The Tyler Rose: The Story of UT’s Recruitment of Earl Campbell

(Alcalde) In 1973, Darrell K Royal faced challenges landing top African-American high school football players, so he enlisted a team of recruiters. Led by Ken Dabbs, they set out to convince the state’s top running back, Tyler’s Earl Campbell, that The University of Texas was where he needed to be. In an excerpt from journalist Asher Price’s forthcoming book, “Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact,” Royal, Dabbs, and their crew show Earl—and his mother, Ann—that the Longhorns would give him the best chance to succeed, on the field and off.

In mid-August 1973, seven years after Darrell K Royal had told Ken Dabbs, then an assistant coach in a small Texas town, that he was not ready to offer a scholarship to one of his African-American players—no black players would appear on the Longhorns varsity until 1970—Royal tracked him down to ask him for a peculiar kind of help.

It was nearly 1 p.m. on a Sunday, a couple of hours after church. Dabbs was by then the head coach at the new football program at Westlake High, in a fast-growing suburb on Austin’s western fringe, and Royal, one of the most famous coaches in America, asked Dabbs to come by his house. “I was nervous, I was scared, but I went over there,” Dabbs said. Royal offered him a job as freshman backfield coach—and then he asked Dabbs, who is white, to recruit in East Texas and South Dallas, areas with high concentrations of African Americans.

“And he asked me, ‘Do you have any questions?’ And I said, ‘Yes, sir, I have one: When you can hire anybody in the United States of America, why would you hire a nobody coach from Westlake?’”

“I’ll be real honest with you,” Royal told him. “If I had listened to you in 1966, I wouldn’t be in the mess I’m in now.” (more)

‘A Walk On The River’ Documents African American History In San Antonio

(Texas Public Radio — The Source) Historical narratives often overlook the contributions of African Americans. The film “A Walk on the River- A Black History of the Alamo City” chronicles San Antonio’s robust black history through interviews with historians, activists and private citizens.

(Texas Public Radio — The Source) Historical narratives often overlook the contributions of African Americans. The film “A Walk on the River- A Black History of the Alamo City” chronicles San Antonio’s robust black history through interviews with historians, activists and private citizens.

Two years after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, slaves in Texas learned of their freedom. That day was June 19, 1865. Today, the holiday is known and celebrated as Juneteenth.

“A Walk on the River” highlights black communities, churches, and businesses in the Alamo City from Juneteenth to present day.

What can we learn from San Antonio’s African American history? How did black communities survive during segregation and beyond? How will these stories inform future generations?

More: Audio interview and movie trailer

Otis Williams: ‘The Temptations didn’t love themselves’

The only surviving original member of the hit R&B group talks about the darker side of a legacy and the musical it inspired

David Ruffin, Melvin Franklin, Paul Williams, Otis Williams and Eddie Kendricks of the Temptations pose for a portrait in 1965. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

(The Guardian) One of the first times Otis Williams, the founder and last surviving original member of the Temptations, realized his music made an indelible impact on their fans occurred after he received a letter in the mail. “I’m reading it and it said to give them a call the first chance I had,” Williams remembers. “She gets on the phone and told me she was ill and asked: ‘God, don’t take me until I speak to Otis Williams.’ She said she wanted to tell me how much the music meant to her before she died. I didn’t have any idea when we started making this music to just have fun and make money that it’d be so emotional for people.”

It’s a sentiment that has lasted through the Temptations’ success, as they have held onto the distinction of being one of the most commercially dominant vocal groups in music history. With 14 R&B No 1 singles under their belts (among them: My Girl, The Way You Do the Things You Do, Cloud Nine, Papa Was a Rolling Stone and Get Ready), their music provided a soundtrack to the 60s and early 70s, helping lift up Motown Records in the process.

Despite launching over a half-century ago, the Temptations and their legend has lately been enjoying fresh relevance. A jukebox musical, based on their rise and told from the perspective of Williams dubbed Ain’t Too Proud (named after their 1966 signature Ain’t Too Proud to Beg) debuted on Broadway in March and later garnered 11 Tony nominations, winning for best choreography. In addition, Williams — a native of Texarkana, Texas — was recently honored at the Apollo Theater’s recent Spring Gala where he was bestowed a spot on the historic Harlem theater’s Walk of Fame. “Here I am, 77 years old and I’m enjoying my life as if I’m 27,” Williams says to the Guardian. “I am profoundly blessed to be doing what I’m doing 59 years later.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

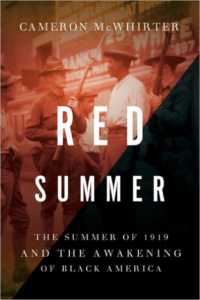

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America,” by Cameron McWhirter.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America,” by Cameron McWhirter.

A narrative history of America’s deadliest episode of race riots and lynchings.

After World War I, black Americans fervently hoped for a new epoch of peace, prosperity, and equality. Black soldiers believed their participation in the fight to make the world safe for democracy finally earned them rights they had been promised since the close of the Civil War.

