The Thorny History of Reparations in the United States

In the 20th century, the country issued reparations for Japanese American internment, Native land seizures, massacres and police brutality. Will slavery be next?

Photo: President Harry S. Truman signing a bill providing for the establishment of the Indian Claims Commission. (Thomas D. Mcavoy/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

(History) The papers were handed out one by one to the elderly recipients—most frail, some in wheelchairs. To some, it may have looked like a run-of-the-mill governmental ceremony with the usual federal fanfare. But to Norman Mineta, a California congressman and future Secretary of Transportation, the 1990 event was deeply symbolic.

The papers were checks for $20,000, accompanied by a letter of apology for the internment of over 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. They were the first issued under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, a historic law that offered monetary redress to over 80,000 people.

Mineta had spearheaded the law, fighting for a government apology and financial redress for nearly a decade. As he watched, he flashed back to his own internment during the war, first at a racetrack, then at Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in Wyoming. His family had been forced to leave their home and business behind.

Now, Mineta felt, the government had finally begun the process of reconciliation. “The country made a mistake, and admitted it was wrong,” he says. “It offered an apology and a redress payment. To me, the beauty and strength of this country is that it is able to admit wrong and issue redress.”

Today, the law is remembered as the most successful push for reparations for a historic wrong in U.S. history. But the United States’ track record of reparations and official apologies is scattershot—and it has yet to tackle one of its most glaring injustices—the enslavement of African Americans. Many argue that slavery in America has legacies that continue to shape society today. (more)

William Tucker: First African born in Colonial America

(blackpast.org) William Tucker was the first person of African ancestry born in the 13 British Colonies. His birth symbolized the beginnings of a distinct African American identity along the eastern coast of what would eventually become the United States.

(blackpast.org) William Tucker was the first person of African ancestry born in the 13 British Colonies. His birth symbolized the beginnings of a distinct African American identity along the eastern coast of what would eventually become the United States.

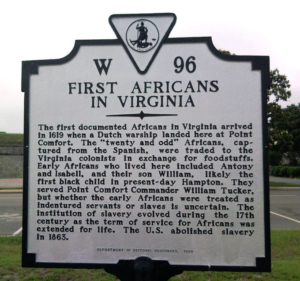

William Tucker was born in 1624 near Jamestown, Virginia, the son of “Antoney and Isabell,” two African indentured servants. Historians do not know much of William Tucker’s life due to the fragmented pieces of primary source material available for contemporary study.

According to the 1624-1625 Virginia Census, 22 Africans lived in Virginia at the time of Tucker’s birth. The first 20 of these Africans arrived in 1619 and all of them worked under indentured servitude contracts. These men and women were not slaves because Virginia’s General Assembly had not yet worked out the terms for enslavement in the colony. Consequently these first Africans in Virginia received the same rights, duties, privileges, responsibilities, and punishments as their white indentured counterparts from Great Britain. They also worked under the same terms and many but not all were given land at the end of their period of indenture. In fact they and their descendants became the nucleus of the free black population which existed in Virginia prior to the Civil War. (more)

Documenting Slave Voyages

Led by Emory, a massive digital memorial shines new light on one of the most harrowing chapters of human history

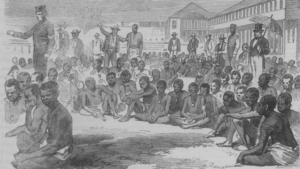

Published in The Illustrated London News on June 20, 1857, this image depicts the capture of the slave ship “Zeldina” and the conditions of the enslaved people who were onboard. (Reproduced courtesy Emory’s Rose Library.)

(Emory University) For African American families seeking clues to their ancestry, the task is too often stymied by a history that defies documentation.

In fact, the drive toward discovery frequently ends abruptly with the scant record-keeping that surrounds the American slave trade — people kept as property with names simply lost to history.

So when Henry Louis Gates Jr. works with guests on the acclaimed PBS program “Finding Your Roots” whose family stories have been obscured by slavery, he routinely looks for clues in Emory University’s “Slave Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database.”

“And it’s a gold mine,” says Gates, director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University — an early supporter of the Slave Voyages project — who calls it “one of the most dramatically significant research projects in the history of African studies, African American studies and the history of world slavery itself.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Advancing Democracy — African Americans and the Struggle for Access and Equity in Higher Education in Texas,” by Amilcar Shabazz.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Advancing Democracy — African Americans and the Struggle for Access and Equity in Higher Education in Texas,” by Amilcar Shabazz.

2004 T. R. Fehrenbach Book Award, Texas Historical Commission

As we approached the fiftieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), it was important to consider the historical struggles that led to this groundbreaking decision. Four years earlier in Texas, the Sweatt v. Painter decision allowed blacks access to the University of Texas’s law school for the first time. Amilcar Shabazz shows that the development of black higher education in Texas–which has historically had one of the largest state college and university systems in the South–played a pivotal role in the challenge to Jim Crow education.

Shabazz begins with the creation of the Texas University Movement in the 1880s to lobby for equal access to the full range of graduate and professional education through a first-class university for African Americans. He traces the philosophical, legal, and grassroots components of the later campaign to open all Texas colleges and universities to black students, showing the complex range of strategies and the diversity of ideology and methodology on the part of black activists and intellectuals working to promote educational equality. Shabazz credits the efforts of blacks who fought for change by demanding better resources for segregated black colleges in the years before Brown, showing how crucial groundwork for nationwide desegregation was laid in the state of Texas.

