The Two Lives of Eugene Bullard

How the first black combat pilot escaped America, became a hero in France, and ended up an elevator operator in New York.

(PBS) In his own words, Eugene Bullard was the “first known Negro military pilot.” That, at least, was what was printed on his business cards. By that time, after a quarter-century in France, Bullard was back in the U.S., living in New York City, where he worked variously as a security guard, a perfume vendor, and a Rockefeller Center elevator operator. First known Negro military pilot; Bullard was a man both proud and humble, and his business card reflected that. But it also reflected the world in which he lived. His was not a first that had been formally recognized — much less celebrated. The story of how Eugene Bullard became the first black combat pilot, and why his achievement stayed in the shadows for so long, is a tale of alternate realities, of what happens when opportunity is offered or denied — and, ultimately, seized regardless.

Born in Columbus, Georgia in 1895, Bullard would recall that as a child, he was “as trusting as a chickadee and as friendly.” For a while, his parents were able to insulate him from the realities of racism so that he “loved everybody and thought everybody loved me.” But they could only do so much. When Bullard’s father got into a fight with a racist supervisor, a lynch mob came to the house. Bullard’s father survived, but was forced to go into hiding. Dreaming of a place “where white people treated colored people like human beings,” Bullard decided to run away. Accounts vary, but he was likely only 11 when he left home.

For the next five years, Bullard roamed around Georgia, encountering kindness and cruelty from a wide cast of characters along the way. At one point, he joined a band of English gypsies who opened his eyes to the possibility of a better life for African Americans in Europe. Crossing the Atlantic would become Bullard’s new objective; in 1912, at the age of 16, he stowed away on a ship leaving Norfolk, Virginia for Germany. It dropped him off in Scotland, where people treated him “just like one of their own.” Within 24 hours, he was “born into a new world” and “began to love everyone” once again. (read more, watch video)

- Related: The Great War — Drawing on unpublished diaries, memoirs and letters, The Great War tells the rich and complex story of World War I through the voices of nurses, journalists, aviators and the American troops who came to be known as “doughboys.” The series explores the experiences of African-American and Latino soldiers, suffragists, Native American “code talkers” and others whose participation in the war to “make the world safe for democracy” has been largely forgotten. The Great War explores how a brilliant PR man bolstered support for the war in a country hesitant to put lives on the line for a foreign conflict; how President Woodrow Wilson steered the nation through years of neutrality, only to reluctantly lead America into the bloodiest conflict the world had ever seen, thereby transforming the United States into a dominant player on the international stage; and how the ardent patriotism and determination to support America’s crusade for liberty abroad led to one of the most oppressive crackdowns on civil liberties at home in U.S. history. It is a story of heroism and sacrifice that would ultimately claim 15 million lives and profoundly change the world forever.

Commentary: Know the truth of Dallas’ hidden history, and be set free to heal

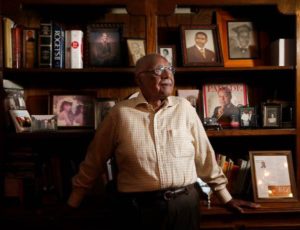

Dr. Claude Williams poses for a photograph at his home in Dallas, Wednesday, April 5, 2017. (Jae S. Lee/The Dallas Morning News) Staff Photographer

(Dallas News) Dr. Claude Williams did not have the luxury of simply being a top-notch dentist.

From the U.S. Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Md., where Williams integrated the Navy Dental Corps, to studying at Howard University, one of the most prestigious black institutions of higher learning in the world, Williams was a disciplined, straight-A student, eager to map out his next career move.

As a newly trained dentist, Williams could have chosen to go anywhere in America and establish a practice. But his heart was still back home in Texas, where he dreamed of having an impact on general dentistry and on the people he loved most.

By 1965, Williams and his wife, Helen, had three children and a new ranch home they had designed in Marshall, not far from Jefferson, where he grew up. The doctor’s thriving practice was soon legendary as word spread that black folks had someone who would not only take care of their dental hygiene, but do it with intelligence, professionalism, respect and integrity.

Life was good.

But Texas was going to need more from Claude Williams. This is the story of how one popular dentist moved to Dallas and quietly became a pioneer, changing health care for a large slice of the population. (read more)

Related: Dallas’ hidden history, celebrating the historic places that launched Dallas’ minority communities’ identities

60 Years Ago, Resistance To Integration In Texas Led To School Voucher Plan

(KUT Austin NPR) The Texas Senate Education Committee (discussed) a bill that would allow parents to use taxpayer dollars to send their kids to private schools. The school voucher program is cited as a way to give students — especially low-income students — access to high-quality schools.

