While NASA Was Landing on the Moon, Many African-Americans Sought Economic Justice Instead

For those living in poverty, the billions spent on the Apollo program, no matter how inspiring the mission, laid bare the nation’s priorities

Photo: Reverend Ralph Abernathy, flanked by associates, stand on steps of a mockup of the lunar module displaying a protest sign while demonstrating at the Apollo 11 launch. (Bettmann/Contributor)

(Smithsonian) In anticipation of astronaut Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon, an estimated 8,000 New Yorkers gathered in Central Park, eager to celebrate the moment. The New York Times ran a photograph of the crowd glued to the networks’ broadcasts on three giant screens and described the event as “a cross between a carnival and a vigil.” Celebrants came dressed in white, as encouraged by the city’s parks department. Waiting for the big show, they listened to the Musician’s Union orchestra play space-themed music and watched student artists dance in a “Moon Bubble,” illuminated by ultra-violet light.

That same day, about 50 blocks north, another estimated 50,000 people, predominantly African-American, assembled in Harlem for a soul-music showcase in Mount Morris Park headlined by Stevie Wonder, whose “My Cherie Amour” was climbing the Billboard charts. The parks department sponsored this event, too, but the audience was less interested in what was happening in the sky overhead. As the Times reported, “The single mention of the [lunar module] touching down brought boos from the audience.”

The reception in Harlem reflects a broader truth about the Apollo 11 mission and how many black communities viewed it. NASA’s moonshot was costly; author Charles Fishman called it “the largest non-military effort in human history” in a recent interview with NPR. Black publications like the New York Amsterdam News and civil rights activists like Ralph Abernathy argued that such funds—$25.4 billion, in 1973 dollars— would be better spent alleviating the poverty facing millions of African-Americans. (more)

Related:

— A complete list of NASA’s African-American astronauts

— A Texan was the first black astronaut to walk in space — Dr. Bernard Harris

The Chicago Defender, Legendary Black Newspaper, Prints Last Copy

For generations of black Americans, The Defender, influential and tough, was a force: “You knew it didn’t happen if it wasn’t in The Defender.”

A newsboy selling The Chicago Defender in 1942. The newspaper is suspending its print operations, though the digital operation continues. (Photo Credit: Jack Delano/Farm Security Administration, via Library of Congress)

(New York Times) Decade by decade, the newspaper told the story of black life in America. It took note of births and deaths, of graduations and weddings, of everything in between. Through eras of angst, its reporters dug into painful, dangerous stories, relaying grim details of lynchings, of clashes over school integration and of the shootings of black men by white police officers. Among a long list of distinguished bylines: Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks.

After more than a century, The Chicago Defender will cease its print editions after Wednesday (July 10), the newspaper’s owner has announced. The Defender will continue its digital operation, according to Hiram E. Jackson, chief executive of Real Times Media, which owns The Defender and other black newspapers around the country. He said the move would allow the news organization to adapt to a fast-changing, highly challenging media environment that has upended the entire newspaper industry.

“It is an economic decision,” Mr. Jackson said, “but it’s more an effort to make sure that The Defender has another 100 years.” (more)

A&M professor wins grant to preserve historic African American settlements

(KBTX-TV) A Texas A&M professor won a national contest for a grant that will help continue her work to protect Texas’s endangered, historic African-American communities.

Andrea Roberts is an assistant professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University and founder of the Texas Freedom Colonies Project. She has been selected as a recipient of a $50,000 grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Roberts joined First News at Four to discuss her work.

Begun by Roberts in 2014, the Texas Freedom Colonies Project is an effort to preserve the history of African American settlements, particularly those founded right after the Civil War until 1930.

“This was a significant time where African Americans were able to create their own communities, even in the shadow of violence and all types of problems,” said Roberts. “They were still able to create these communities throughout Texas.”

The grant money will help Roberts continue this search for information on these communities, ones that generally aren’t in history books or on maps. She researches a different way.

“Basically listening to people,” said Roberts. “We record a lot of oral histories, and I spend a lot of time at homecomings and reunions and different church events–just spending time in these communities.”

Roberts calls the stories “endangered,” saying that this research is urgent.

“The people who know how these places started, know where the cemeteries are, are leaving us; they’re 70, 80, 90 years old,” Roberts said. “These are places that were founded in areas that are susceptible to hurricanes because they were in bottomland–land nobody else wanted.”

Click here or on image for complete interview video.

Austin Public Library: They Took an Oath, Traveling Exhibit

June 15, 2019 – August 25, 2019

Central Library, Shared Learning Room 531, Floor 5 | 710 W. César Chávez St.

Austinite Larry Thomas’ exhibition They Took an Oath showcases the ongoing effort to commemorate the 19th Century Texas Black Legislators and Constitutional Convention Delegates through a traveling exhibit focusing on their 19th Century Legislations. The exhibit is part of the 19th Century Black Legislators’ Monument project unveiled at the Texas State Cemetery, March 2010.

This exhibition, for which Thomas is the curator, is dedicated to these brave, courageous and often forgotten men of Texas and World History. This remarkable exhibit is from original legislative bills, House & Senate Journals and other legislative documents courtesy of the Texas State Library & Archives Commission and the Texas Legislative Reference Library, They Took An Oath, Traveling Exhibit.

For more information, contact the exhibitor at 512-517-9458.

