Houston’s Oldest Park Debuts Its $33.6 Million Renovation

Although Emancipation Park informally opened at the beginning of the year, the Juneteenth Festival will mark its grand reopening.

(Photo: The park’s new recreation center)

Emancipation Park opened in the Third Ward in 1872, on a plot of land purchased for $800 by a group of former slaves. The opening took place nine years after president Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and seven years after slaves were formally freed in Texas.

The park became the first truly public park in Houston, and a vital community hub in the historically African-American neighborhood. But during the ’60s, it fell into disrepair, the result of the new I-59, which bifurcated the area, and a population that scattered following desegregation.

Fast-forward to 10 years ago. The community formed Friends of Emancipation Park—now Emancipation Park Conservancy Inc. To preserve the park’s legacy, they partnered with the Kinder Foundation, Houston Endowment and H-E-B, among other backers, as well as neighborhood and citywide leaders, and got to work.

Ramon Manning—TSU grad, energy executive, longtime Third Ward resident, and board chairman of the conservancy since 2014—says that renovating the park took a village, and adds that he looks forward to its lasting impact on the community. “The park was founded by freed slaves and speaks to the foresight and mindset of today,” he says. “It’s thrilling to make the Third Ward a cultural destination.”

Related: Mayor Turner to Host Juneteenth Parade & Emancipation Park Rededication Celebration

She became the first black woman to win an NCAA Division I tennis singles title, and she had no idea

Brienne Minor: “I didn’t even realize it until my sister said something to me a couple days later.” (Richard Hamm/Associated Press)

The woman wearing maize and blue celebrated her moment knowing she had made history, but not quite knowing the full extent of the story.

When her opponent’s forehand down the line finally floated long, Brienne Minor simply offered a joyful, graceful toss of her racket, a double fist-pump at shoulder level and a single clap in front of her chest. Then off to the net to shake hands. She kept her head down for the first few steps — best not to smile too big in front of the runner-up.

Minor had always been quiet and humble, the third in a line of tennis-playing sisters from Mundelein, Ill., a suburb of Chicago. But if she ever had a reason to lose her composure, to rip the neatly knotted bun at the nape of her neck loose and really go berserk, it would have been on that muggy Monday last month in Georgia when Minor captured the NCAA singles title and became Michigan’s first national champion in the sport.

The 19-year-old is the first African American woman to win an NCAA Division I singles championship. She is the first black player to win a Division I singles title for either men or women since Arthur Ashe in 1965. (more)

What Hattie McDaniel Said About Her Oscar-Winning Career Playing Racial Stereotypes

Hattie McDaniel is remembered as the first black actor to ever win an Oscar.

Hattie McDaniel is remembered as the first black actor to ever win an Oscar.

But McDaniel, born June 10, 1895 in Wichita, Kansas, was far more than that. In total, McDaniels played a maid at least 74 times over her career, perhaps most notably in her Oscar-winning performance as Mammy, Scarlett O’Hara’s slave and best counselor in Gone With the Wind. Her character’s name was the one used for many black female slaves who took on domestic roles.

McDaniels was lauded for her performance as Mammy—a performance that continued off-screen as well. She was credited as “Hattie ‘Mammy’ McDaniel” in the film, did a tour of Gone With the Wind showings in costume. She even auditioned for the part in costume.

But she was also criticized by the NAACP for portraying stereotypes on screen. In 1947, McDaniels published an article in which she personally addressed her critics in Hollywood Reporter, writing, in part, “I have never apologized for the roles I play.” (more)

First Renovations To Austin’s Historic Downs Field Deemed A Home Run; marker unveiled

Standing a few yards from first base in an East Austin ballpark, City Council Member Ora Houston recounted her earliest memories of the diamond.

Standing a few yards from first base in an East Austin ballpark, City Council Member Ora Houston recounted her earliest memories of the diamond.

“When I was 4 or 5 years old, I was a junior cheerleader on this park at the baseball games of Sam Huston College,” she said.