This isn’t the first time lawmakers have tried to pass a school voucher bill; lawmakers have introduced some kind of modern-day voucher program for at least 20 years.

But vouchers have a history in Texas that dates back to school integration. And it’s not pretty.

After the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Texas was resistant to desegregating its public schools. Then-Gov. Allan Shivers appointed a committee to recommend ways to prevent integration. One proposal created a school voucher program that would give parents who opposed integration taxpayer money to send their children to a segregated private school. (read more, listen to interview)

Update: Dan Patrick gets House vote on school vouchers but opposite result he wanted

Obituary: Patricia McKissack, children’s author who brought black history to life, 1944-2017

(Washington Post) Patricia C. McKissack, a children’s author who chronicled African American history and Southern folklore in more than 100 early-reader and picture books, including award-winning works about chicken-coop monsters and a girl’s attempt to catch the wind, died April 7 at a hospital in Bridgeton, Mo. She was 72.

The cause was cardiac arrest, said a son, Fredrick McKissack Jr.

Mrs. McKissack was diagnosed several years ago with myotonic dystrophy, a muscle disorder, her son said, and was “really weakened” by the death in 2013 of her husband and frequent collaborator, Fredrick L. McKissack. She lived in the St. Louis suburb of Chesterfield.

With Fredrick McKissack handling the historical research and Mrs. McKissack focused on the writing, the couple crafted nonfiction works that sought to expose elementary- and middle-school readers to varied aspects of African American history.

Their books included “The Civil Rights Movement in America” (1987) and “A Long Hard Journey” (1989), about the organizing efforts of black Pullman railroad porters, as well as short biographies of black luminaries such as historian Carter Woodson (1991) and educator Mary McLeod Bethune (1985). (read more)

Briefs

- April 11, 1968: President Lyndon Johnson signed a civil rights act that came to be known as the Fair Housing Act. The act outlawed discrimination in the sale, rental or leasing of 80 percent of U.S. housing. It also protected civil rights workers and made it a federal crime to cross state lines with the intention of starting a riot.

- April 12, 1861: The American Civil War began, lasting four years. More than 600,000 died in battle — almost as many as died in all other U.S. conflicts combined. During the war, tens of thousands of African Americans fled slavery, escaping to Union lines for freedom. By the end of the war, more than 180,000 African Americans, mostly from the South, went on to fight with the Union forces, and slavery as an institution no longer existed.

- April 12, 1864: The Battle of Fort Pillow took place at Fort Pillow, 40 miles north of Memphis, Tennessee. According to Union sources, after the Union troops surrendered, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men massacred the mostly African-American troops in cold blood. Confederate sources insisted, however, that the troops never surrendered.

- April 13, 1873: On Easter Sunday, the White League, a paramilitary group intent on securing white rule in Louisiana, clashed with Louisiana’s almost all-black state militia. The death toll was staggering: only three members of the White League died, but some 100 African-American men were killed. Of those, nearly half were killed in cold blood after they surrendered. What happened became known as the Colfax Massacre.

- April 14, 1853: Harriet Tubman made her first of 19 trips back to the South to ensure that hundreds of others that were enslaved also made their way to freedom. She was never caught, despite a $40,000 reward for her capture. In an interview, she recalled her own freedom, saying, “I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now I was free. There was such glory over everything … I felt like I was in heaven.”

- April 15, 1947: Jackie Robinson broke through the color barrier in Major League Baseball, becoming the first African-American player in the 20th century. He was active in the civil rights movement and became the first African-American television analyst in Major League Baseball and the first African-American vice-president of a major American corporation. In recognition of his achievements, Robinson was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Major League Baseball has retired his number “42,” which became the title of the movie about his breakthrough. Robinson did more than just break the color barrier — he became a leader for equal rights for all Americans.

TIPHC Bookshelf

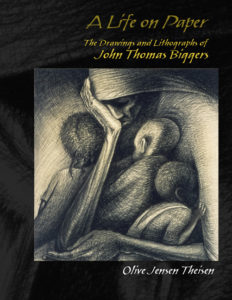

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “A Life on Paper, The Drawings and Lithographs of John Thomas Biggers,” by Olive Jensen Theisen.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “A Life on Paper, The Drawings and Lithographs of John Thomas Biggers,” by Olive Jensen Theisen.

