The black history of Memorial Day has been nearly wiped from public memory — here’s the real story

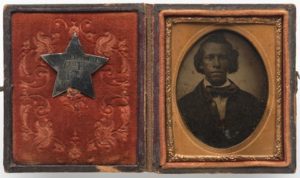

(Photo: 107th U.S. Colored Infantry at Fort Corcora (Library of Congress)

Union General John Logan is often credited with founding Memorial Day. The commander-in-chief of a Union veterans’ organization called the Grand Army of the Republic, Logan issued a decree establishing what was then named “Decoration Day” on May 5, 1868, declaring it “designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

Today, cities across the North and South claim credit for establishing the first Decoration Day—from Macon, Georgia to Richmond, Virginia to Carbondale, Illinois. Yet, a key story of the holiday has been nearly erased from public memory and most official accounts, including that offered by the the Department of Veterans Affairs.

During the spring of 1865, African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina—most of them former slaves—held a series of memorials and rituals to honor unnamed fallen Union soldiers and boldly celebrate the struggle against slavery. One of the largest such events took place on May first of that year but had been largely forgotten until David Blight, a history professor at Yale University, found records at a Harvard archive. In a New York Times article published in 2011, Blight described the scene. While it is difficult to pinpoint the precise birthplace of the holiday, it is fair to say that ceremonies like the following are largely erased from the American narrative of Memorial Day. (more)

Literary: Black Soldiers — Fighting America’s Enemies Abroad and Racism at Home

Tintype of Creed Miller with star-shaped military identification pin, 107th Regiment. 1864.Credit Smithsonian National Museum of History and Culture

After visiting Fort Hood Army base in Texas, the journalist Ray Suarez observed that as much as it represented a separate military culture, with distinct rules and protocols, it was also a microcosm of the nation. “One of the most attractive aspects of the people I met at Fort Hood was their very ordinariness,” Mr. Suarez wrote in 2010. “They are tall, short, men, women, rural, urban, skinny, buffed, chubby, provincial, worldly, with accents and life experience from every corner of the country.”

And for much of its existence, the U.S. military mirrored the nation in another, less auspicious way: its sanctioning of racial segregation. “Double Exposure: Fighting for Freedom,” published by D Giles Limited in association with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, documents the complex history of black soldiers, illuminating their triumphs and challenges.

The fifth volume in the museum’s Double Exposure series, “Fighting for Freedom” presents more than 50 works from its photography collection that exemplify the bravery, patriotism and dignity of African-American men and women in uniform. While black participation in the military dates back to the Revolutionary War, the book spans the history of African-American service from the Civil War to Iraq. In addition to the short texts that accompany many photographs, the book includes essays by the museum’s director, Lonnie G. Bunch III, the retired Marine Maj. Gen. Charles F. Bolden Jr. and the journalist Gail Lumet Buckley. (more)

A military cemetery whose African American history is hidden in plain sight

Walking with World War II vet Benjamin Berry (left), Ed McLaughlin is trying get the V.A. to erect a storyboard about the 1,000 African American Civil War soldiers who are buried in a segregated corner of Philadelphia National Cemetery. DAVID SWANSON / Staff Photographer

Of the 11,500 veterans and family members buried in Philadelphia National Cemetery, many were African American soldiers, for the most part interred in segregated sections of the cemetery. At least 350 were U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) who fought in the Civil War and trained at Camp William Penn in Cheltenham, the first such facility for black enlistees in the Union Army.

Nearly two years ago, the VA National Cemetery Administration erected three storyboards highlighting the graveyard’s significance. One was about the cemetery, the oldest of four national cemeteries in the Philadelphia region. Another was about Valley Forge native Galusha Pennypacker, who at age 20 became the youngest person ever to hold the rank of brigadier general. The last was dedicated to 184 Confederate soldiers buried there after being wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg and dying in area hospitals.

There was none for the U.S. Colored Troops.

An embarrassing oversight, declared Ed McLaughlin. A 74-year-old Army veteran from Flourtown and retired satellite designer for Lockheed Martin, he and a corps of supporters have been fighting ever since to set it right.

McLaughlin already knew all about the cemetery and its unheralded history. A genealogy buff who frequently visited Philadelphia National to research his family, he had seen the USCT graves, recognizable by the acronym engraved on the headstones.

“I realized the enormity of it,” he said. “This is important. This is an historical treasure. It has to be known.” (more)

Ellis County African American Hall of Fame receives honor award from Preservation Texas

(Waxahachie Daily Light) Within the walls of the Ellis County African American Hall of Fame is the rarely told history of segregation and its transformation into amalgamation.

(Waxahachie Daily Light) Within the walls of the Ellis County African American Hall of Fame is the rarely told history of segregation and its transformation into amalgamation.