Houston joined city officials and community members on June 10 to celebrate the completion of the first of several renovations to Downs Mabson Field. In the early 20th century, the field was home to the Austin Black Senators, a Negro League team. It also still serves as home field for Huston-Tillotson University.

Also during the ceremonies, a historical marker was unveiled. (more, including audio)

TIPHC Bookshelf

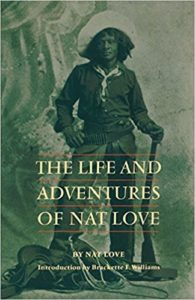

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Life and Adventures of Nat Love,” by Nat Love.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Life and Adventures of Nat Love,” by Nat Love.

Thousands of black cowpunchers drove cattle up the Chisholm Trail after the Civil War, but only Nat Love wrote about his experiences. Born to slaves in Davidson County, Tennessee, the newly freed Love struck out for Kansas after the war. He was fifteen and already endowed with a reckless and romantic readiness. In wide-open Dodge City he joined up with an outfit from the Texas Panhandle to begin a career riding the range and fighting Indians, outlaws, and the elements. Years later he would say, “I had an unusually adventurous life.”

That was rare understatement. More characteristic was Love’s claim: “I carry the marks of fourteen bullet wounds on different parts of my body, most any one of which would be sufficient to kill an ordinary man, but I am not even crippled.” In 1876 a virtuoso rodeo performance in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, won him the moniker of Deadwood Dick. He became known as DD all over the West, entering into dime novels as a mysteriously dark and heroic presence. This vivid autobiography includes encounters with Bat Masterson and Billy the Kid, a soon-after view of the Custer battlefield, and a successful courtship. Love left the range in 1890, the year of the official closing of the frontier. Then, as a Pullman train conductor he traveled his old trails, and those good times bring his story to a satisfying end.

This Week In Texas Black History, June 11-17

11 — On this day in 1991, Connie Yerwood died in Austin. In 1937, she became the first African American doctor to work for Texas Public Health Services. The Victoria native would also become the first black director of Maternal and Child Services in Texas and the first black chief of the Bureau of Personal Health Services. Yerwood was a long-time trustee of Samuel Huston College and the national president of its National Alumni Association.

11 — On this day in 1991, Connie Yerwood died in Austin. In 1937, she became the first African American doctor to work for Texas Public Health Services. The Victoria native would also become the first black director of Maternal and Child Services in Texas and the first black chief of the Bureau of Personal Health Services. Yerwood was a long-time trustee of Samuel Huston College and the national president of its National Alumni Association.

12 — James Leonard Farmer, Sr., who normally wrote his name “J. Leonard Farmer” on all of his publications, was born on this date in Kingstree, South Carolina in 1886. Farmer became Texas’ first black professor with an earned Ph.D (Boston University 1918), pastored churches in Texarkana, Marshall and Galveston and taught at Wiley College in Marshall (1919-20 and 1934-39) and Samuel Huston (later Huston-Tillotson) (1925-30 and 1946-56), in Austin. His son, James Farmer, Jr., was a noted Civil Rights activist and founder of CORE and was one of Wiley’s “Great Debaters.”

12 — James Leonard Farmer, Sr., who normally wrote his name “J. Leonard Farmer” on all of his publications, was born on this date in Kingstree, South Carolina in 1886. Farmer became Texas’ first black professor with an earned Ph.D (Boston University 1918), pastored churches in Texarkana, Marshall and Galveston and taught at Wiley College in Marshall (1919-20 and 1934-39) and Samuel Huston (later Huston-Tillotson) (1925-30 and 1946-56), in Austin. His son, James Farmer, Jr., was a noted Civil Rights activist and founder of CORE and was one of Wiley’s “Great Debaters.”

