Jacob Lawrence’s ‘Struggle’ Series Prepares to Be Seen by a New Generation

For the first time in decades, view a major reimagining of the battles that made the nation

(Image: Victory and Defeat, Panel 13 from “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” 1954-56, by Jacob Lawrence. (Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Bob Packert / PEM)

(Smithsonian Magazine) A modernist master and black history’s pre-eminent visual storyteller, Jacob Lawrence completed his most famous set of paintings in 1941, when he was just 23. A sweeping view of African-Americans’ mass exodus from the Jim Crow South—laid out over 60 color-saturated tempera panels—his “Migration Series” is still considered one of the major achievements in 20th-century American art.

But another series by Lawrence, equally ambitious in scope and radical in vision, had been largely forgotten until this year, when the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts, organized a new traveling exhibition, scheduled next for New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is the first showing in more than 60 years of Lawrence’s “Struggle: From the History of the American People.”

These 30 hardboard panels, each 12 by 16 inches, cover the period from the American Revolution until 1817. (more)

More art: “Rediscovering Black Portraiture through the Getty Museum Challenge” — As COVID-19 closed in on the United Kingdom in mid-March, opera singer and BBC broadcaster Peter Brathwaite was abruptly left with time he didn’t want: all of his upcoming performances were canceled until August. He kept busy practicing and researching for future shows, but was still “twiddling his thumbs a bit.” But then he came across the Getty Museum Challenge—an invitation to recreate a famous work of art using props from around your home; a fellow opera singer had posted a photo on Twitter of herself as Johannes Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. Braithwaite thought, what can I recreate? (more)

Dallas Area Freedom Colonies

In the late 1800s, recently emancipated African Americans settled across Texas, forming communities called Freedmen’s Towns, or Freedom Colonies.

In the late 1800s, recently emancipated African Americans settled across Texas, forming communities called Freedmen’s Towns, or Freedom Colonies.

Dallas Freedom Colonies, when examined together, reveal patterns of systematic demolition, relocation, and lack of services. Many of these communities and much of their histories have been destroyed as a result.

This storymap was created as part of a Fall 2018 graduate-level Critical Place Studies course taught by Dr. Andrea Roberts at Texas A&M University. It aims to contribute to the Texas Freedom Colonies Project by documenting three historic African American settlements in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

If you have a story or information about these or other communities, please share them with the project! You can do this by visiting the Texas Freedom Colonies Project website. (more)

A Survivor of the Last Slave Ship Lived Until 1940

Matilda McCrear came to the United States on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to arrive on U.S. shores.

(History.com) The last known survivor of the last U.S. slave ship died in 1940—75 years after the abolition of slavery. Her name was Matilda McCrear.

When she first arrived in Alabama in 1860, she was only two years old. By the time she died, Matilda had lived through the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws, World War I, the Great Depression and the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

The facial scars on her left cheek—which are preserved in photographs—indicate she came from the Yoruba people of West Africa. Her given name was “Àbáké,” meaning “born to be loved by all.” She and her mother and sisters were captured from their home by the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey and taken to the slave port of Ouidah in present-day Benin. There, Captain William Foster and his crew illegally purchased her family and over 100 others to traffic into Alabama on the Clotilda, the last known U.S. slave ship (the importation of enslaved people had been illegal in the U.S. since 1807). (more)

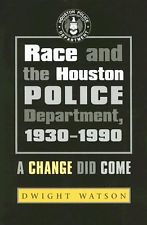

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Race and the Houston Police Department, 1930–1990, A Change Did Come,” by Dwight D. Watson.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Race and the Houston Police Department, 1930–1990, A Change Did Come,” by Dwight D. Watson.

In Houston, as in the rest of the American South up until the 1950s, the police force reflected and enforced the segregation of the larger society. When the nation began to change in the 1950s and 1960s, this guardian of the status quo had to change, too. It was not designed to do so easily.

Dwight Watson traces how the Houston Police Department reacted to social, political, and institutional change over a fifty-year period—and specifically, how it responded to and in turn influenced racial change.

