Since there were no major battles during the war in Texas, slave life in the state continued relatively unaffected, other than the influx of “refugee” slaves. Slave owners and male family members did venture off to fight for the Confederacy, leaving, in some cases, male slaves in charge of running plantations and farms. It’s possible that some of the refugees may have brought news to Texas slaves about emancipation, but with no real Union presence in the state, there were no opportunities for slaves to bolt to freedom.

The name “Old Three Hundred” is sometimes used to refer to the settlers who received land grants in Stephen F. Austin’s first colony. In January 1821 Austin’s father, Moses Austin, had received a permit from the Spanish to settle 300 families in Texas, but he died in Missouri a short time later before he could realize his plans. Stephen F. Austin took his father’s place and traveled to San Antonio, where he met with the Spanish governor Antonio María Martínez, who acknowledged him as his father’s successor. Austin quickly found willing colonists, and by the end of the summer of 1824 most of the Old Three Hundred were in Texas, forming the state’s first Anglo colony. An indication of the financial stature of the grantees was the large number of slaveholders among them; by the fall of 1825, sixty-nine of the families in Austin’s colony owned slaves, and the 443 slaves in the colony accounted for nearly a quarter of the total population of 1,790.

Needlepoint picture of a map of Austin’s Old 300 Colony.

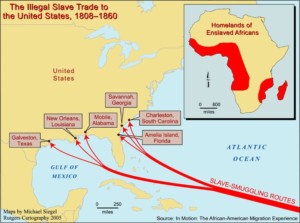

After 1808 it was illegal for Americans to participate in the international slave trade. This, however, did not mean that slaveholders were prohibited from trading slaves within the United States. Between 1808 and 1865, slaveholders in the upper South (Virginia, Maryland, etc.) sold hundreds of thousands of slaves to cotton planters in the Gulf Coast states. Writing at Smithsonian magazine, Edward Ball applies the phrase “trail of tears”–a phrase normally used to describe the Cherokee displacement in the 1830s–to this forced migration. “The Slave Trail of Tears is the great missing migration—a thousand-mile-long river of people, all of them black, reaching from Virginia to Louisiana. During the 50 years before the Civil War, about a million enslaved people moved from the Upper South—Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky—to the Deep South—Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama. They were made to go, deported, you could say, having been sold.”

At the turn of last century Eugene C. Barker, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin, conducted research on the illegal slave trade in Texas. Barker sought to unveil the obscure history of slave smuggling in Texas and he set out to collect information pertaining to that subject. Interested in the nineteenth century, particularly in the period from 1808 to the 1865 when the international slave trade was officially abolished and slavery ended in the United States, Barker wrote numerous letters to elderly residents of Texas asking for their recollections on anything related to the illegal slave trade in Texas during that period.

At the turn of last century Eugene C. Barker, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin, conducted research on the illegal slave trade in Texas. Barker sought to unveil the obscure history of slave smuggling in Texas and he set out to collect information pertaining to that subject. Interested in the nineteenth century, particularly in the period from 1808 to the 1865 when the international slave trade was officially abolished and slavery ended in the United States, Barker wrote numerous letters to elderly residents of Texas asking for their recollections on anything related to the illegal slave trade in Texas during that period.

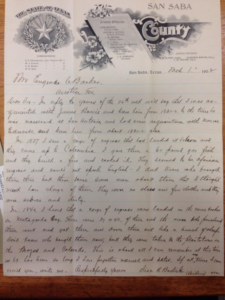

In March 1902, 80-year-old Sion R. Bostick, from San Saba County, replied to Barker with a letter containing a wealth of information. He remembered slave smuggling endeavors that occurred in the 1830s and added provocative and very specific information about two groups of African slaves who were illegally brought into the United States through Texas at that time. Bostick’s letter arrived as a one-page hand-written letter on fine-lined letterhead paper depicting the official star of Texas on the upper left-hand corner circled by an intricate drawing of olive wreaths adorned by flowers on the uppermost part of the page. (more)

Union attempts to occupy Texas were either limited to the state’s southern coastline, far away from the East Texas counties with the densest slave populations, or they were turned back before they even reached Texas. Only 30 percent of Texas families owned slaves in 1850, and only 2 percent of those held 20 or more slaves. However, Texans had not only fully grasped slaver-owning concepts, but were downright giddy about the future prospects of slaves cultivating the state’s fertile soil, especially its cotton crop. In the late 1850s, an editorial in Austin’s Texas State Gazette suggested that “until we reach somewhere in the vicinity of two millions of slaves, it is evident that such a thing as too many slaves in Texas is an absurdity.” Charles DeMorse of the Clarksville Northern Standard was more direct: “We want more slaves, we need them.”

Union attempts to occupy Texas were either limited to the state’s southern coastline, far away from the East Texas counties with the densest slave populations, or they were turned back before they even reached Texas. Only 30 percent of Texas families owned slaves in 1850, and only 2 percent of those held 20 or more slaves. However, Texans had not only fully grasped slaver-owning concepts, but were downright giddy about the future prospects of slaves cultivating the state’s fertile soil, especially its cotton crop. In the late 1850s, an editorial in Austin’s Texas State Gazette suggested that “until we reach somewhere in the vicinity of two millions of slaves, it is evident that such a thing as too many slaves in Texas is an absurdity.” Charles DeMorse of the Clarksville Northern Standard was more direct: “We want more slaves, we need them.”