This hall of fame is one of the few institutional structures remaining in East Waxahachie on the corner of Martin Luther King Boulevard and Wyatt Street, situated about five blocks from the Ellis County Courthouse Square.

“Waxahachie is considered one of the most historic towns in Texas,” explained Ellen Beasley, architectural historian and preservationist. “However, very little is documented about its African American community.”

One of nineteen genuine restoration and rehabilitation projects recognized by Preservation Texas, the Ellis County African American Hall of Fame stands as a historical beacon through Ellis County’s racial discrimination-era. One of nineteen genuine restoration and rehabilitation projects recognized by Preservation Texas, the Ellis County African American Hall of Fame stands as a historical beacon through Ellis County’s racial discrimination-era. (more)

Texas Town ‘Balances’ Confederate Statue With One Of Lawyer Who Fought KKK

(NPR) Arguments over Confederate statuary and flags rage on across the South. Confederate memorials in Norfolk and St. Louis were vandalized, the small town of Brandenburg, Ky. welcomed a Confederate statue that the University of Louisville had taken down and New Orleans has now removed four monuments. Controversies have also sprouted in Virginia, South Carolina and Maryland.

The debate over monuments usually centers around one question — should they stay or should they go? Now, some leaders of a town in Texas with their own controversial confederate statue believe they’ve found a third option — though not everyone is thrilled with their compromise.

Georgetown Mayor Dale Ross stands in his historic town square, hand resting proudly on the chest of Dan Moody, the city’s latest statuaries acquisition.

“He is an icon in Williamson County. He was responsible for the first successful prosecution of the KKK in the United States of America,” Ross explained. However, the town’s black residents note that Moody means little to nothing to people of color in Williamson County, and that, as governor, he tried to prohibit African-Americans from voting in the Texas Democratic primary, arguing the party was like a private club and therefore could keep black voters out. (more, including audio broadcast)

“Exploring Texas Freedom Colonies Symposium”

TIPHC Bookshelf

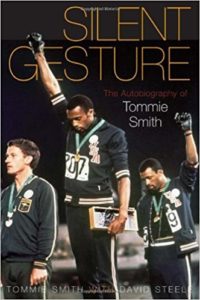

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Silent Gesture, The Autobiography of Tommie Smith,” by Tommie Smith with David Steele.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Silent Gesture, The Autobiography of Tommie Smith,” by Tommie Smith with David Steele.

At the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, Tommie Smith and his teammate John Carlos came in first and third, respectively, in the 200-meter dash. As they received their medals, each man raised a black-gloved fist, creating an image that will always stand as an iconic representation of the complicated conflations of race, politics, and sports. In this, his autobiography, Smith fills out the story around that moment–how it came to be and where it led him.

Smith engagingly describes his life-long commitment to athletics, education, and human rights. He also dispels some of the myths surrounding his famous gesture of protest: contrary to legend, Smith was not a member of the Black Panthers, nor were his medals taken back by the Olympic Committee. Retelling the fear he felt in planning and carrying out his protest, the death threats against him, his difficulty in finding work, and his determination to live his values, he conveys the long, painful backlash that came with his fame, and his fate, all of which was wrapped up in his “silent gesture.”

This Week In Texas Black History, June 4-10

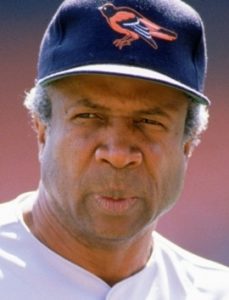

4 — In 1991, on this day, Baltimore Orioles manager Frank Robinson is named assistant general manager of the club, only the third African American to become an assistant GM. As a player with the Orioles, Robinson, a Beaumont native, won the triple crown (leading the league in home runs (49), runs batted in (122), and batting average (.316) in 1966. Robinson began managing the Cleveland Indians in 1975 as the first African American to manage a major league team. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

4 — In 1991, on this day, Baltimore Orioles manager Frank Robinson is named assistant general manager of the club, only the third African American to become an assistant GM. As a player with the Orioles, Robinson, a Beaumont native, won the triple crown (leading the league in home runs (49), runs batted in (122), and batting average (.316) in 1966. Robinson began managing the Cleveland Indians in 1975 as the first African American to manage a major league team. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

5 – On this day in 1950, The U.S. Supreme Court ordered Heman Sweatt admitted to the University of Texas Law School. In handing down its decision in Sweatt v. Painter, the Court concluded that black law students were not offered substantial quality in educational opportunities and that Sweatt could therefore not receive an equal education in a separate law school. Sweatt had teamed with the NAACP to challenge the admissions policy at the UT Law School. The NAACP was looking to test separate but equal education statutes in Texas and the result of Sweatt’s legal battle struck down segregationist policies at the school (for graduate and professional programs only), gained him admission, and paved the way for the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which opened integration for undergraduates.