Sept. 1

On this day in 1990, Dr. Marguerite Ross Barnett became president of the Univ. of Houston and the first black woman to lead a major American university. From Charlottesville, Virginia she grew up in Buffalo, New York and earned a political science degree from Antioch College and master’s and doctorate degrees in political science from the University of Chicago. A recognized scholar in political science, she taught at Princeton, Howard, and Columbia universities. At UH, she succeeded in raising more than $150 million for the institution, establishing the Texas Center for Environmental Studies, and instituting the nationally renowned Bridge Program, which aided and motivated disadvantaged students to make a successful transition from high school to college. Barnett died of complications from a neuro-endocrinological condition on February 26, 1992.

On this day in 1990, Dr. Marguerite Ross Barnett became president of the Univ. of Houston and the first black woman to lead a major American university. From Charlottesville, Virginia she grew up in Buffalo, New York and earned a political science degree from Antioch College and master’s and doctorate degrees in political science from the University of Chicago. A recognized scholar in political science, she taught at Princeton, Howard, and Columbia universities. At UH, she succeeded in raising more than $150 million for the institution, establishing the Texas Center for Environmental Studies, and instituting the nationally renowned Bridge Program, which aided and motivated disadvantaged students to make a successful transition from high school to college. Barnett died of complications from a neuro-endocrinological condition on February 26, 1992.

Sept. 2

E.H. Anderson was born on this day in 1850 in Memphis, Tenn. Anderson would become the second principal for Prairie View State Normal School (Prairie View A&M University) in 1879. At the time, the school’s enrollment was only 50 students.

E.H. Anderson was born on this day in 1850 in Memphis, Tenn. Anderson would become the second principal for Prairie View State Normal School (Prairie View A&M University) in 1879. At the time, the school’s enrollment was only 50 students.

Sept. 2

On this date in 1946, musician William Everett “Billy” Preston was born in Houston. A child prodigy, Preston began playing piano at age 3, was performing as an organist by age 10 for gospel singers such as Mahalia Jackson and touring with Little Richard at age 16. He became widely acknowledged as the “Fifth Beatle” having been the only party to ever have his name included in the label credits of the Beatles “Let It Be” and the “Abbey Road” albums as well as the landmark “White Album.” As a solo artist, Preston had a string of Number 1 hit singles including the Grammy-winning “Outta Space,” “Will It Go Round In Circles,” “Nothing From Nothing” and “Space Race.” He wrote the song “You Are So Beautiful” which was a

multi-platinum hit for British blues singer Joe Cocker.

Sept. 4

Multi-platinum, Grammy Award-winning singer Beyoncé Knowles was born on this day in 1981 in Houston. Knowles rose to fame as the creative force and lead singer of R&B girl group Destiny’s Child, the best-selling female group of all time, with over fifty million records sold. The multi-talented Knowles is also an dancer, actress, producer, fashion designer and model, and was twice-nominated for Golden Globe Awards for her performance in “Dream Girls” in 2006. In 2008, she married hip hop mogul Jay-Z and in 2013 was ranked by Forbes magazine among the most powerful celebrities in the world.

Sept. 5

Football player Jerry LeVias was born on this day in 1946 in Beaumont. LeVias starred as a quarterback at Hebert High School, but became the first black scholarship athlete and second black football player in the Southwest Conference as a wide receiver in 1966 at Southern Methodist University. He was an All-America (athletic and academic) as a senior and twice led the league in receiving and left SMU with numerous school and conference career records. With the Houston Oilers, LeVias was selected to the 1969 American Football League All-Star Team. He is a member of both the Texas Sports Hall of Fame and the College Football Hall of Fame.

Sept. 5

Dr. June Brewer was born in Austin on this day in 1925. Brewer was the first of five African-American women to apply for admission to the University of Texas Graduate School in 1950 after the U.S. Supreme Court‘s ruling on Heman Sweatt‘s admission. She was an English Professor at Huston-Tillotson College for 35 years and was Chairperson of the department, the first Endowed Professor (Karl Downs Professor of Humanities) and Professor Emeritus on retirement. She received a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship to conduct research on black women writers which became her teaching specialty. Brewer served on numerous Austin Independent School District task forces, including one for dropout prevention, and also founded a nonprofit organization, Borders Learning Community, which promoted closing the racial achievement gap, especially raising standardized test scores.

Sept. 5

On this day in 1956, Texarkana Junior College was integrated when Jessalyn Yvonne Gray and Laura Ellis passed aptitude tests and were admitted to the school. Their acceptance set off a chain of violent protests and community-wide death threats against blacks by local white racists. A black-owned service station was blasted with shotgun fire, two crosses were burned and a black man was hanged in effigy hours after the 30-year segregation policy was struck down.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

The beginning of the end: D-Day

In June 1944, Allied forces began their assault not only on the beaches of Normandy, but on Nazism itself. Dubbed Operation Overlord, the amphibious exercise is legendary as the extraction of France from German control and the beginning of the end of Adolph Hitler’s plans for a thousand year reign of his Aryan master race. The death tolls were staggering on the initial day of the operation. Thousands of Americans gave the greatest sacrifice in…(more)

Hidden In Plain Sight

In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote The Souls of Black Folk in which he claimed: “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.” That was 1903. American society is in the last year of the second decade of the twenty-first century, and I wonder if that famous quote still applies. In 1903, Jim Crow dominated every aspect of American life and forced the black community into the shadows. Du Bois used”…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.