The 1968 Kerner Commission Got It Right, But Nobody Listened

Released 50 years ago, the infamous report found that poverty and institutional racism were driving inner-city violence

(Smithsonianmag.com) Pent-up frustrations boiled over in many poor African-American neighborhoods during the mid- to late-1960s, setting off riots that rampaged out of control from block to block. Burning, battering and ransacking property, raging crowds created chaos in which some neighborhood residents and law enforcement operatives endured shockingly random injuries or deaths. Many Americans blamed the riots on outside agitators or young black men, who represented the largest and most visible group of rioters. But, in March 1968, the Kerner Commission turned those assumptions upside-down, declaring white racism—not black anger—turned the key that unlocked urban American turmoil.

Bad policing practices, a flawed justice system, unscrupulous consumer credit practices, poor or inadequate housing, high unemployment, voter suppression, and other culturally embedded forms of racial discrimination all converged to propel violent upheaval on the streets of African-American neighborhoods in American cities, north and south, east and west. And as black unrest arose, inadequately trained police officers and National Guard troops entered affected neighborhoods, often worsening the violence. (more)

The ‘Silent’ Protest That Kick-Started the Civil Rights Movement

Nearly 50 years before the March on Washington, African Americans took to the streets of New York to protest racial inequality.

(History.com) At 1 p.m. on Saturday, July 28, 1917, a group of between 8,000 and 10,000 African American men, women and children began marching through the streets of midtown Manhattan in what became one of the first civil rights protests in American history—nearly 50 years before the March on Washington. Accompanied only by the sound of drums as they moved down Fifth Avenue, the protestors marched in silence, mourning those killed in a wave of anti-African American violence that had swept across the nation.

In the year preceding the march, two notorious lynching attacks had made headlines; one in Waco, Texas, which saw 10,000 people gather to watch a black man hung, and another in Tennessee that drew a crowd of 5,000. Even more shocking were the race riots that broke out in East St. Louis, Illinois, in the spring and summer of 1917.

Racial tensions in the city had been rising for years, as waves of southern blacks fled the Jim Crow South, traveling to industrial cities in the north in search of better living conditions and employment opportunities as part of what is known as the Great Migration. (more)

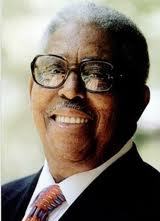

Thomas Freeman, celebrated TSU debate coach, dies at 100

Dr. Thomas Freeman, founding dean of the Texas Southern University Honors College and longtime debate team director. (Photo: Brett Coomer, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer)

(Houston Chronicle) Thomas Freeman, the renowned professor and debate coach whose relationship with Texas Southern University spanned eight decades, died Saturday (June 6, 2020), his son confirmed. He was just days from turning 101.

Carlotta Freeman said her father died of natural causes.

Born in Richmond, Va., Freeman was determined, faithful and passionate about preaching, delivering his first sermon at age 9. He graduated high school at 15 and earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Virginia Union University, a bachelor’s degree in divinity from Andover Newton Seminary in Massachusetts and a doctorate in homiletics — the art of preaching — from the University of Chicago in 1948.

Freeman joined the TSU faculty in 1949 to teach philosophy. As a trained preacher, he planned to return to the pulpit at Carmel Baptist Church in Richmond, Va., at the end of the school year. After Freeman assigned students a debate in a logic course, the president of the historically black university persuaded him to stay permanently as the debate coach.

Over his 70-year tenure, Freeman became a legend on the Third Ward campus, training students and celebrities alike in forensic speech, or the study of public speaking and debate. He worked with U.S. Reps. Mickey Leland and Barbara Jordan, Harris County Commissioner Rodney Ellis, gospel superstar Yolanda Adams and actor Denzel Washington, who sought out Freeman’s expertise to coach the cast of the Golden Globe-nominated film “The Great Debaters.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Racial Borders, Black Soldiers along the Rio Grande,” by James N. Leiker.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Racial Borders, Black Soldiers along the Rio Grande,” by James N. Leiker.

- 2002 T.R. Fehrenbach Award, presented by the Texas Historical Commission

- 2003 Southwest Book Award, presented by the Border Regional Library Association

When the Civil War ended, hundreds of African Americans enlisted in the U.S. Army to gain social mobility and regular paychecks. Stationed in the West prior to 1898, these black soldiers protected white communities, forced Native Americans onto government reservations, patrolled the Mexican border, and broke up labor disputes in mining areas. African American men, themselves no strangers to persecution, aided the subjugation of Indian and Hispanic peoples throughout the West. It can hardly be surprising, then, that the relations among these groups became complex and often hostile–hardly surprising, but rarely examined.

