Time Magazine: 100 Photos Collection — The stories behind 100 images that changed the world

Emmett Till, 1955, photograph by David Jackson

“When people saw what had happened to my son, men stood up who had never stood up before.” Mamie Till-Mobley

In August 1955, Emmett Till, a black teenager from Chicago, was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he stopped at Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market. There he encountered Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Whether Till really flirted with Bryant or whistled at her isn’t known. But what happened four days later is. Bryant’s husband Roy and his half brother, J.W. Milam, seized the 14-year-old from his great-uncle’s house. The pair then beat Till, shot him, and strung barbed wire and a 75-pound metal fan around his neck and dumped the lifeless body in the Tallahatchie River. A white jury quickly acquitted the men, with one juror saying it had taken so long only because they had to break to drink some pop. When Till’s mother Mamie came to identify her son, she told the funeral director, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” She brought him home to Chicago and insisted on an open casket. Tens of thousands filed past Till’s remains, but it was the publication of the searing funeral image in Jet, with a stoic Mamie gazing at her murdered child’s ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism. For almost a century, African Americans were lynched with regularity and impunity. Now, thanks to a mother’s determination to expose the barbarousness of the crime, the public could no longer pretend to ignore what they couldn’t see. (Watch the 100 Photos Documentary Short The Body of Emmett Till) (Note: Some images may be disturbing)

About the 100 Photos project: We began this project with what seemed like a straightforward idea: assemble a list of the 100 most influential photographs ever taken. How do you narrow a pool that large? You start by calling in the experts. We reached out to curators, historians and photo editors around the world for suggestions. Their thoughtful nominations whittled the field, and then we asked TIME reporters and editors to see if those held up to scrutiny. That meant conducting thousands of interviews with the photographers, picture subjects, their friends and family members and others, anywhere the rabbit holes led. It was an exhaustive process that unearthed some incredible stories that we are proud to tell for the first time, in both written stories and original documentary videos.

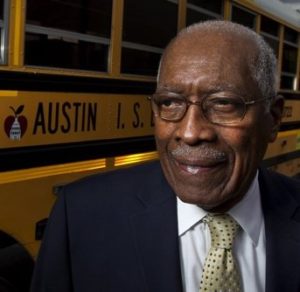

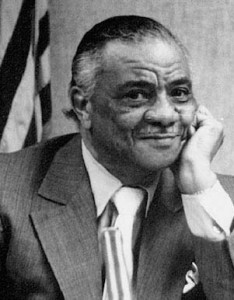

Obituary: Educator Charles Akins, pioneer in Austin school integration, 1932-2017

Longtime educator Charles Akins – a pioneer in the Austin school district’s integration efforts and for whom Akins High School in South Austin was named — died Wednesday, Mar. 29.

Longtime educator Charles Akins – a pioneer in the Austin school district’s integration efforts and for whom Akins High School in South Austin was named — died Wednesday, Mar. 29.

Akins, 84, was the first black teacher in an integrated high school in the Austin district, and was the district’s first black principal. He worked in the district for 41 years, then volunteered for more than a decade after that.

In 1964, when the district began to integrate its faculty, Akins became the first black teacher at Johnston High School, now Eastside Memorial. He was the first dean of boys at Johnston, then an assistant principal at Old Anderson and Lanier high schools. He later became an associate superintendent.

Trustee Paul Saldaña, who represents the part of the district that includes Akins High School, said Akins was “a true legend and trailblazer.”

“Dr. Akins was one of my local heroes who exemplified tremendous grace, integrity and leadership,” Saldaña said. “Our students, families, and teachers are eternally grateful to Dr. Akins for his life-long work, advocacy and commitment to public education and our AISD schools. Dr. Akins inspired our Akins’ students every day, reminding them the importance of education and personal responsibility.” (read more; also, The History Makers oral history interview)

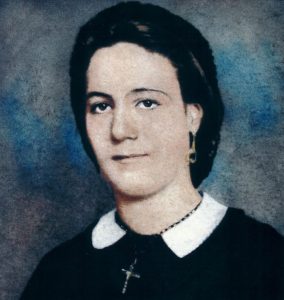

New Orleans Woman Could Become First African-American Saint

(Associated Press) Seven years after Pope Benedict declared a New Orleans free woman of color “venerable,” the Vatican is still studying whether two cures attributed to her are miracles.

It was 2011, and Archbishop Gregory Aymond was seeking a sacred antidote to the violence, murder and racism infesting his hometown. He turned to a venerable figure in New Orleans history, but one only vaguely known to even the most ardent Roman Catholics, and composed a prayer that is now recited at every local Mass. It ends with the plea: “Mother Henriette Delille, pray for us that we may be a holy family.”

She was a French-speaking woman of African descent, who was born in 1812 and lived a part of her life as a mistress in a social system known as placage, whereby wealthy white European men supported free women of color.

After her two young children died, Delille, then 24, experienced a religious transformation that led to the formation of the Sisters of the Holy Family order. The community of Creole nuns cared for those on the bottom rung of antebellum society, administering to the elderly, nursing the sick and teaching people of color, who at the time had limited education opportunities. To this day, Holy Family nuns continue good works around the globe.