14 – In 1854, on this date, famous cowboy Nat Love, “Deadwood Dick,” was born as a slave on Robert Love’s plantation in Davidson County Tennessee. (Nat is pronounced “Nate.”) Love became proficient at breaking horses, and at age 15, headed west with $50 in his pocket to seek work as a cowboy. In Dodge City, Kansas, he met the crew of the Duval Ranch at the conclusion of their cattle drive and returned with them to Texas to work at the ranch. The teenager quickly adapted to cowboy life and excelled as a ranch hand and a marksman with his .45 revolver. He earned the name, “Deadwood Dick,” after winning an all-around cowboy contest in Deadwood, S.D. The contestants competed in roping, bridling, saddling, and shooting and Love finished first in each category, walking away with the $200 prize and a new nickname.

14 – In 1854, on this date, famous cowboy Nat Love, “Deadwood Dick,” was born as a slave on Robert Love’s plantation in Davidson County Tennessee. (Nat is pronounced “Nate.”) Love became proficient at breaking horses, and at age 15, headed west with $50 in his pocket to seek work as a cowboy. In Dodge City, Kansas, he met the crew of the Duval Ranch at the conclusion of their cattle drive and returned with them to Texas to work at the ranch. The teenager quickly adapted to cowboy life and excelled as a ranch hand and a marksman with his .45 revolver. He earned the name, “Deadwood Dick,” after winning an all-around cowboy contest in Deadwood, S.D. The contestants competed in roping, bridling, saddling, and shooting and Love finished first in each category, walking away with the $200 prize and a new nickname.

15-16 – On these days in 1943, the Beaumont Riots occurred. Conditions in the city were already tense because blacks and whites were competing for jobs in the shipyards because of World War II and because of a lack of enough resources, traditionally segregated facilities were forced to integrate. The situation escalated when a white woman reported being raped by a black man, though she was unable to identify the suspect being held at the city jail. However, on the evening of June 15 more than 2,000 workers, plus perhaps another 1,000 interested bystanders, marched toward City Hall, then dispersed into small bands and began breaking into stores in the black section of downtown Beaumont. With guns, axes, and hammers, they proceeded to terrorize black neighborhoods in central and north Beaumont. Many blacks were assaulted, several restaurants and stores were pillaged, a number of buildings were burned, and more than 100 homes were ransacked. More than 200 people were arrested, fifty were injured, and two – one black and one white – were killed. Another black man died several months later of injuries received during the riot. Beaumont was among several U.S. cities that experienced violent race riots that summer, including Detroit, Harlem, and Mobile, Ala.

15-16 – On these days in 1943, the Beaumont Riots occurred. Conditions in the city were already tense because blacks and whites were competing for jobs in the shipyards because of World War II and because of a lack of enough resources, traditionally segregated facilities were forced to integrate. The situation escalated when a white woman reported being raped by a black man, though she was unable to identify the suspect being held at the city jail. However, on the evening of June 15 more than 2,000 workers, plus perhaps another 1,000 interested bystanders, marched toward City Hall, then dispersed into small bands and began breaking into stores in the black section of downtown Beaumont. With guns, axes, and hammers, they proceeded to terrorize black neighborhoods in central and north Beaumont. Many blacks were assaulted, several restaurants and stores were pillaged, a number of buildings were burned, and more than 100 homes were ransacked. More than 200 people were arrested, fifty were injured, and two – one black and one white – were killed. Another black man died several months later of injuries received during the riot. Beaumont was among several U.S. cities that experienced violent race riots that summer, including Detroit, Harlem, and Mobile, Ala.

15 – On this date in 1921, Bessie Coleman, from Atlanta, Texas, became the first licensed black pilot in the world when she earned an international aviation license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. As a barnstorming stunt pilot, she became known as “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie.” In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bessie’s honor and in 2000 she was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. The main road to Atlanta’s airport is named Bessie Coleman Drive.

15 – On this date in 1921, Bessie Coleman, from Atlanta, Texas, became the first licensed black pilot in the world when she earned an international aviation license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. As a barnstorming stunt pilot, she became known as “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie.” In 1995, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bessie’s honor and in 2000 she was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. The main road to Atlanta’s airport is named Bessie Coleman Drive.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “100 days,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.