The Damning History Behind UT’s ‘The Eyes of Texas’ Song

Student athletes wrote a letter urging officials to change the tune, which has racist origins.

(Texas Monthly) On June 4, after one of their first in-person practices since the coronavirus outbreak, the Texas Longhorns football team lined up outside Darrell K Royal—Texas Memorial Stadium and began to march toward downtown Austin. They were joining thousands of others across the world protesting the killing of George Floyd; when they reached the Texas Capitol, players, coaches, and support staff knelt in silence for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time Floyd was pinned to the ground with a policeman’s knee on his neck. Then head coach Tom Herman addressed his players: “You’re a minority football player at one of the biggest brands in the country. You have a voice. Use it.”

His players took that message to heart. Days later, a group of more than two dozen Texas student athletes—including football, basketball, and track stars—posted a letter on social media in which they vowed not to participate in upcoming recruiting or fund-raising events until the university administration addressed a series of concerns. Those included renaming certain buildings on campus that are named for men who supported the Confederacy or segregation, creating an outreach program for underprivileged communities, and establishing a permanent exhibit centered on the history of black athletes in the Texas Athletics Hall of Fame, which opened last year and features statues of running backs Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams. “As ambassadors, it is our duty to utilize our voice and role as leaders in the community to push for change to the benefit of the entire UT community,” they wrote. In particular, the final item on the players’ agenda has ignited a debate throughout the Longhorn community over the past week: they called for officials to replace “‘The Eyes of Texas’ with a new song without racial undertones.” (more)

Meet Lena Richard, the Celebrity Chef Who Broke Barriers in the Jim Crow South

Lena Richard was a successful New Orleans-based chef, educator, writer and entrepreneur

Cookbook author Lena Richard (above with her daughter and sous chef Marie Rhodes) was the star of a 1949 popular 30-minute cooking show, airing on New Orleans’ WDSU-TV. (Courtesy of Newcomb Archive, Vorhoff Library Special Collections, Tulane University)

(Smithsonian Magazine) In 1949, nearly a year after New Orleans’ WDSU-TV went live for the first time, Lena Richard, an African American Creole chef and entrepreneur, brought her freshly prepared dishes to a family-style kitchen TV set and took to the screen to film her self-titled cooking show—the first of its kind for an African American.

“Her reputation was very fine,” says Marie Rhodes, Richard’s daughter and sous chef. “Everybody used to call her Mama Lena.”

The show, titled “Lena Richard’s New Orleans Cook Book” was one of the earliest offerings on the station, and became so popular that WDSU-TV began airing her show twice weekly on Tuesdays and Thursdays. While the program welcomed a racially mixed audience, the majority were white middle- and upper-class women, who leaned on Richard’s culinary expertise for all things Creole.

“Richard’s ability to share her recipes on TV—in her own words, and as the star of her own program—was an important and fairly exceptional departure within the media culture at the time,” says Ashley Rose Young, a historian and curator at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who has done extensive research into the life and legacy of the New Orleans chef. (more)

TIPHC online exhibit: “Juneteenth: The Apocalyptic Regeneration”

With those words, the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass described emancipation and the new national course for race relations and a new path of independence for newly-freed African Americans who had been held in bondage since 1619 when the first African slaves arrived in Jamestown, Va. to firmly establish “the peculiar institution” in the burgeoning American colonies. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation would free slaves in the rebellious states on January 1, 1863 but that news would not be officially delivered to Texas until June 19, 1865, a day that has become known as “Juneteenth.”

With those words, the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass described emancipation and the new national course for race relations and a new path of independence for newly-freed African Americans who had been held in bondage since 1619 when the first African slaves arrived in Jamestown, Va. to firmly establish “the peculiar institution” in the burgeoning American colonies. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation would free slaves in the rebellious states on January 1, 1863 but that news would not be officially delivered to Texas until June 19, 1865, a day that has become known as “Juneteenth.”

In commemoration of Juneteenth, the TIPHC is presenting an online exhibit, “The Apocalyptic Regeneration,” examining through images how freedom finally came to Texas, what was the reaction that day in Galveston, where the news was first announced by Union Gen. Gordon Granger, how the word was spread throughout the state to 250,000 enslaved Black Texans, and what the edict meant for African Americans who set out, for the first time, unshackled – emotionally and physically – and free to decide their own fates. They built towns (“Freedom Colonies”), schools, churches, businesses, and families they could raise and nurture without the threat of forced separation.

“Everybody went wild. We all felt like heroes … just like that we were free,” remembered Felix Haywood, a former slave in San Antonio who spoke in the Slave Narratives. “It didn’t seem to make the whites mad, either. They went right on giving us food just the same. Nobody took our homes, but right off colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get close to freedom … like it was a place or a city.”

The exhibit will be posted Thursday afternoon (June 18, 2020) and accessible through the TIPHC homepage (pvamu.edu/tiphc).

TIPHC Bookshelf

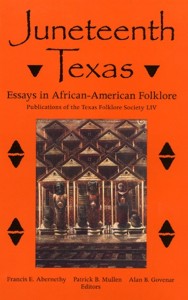

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas, Essays in African-American Folklore,” edited by Francis Edward Abernethy, Patrick B. Mullen and Alan B. Govenar.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas, Essays in African-American Folklore,” edited by Francis Edward Abernethy, Patrick B. Mullen and Alan B. Govenar.

