed 96 school districts across Texas, examining the districts for compliance with desegregation orders and requirements and found AISD maintained substantially segregated schools, especially among the traditionally African American schools. The district’s “freedom of choice” desegregation plan was not working. In 1968, Anderson remained all Black, and the district allowed all African American students, regardless of where they lived in the city, to transfer in and attend the school(24). That led HEW to give AISD a chance to develop a different desegregation plan.

In the next year, AISD attempted to integrate Anderson by redrawing its attendance zones, but only 17 white students transferred to the school. The school district refused to consider busing Black students to white schools because of parental objection to busing. Prior to redrawing the attendance zones, AISD scrambled to improve the 16-year-old school. The science labs received new equipment, the school was repainted, and the district committed to a “broader and stronger curriculum” in order to bring the school up to white parents’ and students’ expectations(25). The first attempts at desegregating Anderson went smoothly. One African American student stated, “We’ve always been open to integration, but no one ever wanted to come”(26). However, 17 students were not enough to show HEW that Anderson was integrated.

Over the summer of 1969, AISD proposed closing Anderson High School, along with all-Black Kealing Junior High and St. Johns Elementary, in order to achieve integration. The students would then be bused to other schools across the city. Based on Black community protests, the school board decided not to implement this plan, however, AISD decided instead to assign new white teachers to Anderson to continue integrating its faculty(27). Because AISD integration was not working, HEW filed charges against the district in January 1970, accusing AISD of being out of compliance with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and noted that the school district was “infected by a discriminatory environment,” and recommended withdrawal of all federal education funds from AISD(28).

No longer allowed “freedom of choice,” the court order drew new attendance zones for the 1970-1971 school year and required all students within those zones to attend their local schools. Reaction was swift, as parents raised the threat of legal action against AISD and promised to withdraw their children from public schools. Highlighting the continued inequality between Black and white education in Austin, one resident stated her children would “not receive the standard of education…in a school with a majority of Black students”(29). Over 300 white students were within the new attendance zone for Anderson, yet only 40 students attended school to register on the first day. White parents within the Anderson zone began selling their houses or finding places to rent elsewhere in the city to avoid sending their children to Anderson(30).

Just four days after school registration began, U.S. District Judge Jack Roberts declared his school integration plan for Austin a failure due to lack of enrollments, protests of white parents, and AISD concerns regarding white flight. The majority of the white students that had enrolled in Anderson withdrew and attended their previous schools(31). After the Supreme Court ruled in 1971 that busing was an acceptable solution to integrate schools, both AISD and HEW filed desegregation plans that allowed for busing of students, and AISD planned to close Anderson, Kealing Junior High, and St. John’s Elementary, just as they proposed in 1969, and this time Judge Roberts approved the plan. The new high school that Austin Public Schools built in 1953 was not even 20 years old. In addition, this desegregation plan meant that AISD and Judge Roberts placed the burden of integration firmly on the African American community, as the students at Anderson and Kealing were bused out of the community and into predominately white schools(32).

This final act of discrimination against Anderson and the Black students, parents, and leaders associated with the school also splintered Austin’s wider African American community. Wilhelmina Delco, the first African American on the AISD school board, noted that community “was completely lost because it was no longer a cohesive sense of community, not just because the kids were getting on the bus, but they were getting on different buses”(33). As the Black students and teachers scattered across the city attending their newly assigned schools, the community lost a key institution and what many considered the heart of the community. Many African American businesses closed in East Austin and their buildings sat vacant(34).

Integration and community devastation

However, Austin was not alone in choosing to close its Black schools to achieve integration. School districts across the South made the same choice. In Galveston, the school district downgraded its Black high school (Central) to a middle school. Other school districts closed Black high schools altogether and turned elementary schools into alternative school campuses. Closure of Black high schools meant the erasure of decades of community pride. Integrated schools did not retain the Black high school’s mascots, school colors, school songs, or school championships in athletics, music, and academics. In the case of Anderson, the school’s trophies and awards were removed and were going to be destroyed, but alumni and teachers came together to ensure the trophies found a new location, however, the pride associated with “the original” L.C. Anderson High School was no longer a part of Austin’s public school system(35).