Instead, an unprecedented wave of anti-black riots and lynchings swept the country for eight months. From April to October of 1919, the racial unrest rolled across the South into the North and the Midwest, even to the nation’s capital. Millions of lives were disrupted, and hundreds of lives were lost. Blacks responded by fighting back with an intensity and determination never seen before.

Red Summer is the first narrative history written about this epic encounter. Focusing on the worst riots and lynchings—including those in Chicago; Washington, D.C.; Longview, TX; and St. Louis—Cameron McWhirter chronicles the mayhem, while also exploring the first stirrings of a civil rights movement that would transform American society forty years later.

This Week in Texas Black History

Jul 11

On this day in 1828, Rev. John Henry “Jack” Yates was born into slavery in Gloucester County, Virginia. He moved with his wife (Harriet) and 11 children in 1863 when Harriet’s master relocated with his slaves to Matagorda County. Following emancipation in 1865, Yates moved his family to Houston where he began working with the Home Missionary Society and was ordained a Baptist minister. In 1866, after being ordained, Yates became the first pastor of Antioch Baptist Church, the first black Baptist church in Houston. Yates was also active in education, volunteering Antioch as the site for a Freedmen’s Bureau school and he also helped bring the first Baptist college to Texas, Bishop Academy, an institution that prepared students for employment in trades, business and ministry. Houston’sJack Yates High School, built in 1926, is named in his honor.

Jul 11-12

On these days in 1919 the Longview Race Riot occurred, precipitated by an article in the July 10 issue of the Chicago Defender describing the death of a young black man, Lemuel Walters, in Longview. The article, written by Longview teacher Samuel L. Jone, reported that Walters and an unnamed white woman from Kilgore were in love and quoted her as saying they would have married if they had lived in the North. Walters, according to the article, was safely locked in the Gregg County Jail until the sheriff willingly handed him over to a white mob that murdered him on June 17. Jones was held responsible for the article, and on July 10 was accosted and beaten, supposedly by two brothers of the Kilgore woman. News of the article and of the attack on Jones inflamed tempers of both races, and on July 11, a group of twelve to fifteen angry white men drove to Jones’s house where they engaged in a gunfight with residents of the house. Some of the white men went to the fire station and rang the alarm to attract more recruits; others broke into a hardware store to get guns and ammunition. A white mob burned several black homes and a dance hall. Governor William P. Hobby sent Texas Rangers and National Guardsmen to Longview and placed the city and county under martial law. The rangers arrested seventeen white men on charges of attempted murder. Twenty-one black men were arrested, charged, and sent to Austin temporarily for their own safety. Nine white men were also charged with arson. None of the whites or blacks was ever tried.

On these days in 1919 the Longview Race Riot occurred, precipitated by an article in the July 10 issue of the Chicago Defender describing the death of a young black man, Lemuel Walters, in Longview. The article, written by Longview teacher Samuel L. Jone, reported that Walters and an unnamed white woman from Kilgore were in love and quoted her as saying they would have married if they had lived in the North. Walters, according to the article, was safely locked in the Gregg County Jail until the sheriff willingly handed him over to a white mob that murdered him on June 17. Jones was held responsible for the article, and on July 10 was accosted and beaten, supposedly by two brothers of the Kilgore woman. News of the article and of the attack on Jones inflamed tempers of both races, and on July 11, a group of twelve to fifteen angry white men drove to Jones’s house where they engaged in a gunfight with residents of the house. Some of the white men went to the fire station and rang the alarm to attract more recruits; others broke into a hardware store to get guns and ammunition. A white mob burned several black homes and a dance hall. Governor William P. Hobby sent Texas Rangers and National Guardsmen to Longview and placed the city and county under martial law. The rangers arrested seventeen white men on charges of attempted murder. Twenty-one black men were arrested, charged, and sent to Austin temporarily for their own safety. Nine white men were also charged with arson. None of the whites or blacks was ever tried.

Jul 12

Texas Congresswoman, Barbara Jordan, became the first African-American to give the keynote address at a major national political convention by giving a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention on this date in 1976 in New York City. In opening her remarks, Jordan noted the significance of her appearance: “…my presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American dream need not ever be deferred.” Jordan was a Houston native and graduate of Phillis Wheatley High School and Texas Southern University.

Texas Congresswoman, Barbara Jordan, became the first African-American to give the keynote address at a major national political convention by giving a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention on this date in 1976 in New York City. In opening her remarks, Jordan noted the significance of her appearance: “…my presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American dream need not ever be deferred.” Jordan was a Houston native and graduate of Phillis Wheatley High School and Texas Southern University.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

A community under siege: the Summer of 1919

One hundred years ago this country basked in the light of victory over fascism, that political system which seemingly posed a direct threat to the ideals of democracy. Supposedly, citizens in a democratic society would be able to advance socially and economically as far as their talents would take them. I guess the operative word is “citizen”…(more)

Death is nothing at all

“Therefore we are always confident, knowing that, whilst we are at home in the body, we are absent from the Lord: (For we walk by faith, not by sight:). We are confident, I say, and willing rather to be absent from the body, and to be present with the Lord.” 2 Cor 5: 6-8. As a child my father and I would watch “Hogan’s Heroes.” It’s a silly sitcom, but I remember how I enjoyed…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.