Now, 175 years after she founded the order, Delille stands at the doorstep of sainthood. If canonized, she will become the first New Orleanian, and the first U.S.-born black person, recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. (read more)

Literary: The Lost Eleven, The Forgotten Story of Black American Soldiers Brutally Massacred in World War II

More than seven decades ago, on December 17, 1944, eleven black American GIs, were butchered in an isolated cow pasture in Wereth, Belgium, by a four-man German patrol of the 1st SS Division. Two months later, on February 15, a twelve-year-old Belgian boy, Hermann Langer, discovered the frozen bodies rotting in the melting snow. When U.S. officials examined the remains, they found multiple stab wounds, gouged eyes, shattered skulls, broken bones, and severed fingers, injuries meant to torture the men before the final kill. The dead men’s pockets contained small bibles, letters and photographs from loved ones, a silver cross, and a broken diamond engagement ring.

More than seven decades ago, on December 17, 1944, eleven black American GIs, were butchered in an isolated cow pasture in Wereth, Belgium, by a four-man German patrol of the 1st SS Division. Two months later, on February 15, a twelve-year-old Belgian boy, Hermann Langer, discovered the frozen bodies rotting in the melting snow. When U.S. officials examined the remains, they found multiple stab wounds, gouged eyes, shattered skulls, broken bones, and severed fingers, injuries meant to torture the men before the final kill. The dead men’s pockets contained small bibles, letters and photographs from loved ones, a silver cross, and a broken diamond engagement ring.

After a four-day investigation, Col. Burton Ellis closed the files, marking them “secret,” and burying them in the National Archives, where they gathered dust for 70 years. No one was ever brought to justice for the crimes. Their tragedy was omitted from the final congressional war Crimes Report of 1949, which recorded the names of all massacred victims—both civilian and military—and where each crime took place.

Now, for the first time in 70 years, the forgotten and tragic story of these eleven GIs is told in The Lost Eleven: The Forgotten Story of Black American Soldiers Brutally Massacred in World War II (Penguin Random House).

The lost eleven, soldiers of the segregated 333rd Field Artillery Battalion, were among the first African Americans trained for combat in WWII rather than placed in service positions. The men came from Southern states—Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, West Virginia, Arkansas, Georgia, South Carolina—where strict Jim Crow laws were enforced by law and with brutality. The men entered a segregated US Armed Forces, where they slept in separate barracks, ate in separate mess halls, and endured dehumanizing discrimination from white GIs. (read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Black Victory, The Rise and Fall of the White Primary in Texas,” by Darlene Clark Hine.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Black Victory, The Rise and Fall of the White Primary in Texas,” by Darlene Clark Hine.

In Black Victory, Darlene Clark Hine examines a pivotal breakthrough in the struggle for black liberation through the voting process. She details the steps and players in the 1944 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Smith v. Allwright, a precursor to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. She discusses the role that NAACP attorneys such as Thurgood Marshall played in helping black Texans regain the right denied them by white Texans in the Democratic Party: the right to vote and to have that vote count. Hine illuminates the mobilization of black Texans. She effectively demonstrates how each part of the African American community—from professionals to laborers—was essential to this struggle and the victory against disfranchisement.

This Week In Texas Black History, Apr. 2-8

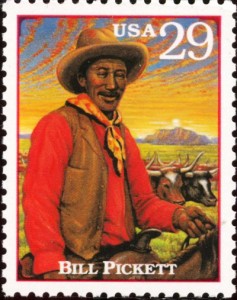

2 – On this date in 1932, Bill Pickett, the cowboy who invented the technique of “bulldogging” steers, passed away after being kicked in the head by a horse. On his radio show, Pickett’s friend Will Rogers announced the funeral at the 101 Ranch, near Ponca City, Okla., commenting: “Bill Pickett never had an enemy, even the steers wouldn’t hurt old Bill.” Known as the “Dusky Demon,” Pickett was a native of Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, he became the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

2 – On this date in 1932, Bill Pickett, the cowboy who invented the technique of “bulldogging” steers, passed away after being kicked in the head by a horse. On his radio show, Pickett’s friend Will Rogers announced the funeral at the 101 Ranch, near Ponca City, Okla., commenting: “Bill Pickett never had an enemy, even the steers wouldn’t hurt old Bill.” Known as the “Dusky Demon,” Pickett was a native of Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, he became the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

3 – In 1886, musician Arthur “Dooley” Wilson was born on this day in Tyler. Wilson is most notably known for his role as “Sam,” the piano player in the Humphrey Bogart film, “Cassablanca,” and the target of the famous line, “Play it again, Sam,” in reference to the song, “As Time Goes By.” Ironically, Wilson was actually a drummer and couldn’t play piano. In the film, he mimicked the hand movements of an off-screen pianist. Wilson also appeared on Broadway, including the play, “Cabin in the Sky.”