L.C. Anderson’s name lives on in a high school opened in 1974 in northwest Austin, approximately 13 miles from the last location of the Black L.C. Anderson High School. The current L.C. Anderson has a different mascot – the Fighting Trojans, different school colors – blue and gold, and a racially diverse student body from the original school – the black and gold Yellow Jackets and an all-Black enrollment. Until 2019, the 1953 Anderson High School building still stood in East Austin, serving as AISD’s Alternative Learning Center and as the home of the East Austin Boys and Girls Club. It was one of Austin’s last remaining physical remnants of the segregated school system, and the alumni of the African American Anderson High School held reunions there every few years(36). Currently, AISD is redeveloping the site into a new high school. The only physical remnant of this historic place is the football field.

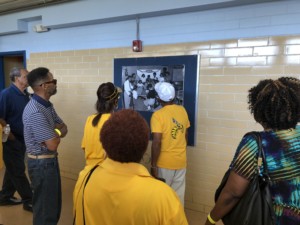

Original L.C. Anderson High School alumni view historic photographs of the school. (Credit: Rebekah Dobrasko, 2018)

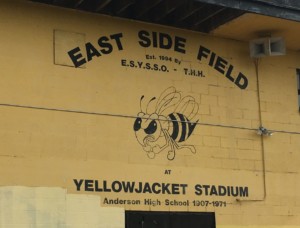

One of the only remaining original buildings associated with the African American L.C. Anderson High School. (Credit: Rebekah Dobrasko, 2018)

The impact of the original L.C. Anderson’s closure on the wider Black community in Austin was devastating. A former student observed, “it was like pulling a tree that was blossoming up from the roots and it dies, that’s what happened”(37). Integration, which was supposed to provide better education for African Americans, ultimately led to the loss of community institutions and community pride. While the original Anderson alumni association remains strong, the former students are aging, and, as one pointed out at the 2018 reunion, “they aren’t making no more Yellow Jackets.”

As the years pass, the histories of these Black community institutions fade into the past. The stories of schools like L.C. Anderson and other Black schools across the South are part of a larger story of the struggle for educational equality that continues to this day.

The school buildings and sites themselves are worthy of preservation and interpretation but are often erased from the landscape as school districts develop new schools or allow the historic Black high schools to deteriorate. The schools’ histories and their invested community pride and commitment, tell a uniquely American story of racism, segregation, pride, and achievement. Their stories deserve to be told.

REFERENCES

1. New Anderson High on most attractive sight (1953, August 25). The Austin Statesman, p. B13.

2. Koch and Fowler. (1928). A City Plan for Austin, Texas. Austin: City of Austin. (Reprinted by City of Austin in 1957).

3. Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971. Albany: State University of New York Press.

4. Franklin, Maria. (2012). I’m Proud to Know What I Know;” Oral Narratives of Travis and Hays Counties, Texas, c. 1920s-1960s (Vol. 1). Austin, TX: Texas Department of Transportation Archeological Studies Program, Report No. 136.

5. Lavergne, Gary M. (2010). Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall and the Long Road to Justice. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., page. 215

8. Austin Independent School District (1949, February 14). Meeting minutes. Austin: Author.

9. Adams, Matthew and Zachary Jones. (2017). Fighting for Anderson [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/5SADwvscryY

10. Austin Public Schools. (1948). Evaluation of the Anderson High School, Report of the Visiting Committee. Austin: Author.

11. Blackwell, Bruce, Producer. (2013-2016). Oral Histories of L.C. Anderson High School Alumni [Video files]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCM1hUsOVdr1YRuqq3ypdqTQ

Humanities Texas. (2000). Parallel and Crossover Lives: Texas Before and After Desegregation. Retrieved from https://www.humanitiestexas.org/programs/past/parallel-crossover

12. Austin Independent School District (1960). Ten Years of Growth, 1950-1960. Austin: Author

13. Austin Public Schools. (1950). Agenda for the Construction of the Proposed New High School for Colored. Austin: Division of School Plant.