Despised by the white settlers they protected, many black soldiers were sent to posts along the Texas-Mexico border— perceived to be a “safe place to put them.” The interactions there among blacks, whites, and Hispanics during the period leading up to the Punitive Expedition and World War I offer the opportunity to study the complicated, even paradoxical nature of American race relations. James N. Leiker has applied the sophisticated perspectives of new social history to the experience of the buffalo soldiers and their legacy in southern and western Texas in an effort to gain new insight about race in the West.

Racial Borders establishes the army’s fundamental role in transforming the Rio Grande from a “frontier” into a “border” and shows how that transformation itself brought a tightening of racial and national categories. But more importantly, it warns about the dangers of simplifying history into groupings of “white and non-white,” “oppressors and oppressed.”

Leiker draws on Mexican and U.S. military records and Texas state and black national newspapers to do more than provide an account of the shifting loyalties of race and nationalism along the Rio Grande over a fifty-year span; he reminds scholars and reformers about the tangled history of race relations in America.

This Week in Texas Black History

June 7

On this day in 1950, John Chase enrolled in the University of Texas School of Architecture graduate program, becoming the first African-American to enroll at a major university in the South. Chase, a native of Annapolis, Md., earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first black graduate of the University. That same year, he also became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade. In 1980, he became the first African-American appointed to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts. His firm’s designs include: the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, the Harris County Astrodome Renovation, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University.

June 9

On this date in 1965 the University Interscholastic League State Executive Committee validated the Legislative Council’s decision to open league membership to all public schools. The UIL was formed in 1913 with the stipulation that its membership was open only to white schools. In 1920, the Prairie View Interscholastic League was formed as the UIL’s counterpart to govern academic and athletic competitions for the state’s high schools for black students. Black schools began UIL competition in the 1967-68 school year. After the 1969-70 school year, the UIL fully absorbed all PVIL member schools. The PVIL played a leading role in developing African-American students in the arts, literature, athletics and music from the 1920’s through 1970. Among its football stars, alone, were: Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Ernie Ladd (Orange Wallace), and Jerry Levias (Beaumont Hebert).

June 11

On this day in 1991, Connie Yerwood died in Austin. In 1937, she became the first African American doctor to work for Texas Public Health Services. The Victoria native would also become the first black director of Maternal and Child Services in Texas and the first black chief of the Bureau of Personal Health Services. Connor attended public school in Austin and graduated from the Samuel Huston College Academy in 1925. She received the bachelor of arts degree cum laude from Samuel Huston College (now Huston-Tillotson College). In 1933 she graduated cum laude from Meharry Medical School. She began her residency in pediatrics but became interested in public health. She earned a scholarship to study public health at the University of Michigan and returned to Texas in 1937, when she joined the Texas Public Health Service. During the early years of her work with the state health agency, Connor was responsible for training midwives in East Texas. She also served as a consultant in setting up health clinics that offered services such as well-baby clinics and prenatal care to the rural poor of Texas. In the beginning, her duties were limited to work among the black population in East Texas, but as the need and demand grew she eventually worked with all cultures throughout the state. She led the state’s efforts in early periodic screening diagnosis, treatment, and chronic diseases for pregnancy and pediatrics. When she retired on August 31, 1977, she was director of health services. Yerwood was a long-time trustee of Samuel Huston College and the president of its National Alumni Association.

June 11

James Leonard Farmer, Sr., who normally wrote his name “J. Leonard Farmer” on all of his publications, was born on this date in Kingstree, South Carolina in 1886. Farmer became Texas’ first black professor with an earned Ph.D (Boston University 1918), pastored churches in Texarkana, Marshall and Galveston and taught at Wiley College in Marshall (1919-20 and 1934-39) and Samuel Huston (later Huston-Tillotson) (1925-30 and 1946-56), in Austin. His son, James Farmer, Jr., was a noted Civil Rights activist and founder of CORE and was one of Wiley’s “Great Debaters.”

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

It’s OK now

Hopefully, this COVID-19 pandemic will end soon, and life can get back to normal. At the very least, as a society, I hope we’ll learn how to live with it. But one day, our intelligentsias will analyze every governmental action since February and March of 2020, especially those of the President. Recent policies have addressed the numbers of individuals who are out of work because of the “stay at home” directives. It’s been called… (more)

WWJD

Several years ago, these letters, “WWJD?” seemed to be everywhere. We all know they represent “What Would Jesus Do?” I think these letters and the question were meant to challenge society to consider the moral implications of their everyday decisions. Now in this new COVID-19 reality, WWJD may have new meaning. Since my father…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.