5 – On this day in 1950, The U.S. Supreme Court ordered Heman Sweatt admitted to the University of Texas Law School. In handing down its decision in Sweatt v. Painter, the Court concluded that black law students were not offered substantial quality in educational opportunities and that Sweatt could therefore not receive an equal education in a separate law school. Sweatt had teamed with the NAACP to challenge the admissions policy at the UT Law School. The NAACP was looking to test separate but equal education statutes in Texas and the result of Sweatt’s legal battle struck down segregationist policies at the school (for graduate and professional programs only), gained him admission, and paved the way for the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which opened integration for undergraduates.

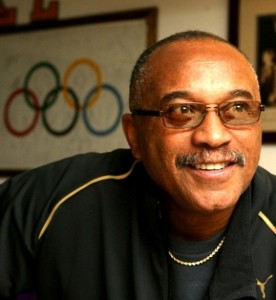

6 – On this day in 1944, Olympic sprint champion Tommie Smith was born in Clarksville. The seventh of 12 children, he survived a life-threatening bout of pneumonia as an infant. Smith is the only man in the history of track and field to hold 11 world records simultaneously. At San Jose State University, he tied or broke 13 world records. However, he is most remembered as one half of the duo of black U.S. Olympians – along with John Carlos – who, during the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, stood on the victory stand with heads bowed and raised clinched fists in a demonstration for human rights, liberation and solidarity. The protest overshadowed Smith’s performance on the track where he broke the world and Olympic records, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter sprint with a time of 19.83 seconds. The story of the “silent gesture” is captured in the 1999 HBO-TV documentary, “Fists of Freedom.” In 1978, Smith was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and has accumulated many other honors.

6 – On this day in 1944, Olympic sprint champion Tommie Smith was born in Clarksville. The seventh of 12 children, he survived a life-threatening bout of pneumonia as an infant. Smith is the only man in the history of track and field to hold 11 world records simultaneously. At San Jose State University, he tied or broke 13 world records. However, he is most remembered as one half of the duo of black U.S. Olympians – along with John Carlos – who, during the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, stood on the victory stand with heads bowed and raised clinched fists in a demonstration for human rights, liberation and solidarity. The protest overshadowed Smith’s performance on the track where he broke the world and Olympic records, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter sprint with a time of 19.83 seconds. The story of the “silent gesture” is captured in the 1999 HBO-TV documentary, “Fists of Freedom.” In 1978, Smith was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and has accumulated many other honors.

7 – On this day in 1950, John Chase enrolled in the University of Texas School of Architecture graduate program, becoming the first African-American to enroll at a major university in the South. Chase, a native of Annapolis, Md., earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first black graduate of the University. That same year, he also became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade. In 1980, he became the first African-American appointed to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts. His firm’s designs include: the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, the Harris County Astrodome Renovation, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University.

7 – On this day in 1950, John Chase enrolled in the University of Texas School of Architecture graduate program, becoming the first African-American to enroll at a major university in the South. Chase, a native of Annapolis, Md., earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first black graduate of the University. That same year, he also became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade. In 1980, he became the first African-American appointed to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts. His firm’s designs include: the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, the Harris County Astrodome Renovation, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University.

9 – On this date in 1965 the University Interscholastic League State Executive Committee validated the Legislative Council’s decision to open league membership to all public schools. The UIL was formed in 1913 with the stipulation that its membership was open only to white schools. In 1920, the Prairie View Interscholastic League was formed as the UIL’s counterpart to govern academic and athletic competitions for the state’s high schools for black students. Black schools began UIL competition in the 1967-68 school year. After the 1969-70 school year, the UIL fully absorbed all PVIL member schools. The PVIL played a leading role in developing African-American students in the arts, literature, athletics and music from the 1920’s through 1970. Among its football stars, alone, were: Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Ernie Ladd (Orange Wallace), and Jerry Levias (Beaumont Hebert).

9 – On this date in 1965 the University Interscholastic League State Executive Committee validated the Legislative Council’s decision to open league membership to all public schools. The UIL was formed in 1913 with the stipulation that its membership was open only to white schools. In 1920, the Prairie View Interscholastic League was formed as the UIL’s counterpart to govern academic and athletic competitions for the state’s high schools for black students. Black schools began UIL competition in the 1967-68 school year. After the 1969-70 school year, the UIL fully absorbed all PVIL member schools. The PVIL played a leading role in developing African-American students in the arts, literature, athletics and music from the 1920’s through 1970. Among its football stars, alone, were: Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Ernie Ladd (Orange Wallace), and Jerry Levias (Beaumont Hebert).

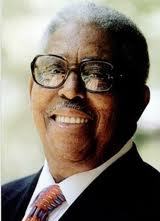

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “100 days,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.