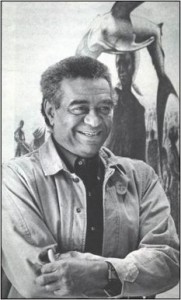

John Thomas Biggers (1924–2001) was a major African American artist who inspired countless others through his teaching, murals, paintings, and drawings. After receiving conventional art training at Hampton Institute and Pennsylvania State, he had his personal and artistic breakthrough in 1957 when he spent six months in the newly independent country of Ghana. From this time forward, he integrated African abstract elements with his rural Southern images to create a personal iconography. His new approach made him famous, as his personal discovery of African heritage fit in well with the growing U.S. civil rights movement. He is best known for his murals at Hampton University, Winston-Salem University, and Texas Southern, but the drawings and lithographs that lie behind the murals have received scant attention—until now.

Theisen interviewed Dr. Biggers during the last thirteen years of his life, and was welcomed into his studio innumerable times. Together, they selected representative works for this volume, some of which have not been previously published for a general audience. After his death in 2001, his widow continued to work closely with Theisen, resulting in a book that is intimate and informative for both the scholar and the student.

This Week in Texas Black History, Apr. 9-15, 2017

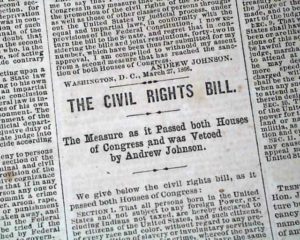

9 – On this day, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 became effective, granting citizenship and the same rights enjoyed by white citizens to all male persons in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” President Andrew Johnson‘s veto of the bill was overturned by a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, and the bill became law.

9 – On this day, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 became effective, granting citizenship and the same rights enjoyed by white citizens to all male persons in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” President Andrew Johnson‘s veto of the bill was overturned by a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, and the bill became law.

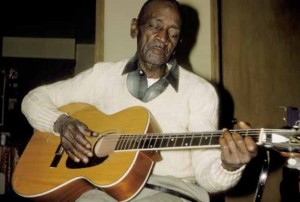

9 – On this day in 1895, blues singer and guitarist Bowdie Glenn Lipscomb was born in Navasota. As a youngster, Lipscomb would take the name “Mance,” short for “Emancipation,” the name of an elder family friend. Lipscomb, who preferred to be known as a “songster” because of the variety of songs he sang, was discovered and first recorded in 1960 during the country blues revival. The annual Navasota Blues Festival is held in his honor. A bronze sculpture of him was unveiled in Mance Lipscomb Park in Navasota on 2011.

9 – On this day in 1895, blues singer and guitarist Bowdie Glenn Lipscomb was born in Navasota. As a youngster, Lipscomb would take the name “Mance,” short for “Emancipation,” the name of an elder family friend. Lipscomb, who preferred to be known as a “songster” because of the variety of songs he sang, was discovered and first recorded in 1960 during the country blues revival. The annual Navasota Blues Festival is held in his honor. A bronze sculpture of him was unveiled in Mance Lipscomb Park in Navasota on 2011.

10 – Golfer Lee Elder, a Dallas native, became the first African-American to play in the Masters Tournament on this day in 1975. Leading to the tournament, Elder endured hate mail that said he would never make it to Augusta and that he should “watch your step when you get to Augusta,” and that “there will be blood.” Undaunted, Elder competed in the tournament, but missed the cut after shooting 152 (8-over par) for the first two rounds.

10 – Golfer Lee Elder, a Dallas native, became the first African-American to play in the Masters Tournament on this day in 1975. Leading to the tournament, Elder endured hate mail that said he would never make it to Augusta and that he should “watch your step when you get to Augusta,” and that “there will be blood.” Undaunted, Elder competed in the tournament, but missed the cut after shooting 152 (8-over par) for the first two rounds.

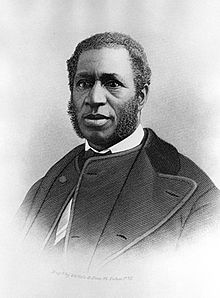

12 – Richard Harvey Cain was born on this day in 1825 in Virginia to free parents. Cain was a political and civic leader of the Charleston, South Carolina reconstruction era. In 1848, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was a minister in Muscatine, Iowa. He became a bishop of the church in 1880 and was assigned to the Louisiana and Texas district. That same year, he helped found Paul Quinn College in Austin, serving as the school’s president until 1884.

12 – Richard Harvey Cain was born on this day in 1825 in Virginia to free parents. Cain was a political and civic leader of the Charleston, South Carolina reconstruction era. In 1848, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was a minister in Muscatine, Iowa. He became a bishop of the church in 1880 and was assigned to the Louisiana and Texas district. That same year, he helped found Paul Quinn College in Austin, serving as the school’s president until 1884.

