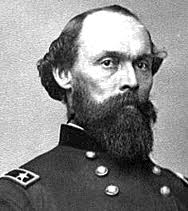

Union Gen. Gordon Granger and his 2,000 troops met no resistance when they arrived in Galveston, two and a half months after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender and three weeks after Gen. E. Kirby Smith had surrendered the last regular Texas Confederate soldiers at Galveston Island. Granger was sent to command the Department of Texas and among his major tasks was alerting Texas slaves about their freedom. The announcement set off joyful displays throughout the city.

(click images to enlarge)

Granger’s proclamation formed the basis for the annual “Juneteenth” festivities, which celebrate the end of slavery in Texas. Granger also declared that laws passed by the Confederate government were void, that Confederate soldiers were paroled, that all persons having public property, including cotton, should turn it in to the United States Army, and that all privately owned cotton was to be turned in to the army for compensation. (more)

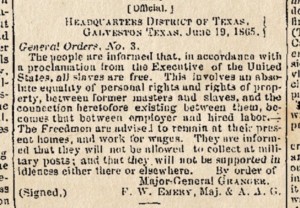

General Order No. 3

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Genealogist and educator Sharon Batiste Gillins, a Galveston native, said this about the day of the announcement:

“In the days and weeks that led up to the 19th of June, the newspapers were filled with the latest stories, reports and editorials about the end of the War, the beginning of the peace and the imminent freedom of the enslaved Africans. On June 14th. Galveston Daily News reported that Federal troops would soon arrive in Galveston. The announcement quickly spread throughout the white and black community and the city’s residents were overcome with a curious mix of anticipation and anxiety. Uncertainty permeated the air as they contemplated the consequences of the War’s end and the arrival of Federal troops into the city. Each segment of the population experienced a different set of emotions, the unknown and imagined consequences dissected in print from every angle. That is, every angle except that of the enslaved people whose destiny and very lives would be most impacted.”

The fear and uncertainty about emancipated slaves was evidenced in stories appearing in the Galveston newspaper, wondering about the white citizens’ plight, economically and socially, under “a government in which we have now no voice.” Another piece, in the Galveston Tri-Weekly News, on June 21: “This attempt to overthrow an institution that has become a part of our social system and which our entire population has believed essential to the welfare of both races, led to the war … and all we can do in our present entire dependence on the clemency of our conquerors, is to repeat to them what we have been urging for so many years … that the attempt to set the negro free from all restraint and make him politically the equal of the white man, will be most disastrous to the whole country and absolutely ruinous to the South.”

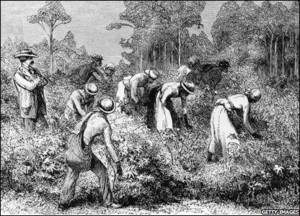

Why had it taken so long for the word about emancipation to reach this state? There are varying accounts, some myths, of why the news was delayed in getting to Texas, but most likely slave owners were aware of the proclamation but ignored it and kept their slaves busy harvesting crops. Also, the lack of Union troops in Texas during the war prohibited enforcement.

Slaves pick cotton under the watchful eye of their master. For those slave-holding families that did not own many slaves, it was not uncommon for owners and their families to work alongside their slaves in the field. (more)

Osterman Building – Left Foreground, Picturesque Galveston, 1900. Granger may have announced Gen. Order No. 3 from this building, Galveston Historical Foundation

Galveston dock workers, year unknown. Dockworkers in 1863 were among the first to hear the announcement about freedom.