Juneteenth Texas explores African-American folkways and traditions from both African-American and white perspectives. Included are descriptions and classifications of different aspects of African-American folk culture in Texas; explorations of songs and stories and specific performers such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Manse Lipscomb, and Bongo Joe; and a section giving resources for the further study of African Americans in Texas.

This Week in Texas Black History

Jun 14

In 1854, on this date, famous cowboy Nat Love, “Deadwood Dick,” was born as a slave on Robert Love’s plantation in Davidson County Tennessee. (Nat is pronounced “Nate.”) Love became proficient at breaking horses, and at age 15, headed west with $50 in his pocket to seek work as a cowboy. In Dodge City, Kansas, he met the crew of the Duval Ranch at the conclusion of their cattle drive and returned with them to Texas to work at the ranch. The teenager quickly adapted to cowboy life and excelled as a ranch hand and a marksman with his .45 revolver. He earned the name, “Deadwood Dick,” after winning an all-around cowboy contest in Deadwood, S.D. The contestants competed in roping, bridling, saddling, and shooting and Love finished first in each category, walking away with the $200 prize and a new nickname.

Jun 15-16

On these days in 1943, the Beaumont Riots occurred. Conditions in the city were already tense because blacks and whites were competing for jobs in the shipyards because of World War II and because of a lack of enough resources, traditionally segregated facilities were forced to integrate. The situation escalated when a white woman reported being raped by a black man, though she was unable to identify the suspect being held at the city jail. However, on the evening of June 15 more than 2,000 workers, plus perhaps another 1,000 interested bystanders, marched toward City Hall, then dispersed into small bands and began breaking into stores in the black section of downtown Beaumont. With guns, axes, and hammers, they proceeded to terrorize black neighborhoods in central and north Beaumont. Many blacks were assaulted, several restaurants and stores were pillaged, a number of buildings were burned, and more than 100 homes were ransacked. More than 200 people were arrested, fifty were injured, and two – one black and one white – were killed. Another black man died several months later of injuries received during the riot. Beaumont was among several U.S. cities that experienced violent race riots that summer, including Detroit, Harlem, and Mobile, Ala.

Jun 15

On this date in 1921, Bessie Coleman, from Atlanta, Texas, became the first licensed black pilot in the world when she earned an international aviation license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. As a barnstorming stunt pilot, she became known as “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie.” In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bessie’s honor and in 2000 she was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. The main road to Atlanta’s airport is named Bessie Coleman Drive.

Jun 18

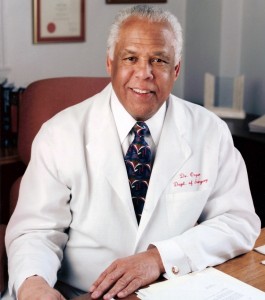

On this day in 2005, renowned surgeon and educator Claude H. Organ, Jr. died in Berkeley, Ca. of heart-related problems at age 78. A Marshall native, Organ was accepted to the University of Texas medical school, but when the school discovered he was black, it offered to pay the difference in tuition for him to attend another school. He graduated from Xavier University a black college in New Orleans and later received a degree from Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha. Organ developed two successful surgical residency programs, first at Creighton and later at the University of California/Davis-University of California, San Francisco East Bay Surgery Department. During his tenure at San Francisco he served as the first African American editor of the Archives of Surgery, the largest surgical journal in the English-speaking world.

Jun 19

On this day in 1865, Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and delivered the news about the Emancipation Proclamation, which had originally been issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Granger, possibly from a balcony at Ashton Villa, one of the state’s first brick structures, read General Order No. 3, which officially freed 250,000 slaves in Texas. The order read: “The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” In 1979, Governor William P. Clements signed an act introduced by freshman Democratic state representative Al Edwards (Houston) making Texas the first to officially make June 19, “Juneteenth”, a state holiday.

Jun 20

On this day in 1967, a jury in federal court in Houston found heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali guilty of draft evasion. Ali, who had a residence in Houston at the time, was known to the government as Cassius Clay and was sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Ali’s contention was that the draft boards in Louisville, Ky., his hometown, and in Houston had acted improperly by not granting him a deferment as a minister in the Nation of Islam, however, he was convicted of violating the U.S. Selective Service laws by refusing to be drafted. He had been ordered to report to a Houston induction station on April 28, 1967 and did, but refused to step forward when his named was called, afterwards saying, ”Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” He was immediately stripped of his boxing license and his title and was banned from boxing for three years. He stayed out of prison as his case was appealed. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and on June 28, 1971 (Clay, aka Ali, v. United States) the Court ruled 8-0, with Justice Thurgood Marshall abstaining, that Ali met the three standards for conscientious objector status: that he opposed war in any form, that his beliefs were based on religious teaching and that his objection was sincere. However, Ali had already resumed boxing on October 26, 1970, knocking out Jerry Quarry in Atlanta in the third round.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

It’s OK now

Hopefully, this COVID-19 pandemic will end soon, and life can get back to normal. At the very least, as a society, I hope we’ll learn how to live with it. But one day, our intelligentsias will analyze every governmental action since February and March of 2020, especially those of the President. Recent policies have addressed the numbers of individuals who are out of work because of the “stay at home” directives. It’s been called… (more)

WWJD

Several years ago, these letters, “WWJD?” seemed to be everywhere. We all know they represent “What Would Jesus Do?” I think these letters and the question were meant to challenge society to consider the moral implications of their everyday decisions. Now in this new COVID-19 reality, WWJD may have new meaning. Since my father…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.