13 — On this date in 1924, internationally acclaimed artist, sculptor, teacher and philosopher John Biggers was born in Gastonia, North Carolina. After studying at Hampston Institute and Penn State University, Biggers moved to Houston in 1949 and became founding chairman of the art department at Texas Southern University, then called Texas State University for Negroes. He held the position for 34 years during which he initiated a mural program for art majors in which every senior student was expected to complete a mural on campus: there are now 114 such murals on the Texas Southern campus. In 1957, with the help of a grant from UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), Biggers was one of the first American black artists to visit Africa to study African traditions and culture.

13 — On this date in 1924, internationally acclaimed artist, sculptor, teacher and philosopher John Biggers was born in Gastonia, North Carolina. After studying at Hampston Institute and Penn State University, Biggers moved to Houston in 1949 and became founding chairman of the art department at Texas Southern University, then called Texas State University for Negroes. He held the position for 34 years during which he initiated a mural program for art majors in which every senior student was expected to complete a mural on campus: there are now 114 such murals on the Texas Southern campus. In 1957, with the help of a grant from UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), Biggers was one of the first American black artists to visit Africa to study African traditions and culture.

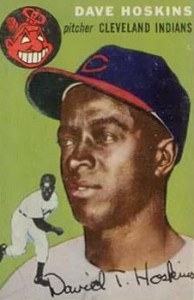

13 – On this day in 1952 David Hoskins started for the Dallas Eagles making him the first black player in the Class AA Texas League. The Eagles were affiliated with the Cleveland Indians. Hoskins was born in Greenwood, Mississippi, on August 3, 1925 but moved to Flint, Mich. with his family in 1936. He played for the Homestead Grays in the Negro American League and in 1948 broke a color barrier as an outfielder with Grand Rapids of the Central League. With the Eagles, Hoskins was an immediate draw and by the season’s end had pitched before sellout crowds at every stadium in the league and led the league in wins (22), complete games (26), innings pitched (280), and had an ERA of 2.12. He also hit .328 and was an all-star selection. He was inducted into the Texas League Hall of Fame in 2004. In 1953, Hoskins was signed by the Indians and played for two seasons, 1953-54. For his Major League career, Hoskins was 9-4 with a 3.81 ERA and .227 batting average.

13 – On this day in 1952 David Hoskins started for the Dallas Eagles making him the first black player in the Class AA Texas League. The Eagles were affiliated with the Cleveland Indians. Hoskins was born in Greenwood, Mississippi, on August 3, 1925 but moved to Flint, Mich. with his family in 1936. He played for the Homestead Grays in the Negro American League and in 1948 broke a color barrier as an outfielder with Grand Rapids of the Central League. With the Eagles, Hoskins was an immediate draw and by the season’s end had pitched before sellout crowds at every stadium in the league and led the league in wins (22), complete games (26), innings pitched (280), and had an ERA of 2.12. He also hit .328 and was an all-star selection. He was inducted into the Texas League Hall of Fame in 2004. In 1953, Hoskins was signed by the Indians and played for two seasons, 1953-54. For his Major League career, Hoskins was 9-4 with a 3.81 ERA and .227 batting average.

14 – On this day in 1935, Julius “Jay” Parker, Jr. was born in New Braunfels. Parker attended Prairie View A&M University where he completed the Reserve Officers Training Corps curriculum in 1955. Parker rose to the rank of major general and became the highest ranking African-American Military Intelligence Officer in the history of the U.S. Army. He is also a direct descendant of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanche nation.

14 – On this day in 1935, Julius “Jay” Parker, Jr. was born in New Braunfels. Parker attended Prairie View A&M University where he completed the Reserve Officers Training Corps curriculum in 1955. Parker rose to the rank of major general and became the highest ranking African-American Military Intelligence Officer in the history of the U.S. Army. He is also a direct descendant of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanche nation.

14 – Born in Houston on this day in 1938, Gloria Dean Randle Scott became the first African-American president of the Girl Scouts of America. A civic and educational leader, she took the post in 1975. Scott graduated from Jack Yates High School and received post graduate degrees, including education, from Indiana University. She had been a Junior Girl Scout at and later served as President of the Negro Girl Scout Senior Planning Board. In 1987, she was selected as president of Bennett College, in Greensboro, North Carolina. In 2001, she returned to Texas and was very active in the Corpus Christi community, including the Black Chamber of Commerce.

14 – Born in Houston on this day in 1938, Gloria Dean Randle Scott became the first African-American president of the Girl Scouts of America. A civic and educational leader, she took the post in 1975. Scott graduated from Jack Yates High School and received post graduate degrees, including education, from Indiana University. She had been a Junior Girl Scout at and later served as President of the Negro Girl Scout Senior Planning Board. In 1987, she was selected as president of Bennett College, in Greensboro, North Carolina. In 2001, she returned to Texas and was very active in the Corpus Christi community, including the Black Chamber of Commerce.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Holidays,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.