14. Ibid.

15. Austin Education Association. (1960). Educational Institutions of Austin, Texas Historical Brochure. Austin: Author.

16. Dobrasko, Rebekah. (2005). Upholding ‘Separate but Equal:’ South Carolina’s School Equalization Program (Unpublished master thesis). University of South Carolina, Columbia.

17. Austin Education Association. (1960). Educational Institutions of Austin, Texas Historical Brochure. Austin: Author.

18. Kluger, Richard. (1976). Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

19. Kluger, Richard. (1976). Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971. Albany: State University of New York Press.

20. Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971, p.27. Albany: State University of New York Press.

21. Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Brewer, Anita. (1956, September 6). Schools Here Open Calmly. The Austin Statesman, p. A1.

22. Ibid.

23. Dobrasko, Rebekah. (2005). Upholding ‘Separate but Equal:’ South Carolina’s School Equalization Program (Unpublished master thesis). University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971. Albany: State University of New York Press.

24. Barry, Tom. (1968, August 2). Austin schools pressed on desegregation plan. The Austin Statesman, p. A2.

League of Women Voters. (1970). Austin: School Desegregation, A Fact Sheet. Austin: Author.

25. League of Women Voters. (1970). Austin: School Desegregation, A Fact Sheet. Austin: Author.

Humanities Texas. (2000). Parallel and Crossover Lives: Texas Before and After Desegregation. Retrieved from https://www.humanitiestexas.org/programs/past/parallel-crossover

Taylor, Lynn. (1969, May 29). Anderson High students petition to retain school. The Austin Statesman, p. A3.

26. Katz, Dale. (1969, September 9). Anderson integration “no strain.” The Austin Statesman, pp. A1, A6.

27. League of Women Voters. (1970). Austin: School Desegregation, A Fact Sheet. Austin: Author.

Wilson, Anna Victoria and William E. Segall. (2001). Oh, Do I Remember! Experiences of Teachers During the Desegregation of Austin’s Schools, 1964-1971. Albany: State University of New York Press.

28. League of Women Voters. (1970). Austin: School Desegregation, A Fact Sheet. Austin: Author.

29. Residents ponder plan’s effects. (1970, August 29). The Austin Statesman, p. 1, 8.

30. Anderson greets transfer group. (1970, September 1). The Austin Statesman, p. 1, 6.

31. Scott, Valerie. (1970, October 1). Redistrict Emotion. The Austin Statesman, p. B8

32. Marshall, Sarah. (Spring 2012). The Wake of Integration: Loss of a School and the Demise of a Community. Intersections: New Perspectives in Texas Public History, vol 1, no. 1, 38-47.

33. Humanities Texas. (2000). Parallel and Crossover Lives: Texas Before and After Desegregation. Retrieved from https://www.humanitiestexas.org/programs/past/parallel-crossover

34. McGee, Kate. (2016, October 12). Anderson High School Closed 45 Years Ago, But East Austin Still Feels its Absence. KUT News. Retrieved from https://www.kut.org/

35. Marshall, Sarah. (Spring 2012). The Wake of Integration: Loss of a School and the Demise of a Community. Intersections: New Perspectives in Texas Public History, vol 1, no. 1, 38-47.

Dobrasko, Rebekah. (2005). Upholding ‘Separate but Equal:’ South Carolina’s School Equalization Program (Unpublished master thesis). University of South Carolina, Columbia.

36. McGee, Kate. (2016, October 12). Anderson High School Closed 45 Years Ago, But East Austin Still Feels its Absence. KUT News. Retrieved from https://www.kut.org/

37. Marshall, Sarah. (Spring 2012). The Wake of Integration: Loss of a School and the Demise of a Community. Intersections: New Perspectives in Texas Public History, vol 1, no. 1, 38-47.