Images courtesy of: Texas State Library & Archives Commission

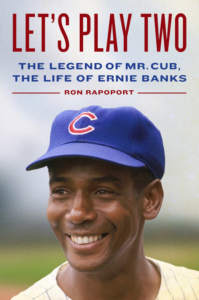

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Let’s Play Two, The Legend of Mr. Cub, The Life of Ernie Banks,” by Ron Rapoport.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Let’s Play Two, The Legend of Mr. Cub, The Life of Ernie Banks,” by Ron Rapoport.

The definitive and revealing biography of Chicago Cubs legend Ernie Banks, one of America’s most iconic, beloved, and misunderstood baseball players, by acclaimed journalist Ron Rapoport.

Ernie Banks, the first-ballot Hall of Famer and All-Century Team shortstop, played in fourteen All-Star Games, won two MVPs, and twice led the Major Leagues in home runs and runs batted in. He outslugged Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Mickey Mantle when they were in their prime, but while they made repeated World Series appearances in the 1950s and 60s, Banks spent his entire career with the woebegone Chicago Cubs, who didn’t win a pennant in his adult lifetime.

Today, Banks is remembered best for his signature phrase, “Let’s play two,” which has entered the American lexicon and exemplifies the enthusiasm that endeared him to fans everywhere. But Banks’s public display of good cheer was a mask that hid a deeply conflicted, melancholy, and often quite lonely man. Despite the poverty and racism he endured as a young man, he was among the star players of baseball’s early days of integration who were reluctant to speak out about Civil Rights. Being known as one of the greatest players never to reach the World Series also took its toll. At one point, Banks even saw a psychiatrist to see if that would help. It didn’t. Yet Banks smiled through it all, enduring the scorn of Cubs manager Leo Durocher as an aging superstar and never uttering a single complaint.

“Let’s Play Two” is based on numerous conversations with Banks and on interviews with more than a hundred of his family members, teammates, friends, and associates as well as oral histories, court records, and thousands of other documents and sources. Together, they explain how Banks was so different from the caricature he created for the public. The book tells of Banks’s early life in segregated Dallas — where he attended Booker T. Washington High School (a member of the Prairie View Interscholastic League) and starred in football, basketball, and track (the school did not have a baseball team!), his years in the Negro Leagues, and his difficult life after retirement; and features compelling portraits of Buck O’Neil, Philip K. Wrigley, the Bleacher Bums, the doomed pennant race of 1969, and much more from a long-lost baseball era.

This Week in Texas Black History

Jul 15

Forest Whitaker, actor, producer, and director, was born on this day in 1961 in Longview. At age four, he moved with his family to Los Angeles. Whitaker was a star tackle at Palisades High School and received college football scholarship offers, however, after suffering a back injury he began to study opera and acting. In 1982, he made his film debut in the comedy Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but his breakout role came in 1988 portraying jazz legend Charlie Parker, in the Clint Eastwood film, Bird, for which Whitaker earned the Cannes Film Festivalaward for Best Actor and a Golden Globe nomination. His first directing effort was the film Waiting to Exhale in 1995, and in 2006 was widely lauded for his role as Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in the movie The Last King of Scotland. For that, Whitaker earned the 2007 Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, making him the fourth African-American actor to do so, joining Sidney Poitier, Denzel Washington, and Jamie Foxx. That same year, Whitaker played Dr. James Farmer Sr. in The Great Debaters, the movie about the acclaimed Wiley College debate team of the 1930s and its coach, Melvin Tolson.

Jul 16

On this date in 1929, Wilhelmina Delco was born in Chicago. Delco received a degree in sociology from Fisk University in Nashville in 1950 and seven years later relocated with her husband to Austin. Delco was elected to the Austin Independent School District Board of Trustees in 1968, making her the first African American elected to public office in Austin. In 1974, she won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives, making her the first African American official elected at-large in Travis County. Delco served 10 terms in the Legislature. In 1991, she was appointed Speaker Pro Tempore, becoming the first woman and the second African American to hold the second highest position in the Texas Houseof Representatives. She retired from the Legislature in 1995.

Jul 20

On this day in 1910, Galveston native Jack Johnson was recognized as the heavyweight champion of the world. He had won the Negro heavyweight championship in 1903. The reigning white champion, Jim Jeffries, refused to cross the color line, so Johnson had to wait until Jeffries came out of retirement to fight him in 1910. Johnson left the United States in 1913 to avoid arrest on charges of violation of the Mann Act. When he returned on July 20, 1920, he was arrested and jailed at Leavenworth. After his release he returned to boxing, but without success. He died in an automobile crash at Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1946.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

A community under siege: the Summer of 1919

One hundred years ago this country basked in the light of victory over fascism, that political system which seemingly posed a direct threat to the ideals of democracy. Supposedly, citizens in a democratic society would be able to advance socially and economically as far as their talents would take them. I guess the operative word is “citizen”…(more)

Death is nothing at all

“Therefore we are always confident, knowing that, whilst we are at home in the body, we are absent from the Lord: (For we walk by faith, not by sight:). We are confident, I say, and willing rather to be absent from the body, and to be present with the Lord.” 2 Cor 5: 6-8. As a child my father and I would watch “Hogan’s Heroes.” It’s a silly sitcom, but I remember how I enjoyed…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.