Using police records as well as contemporary accounts, Watson astutely analyzes the escalating strains between the police and segments of the city’s black population in the 1967 police riot at Texas Southern University and the 1971 violence that became known as the Dowling Street Shoot-Out. The police reacted to these events and to daily challenges by hardening its resolve to impose its will on the minority community.

By 1977, the events surrounding the beating and drowning of Jose Campos Torres while in police custody prompted one writer to label the HPD the “meanest police in America.” This event encouraged Houston’s growing Mexican American community to unite with blacks in seeking to curb police autonomy and brutality.

Watson’s study demonstrates vividly how race complicated the internal impulses for change and gave way through time to external pressures—including the Civil Rights Movement, modernization, annexations, and court-ordered redistricting—for institutional changes within the department. His work illuminates not only the role of a southern police department in racial change but also the internal dynamics of change in an organization designed to protect the status quo.

This Week in Texas Black History

Jun 4

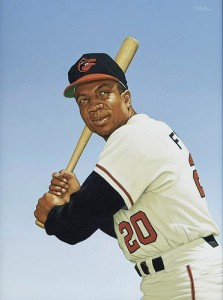

Frank Robinson

In 1991, on this day, Baltimore Orioles manager Frank Robinson was named assistant general manager of the club, only the third African American to become an assistant GM. As a player with the Orioles, Robinson, a Beaumont, Texas native, won the triple crown (leading the league in home runs (49), runs batted in (122), and batting average (.316) in 1966. Robinson began managing the Cleveland Indians in 1975 as the first African American to manage a major league team. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

Jun 5

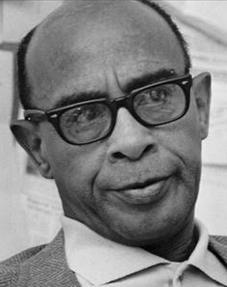

Heman Sweatt

On this day in 1950, The U.S. Supreme Court ordered Heman Sweatt admitted to the University of Texas Law School. In handing down its decision in Sweatt v. Painter, the Court concluded that black law students were not offered substantial quality in educational opportunities and that Sweatt could therefore not receive an equal education in a separate law school. Sweatt, a Houstonian, had teamed with the NAACP to challenge the admissions policy at the UT Law School. The NAACP was looking to test separate but equal education statutes in Texas and the result of Sweatt’s legal battle struck down segregationist policies at the school (for graduate and professional programs only), gained him admission, and paved the way for the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which opened integration for undergraduates.

Jun 6

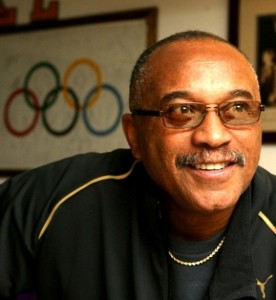

Tommie Smith

On this day in 1944, Olympic sprint champion Tommie Smith was born in Clarksville, Texas. The seventh of 12 children, he survived a life-threatening bout of pneumonia as an infant. Smith is the only man in the history of track and field to hold 11 world records simultaneously. At San Jose State University, he tied or broke 13 world records. However, he is most remembered as one half of the duo of black U.S. Olympians – along with John Carlos – who, during the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, stood on the victory stand with heads bowed and raised clinched fists in a demonstration for human rights, liberation and solidarity. The protest overshadowed Smith’s performance on the track where he broke the world and Olympic records, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter sprint with a time of 19.83 seconds. The story of the “silent gesture” is captured in the 1999 HBO-TV documentary, “Fists of Freedom.” In 1978, Smith was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and has accumulated many other honors.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

It’s OK now

Hopefully, this COVID-19 pandemic will end soon, and life can get back to normal. At the very least, as a society, I hope we’ll learn how to live with it. But one day, our intelligentsias will analyze every governmental action since February and March of 2020, especially those of the President. Recent policies have addressed the numbers of individuals who are out of work because of the “stay at home” directives. It’s been called… (more)

WWJD

Several years ago, these letters, “WWJD?” seemed to be everywhere. We all know they represent “What Would Jesus Do?” I think these letters and the question were meant to challenge society to consider the moral implications of their everyday decisions. Now in this new COVID-19 reality, WWJD may have new meaning. Since my father…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.