3 – In 1886, musician Arthur “Dooley” Wilson was born on this day in Tyler. Wilson is most notably known for his role as “Sam,” the piano player in the Humphrey Bogart film, “Cassablanca,” and the target of the famous line, “Play it again, Sam,” in reference to the song, “As Time Goes By.” Ironically, Wilson was actually a drummer and couldn’t play piano. In the film, he mimicked the hand movements of an off-screen pianist. Wilson also appeared on Broadway, including the play, “Cabin in the Sky.”

3 — In 1944, on this day, the U.S. Supreme Court rules in Smith v. Allwright that Texas’ “White primaries” could not exclude black voters. Civil Rights activist Dr. Lonnie Smith, a dentist, had attempted to vote in the 1940 Democratic Primary but was denied a ballot at his Houston precinct because voting was open only to whites. With help from the NAACP, Smith filed a suit that reached the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled in his favor, opening primary voting to all eligible Texans.

3 — In 1944, on this day, the U.S. Supreme Court rules in Smith v. Allwright that Texas’ “White primaries” could not exclude black voters. Civil Rights activist Dr. Lonnie Smith, a dentist, had attempted to vote in the 1940 Democratic Primary but was denied a ballot at his Houston precinct because voting was open only to whites. With help from the NAACP, Smith filed a suit that reached the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled in his favor, opening primary voting to all eligible Texans.

4 – On this day in 1974, Oscar DuConge (pronounced “dew-con-jay”) was elected Waco’s first African American mayor. Born in Pass Christian, Miss., the ninth of 14 children, DuConge grew up in New Orleans and graduated from Xavier University in 1931 with a degree in sociology. He moved to Waco in September 1948 following World War II and serving in the Army. He rose to political prominence when he was elected to the Waco City Council in 1972.

4 – On this day in 1974, Oscar DuConge (pronounced “dew-con-jay”) was elected Waco’s first African American mayor. Born in Pass Christian, Miss., the ninth of 14 children, DuConge grew up in New Orleans and graduated from Xavier University in 1931 with a degree in sociology. He moved to Waco in September 1948 following World War II and serving in the Army. He rose to political prominence when he was elected to the Waco City Council in 1972.

4 – Paul Quinn College was founded by a small group of African Methodist Episcopal preachers in Austin on this day in 1872. The school was relocated to Waco in 1877 and then to Dallas in 1990. The school is the oldest liberal arts college for African Americans in Texas and was named after William Paul Quinn who was A.M.E. Bishop of the Western States.

5 — Six weeks before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Archbishop Robert Lucey announced on this day in 1954 that all of San Antonio’s parochial schools and the city’s two Catholic colleges would be integrated.

5 — Six weeks before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Archbishop Robert Lucey announced on this day in 1954 that all of San Antonio’s parochial schools and the city’s two Catholic colleges would be integrated.

6 — Jazz pianist and black activist Horace Tapscott was born this day in Houston in 1934. By age six he had become a competent pianist. His family moved to Los Angeles in 1943 and Tapscott began his career and would play with Lionel Hampton though primarily as a trombonist, and would be a member of Motown Records’ West Coast band, backing such groups as the Supremes. Tapscott founded the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, also known as the Ark, a collective group dedicated to preserving and developing African-American musical traditions and promoting cultural and musical education. It also distributed free food to families in Watts and made available meeting space for black radicals such as Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Tapscott released fourteen albums.

6 — Jazz pianist and black activist Horace Tapscott was born this day in Houston in 1934. By age six he had become a competent pianist. His family moved to Los Angeles in 1943 and Tapscott began his career and would play with Lionel Hampton though primarily as a trombonist, and would be a member of Motown Records’ West Coast band, backing such groups as the Supremes. Tapscott founded the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, also known as the Ark, a collective group dedicated to preserving and developing African-American musical traditions and promoting cultural and musical education. It also distributed free food to families in Watts and made available meeting space for black radicals such as Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Tapscott released fourteen albums.

7 – On this day in 1954, All-Pro running back Tony Dorsett was born in Rochester, Pa. At the University of Pittsburgh, Dorsett won the 1976 Heisman Trophy and was a first round pick (No. 2 overall) by the Dallas Cowboys in the 1977 NFL Draft. He was Offensive Rookie of the Year and in 1994 was inducted to both the Pro Football and College Football halls of fame. That same year, he was also enshrined in the Texas Stadium Ring of Honor. Dorsett rushed for 12,739 yards (8th all-time) and 77 touchdowns in his 12-year career. His 99-yard touchdown run on January 3, 1983 against the Minnesota Vikings is the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history. See the run here.

7 – On this day in 1954, All-Pro running back Tony Dorsett was born in Rochester, Pa. At the University of Pittsburgh, Dorsett won the 1976 Heisman Trophy and was a first round pick (No. 2 overall) by the Dallas Cowboys in the 1977 NFL Draft. He was Offensive Rookie of the Year and in 1994 was inducted to both the Pro Football and College Football halls of fame. That same year, he was also enshrined in the Texas Stadium Ring of Honor. Dorsett rushed for 12,739 yards (8th all-time) and 77 touchdowns in his 12-year career. His 99-yard touchdown run on January 3, 1983 against the Minnesota Vikings is the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history. See the run here.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Holidays,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.