Long-lost manuscript contains searing eyewitness account of 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Following World War I, Tulsa boasted one of the most affluent African American communities in the country, known as the Greenwood District. This thriving business district and surrounding residential area was referred to as “Black Wall Street.” All of that changed after a series of events resulted in the Tulsa race riots in which 35 city blocks lay in charred ruins, over 800 people were treated for injuries and contemporary reports of deaths began at 36. In 2001, the Tulsa Race Riot Commission released a report indicating that historians now believe close to 300 people died in the riot.

In the early morning hours of June 1, 1921, Black Tulsa was looted and burned by white rioters. Martial law was declared and National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa. Guardsmen assisted firemen in putting out fires, took imprisoned blacks out of the hands of vigilantes and imprisoned all black Tulsans not already interned. Over 6,000 people were held at the Convention Hall and the Fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days.

Now, a harrowing 10-page manuscript resides among the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The previously unknown document was found last year, purchased from a private seller by a group of Tulsans and donated to the museum with the support of the Buck Colbert Franklin family. B.C. Colbert was a lawyer and father of famed historian John Hope Franklin.

The elder Franklin’s manuscript is typewritten, on yellowed legal paper, and folded in thirds. But the words, an eyewitness account of the May 31, 1921, racial massacre are a searing description of the attack by hundreds of whites on the thriving black neighborhood in the booming oil town. “Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top.”

Read about Franklin and his manuscript and the Tulsa riots here. (Video included.)

Featured image above: Practicing law in a Red Cross tent are B.C. Franklin (right) and his partner I.H. Spears with their secretary Effie Thompson on June 6, 1921, five days after the massacre. (NMAAHC, Gift from Tulsa Friends and John W. and Karen R. Franklin)

Gentrification: The End of Black Harlem

Invisible Man: A Memorial to Ralph Ellison by Sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, 2003. Riverside Park at 150th Street, in Harlem. Credit, Joseph Michael Lopez for The New York Times

Michael Henry Adams conducts tours in Harlem and is the author of “Harlem: Lost and Found, an Architectural and Social History, 1765-1915.” He writes, in a story for the New York Times: “Harlem has seen an influx of tourists, developers and stroller-pushing young families, described in the media as “urban pioneers,” attracted by city tax abatements. New high-end housing and hip restaurants have also played their part. So have various public improvements, like new landscaping and yoga studios. In general, all this activity has helped spruce the place up….Rents are rising; historic buildings are coming down. The Renaissance, where Duke Ellington performed, and the Childs Memorial Temple Church of God in Christ, where Malcolm X’s funeral was held, have all been demolished. Night life fixtures like Smalls’ Paradise and Lenox Lounge are gone….But this is the problem with gentrification.

“To us, our Harlem is being remade, upgraded and transformed, just for them, for wealthier white people…There is something about black neighborhoods, or at least poor black neighborhoods, that seem to make them irresistible to gentrification.”

Read his story about how gentrification is changing the cultural and economic face of this iconic black neighborhood.

HBCUs: The mission of a black baseball team

According to a report published last year by USA Today, less than eight per cent of major-league players in 2015 were African-American; that figure was nineteen per cent in 1986. And the decline can be seen at every level of the game: Little League, the minors, high school, college—even HBCUs. Thirty years ago, it was virtually impossible to find a white player on an HBCU team. Today, Winston-Salem State, Florida A&M, Prairie View A&M, and North Carolina Central all field teams in which the majority of players are not black. Only a few schools—Clark Atlanta, Morehouse College, and Lane College—regularly fill their rosters entirely with black players.

Kentaus Carter, head coach at Clark Atlanta, meanwhile, takes pride in fielding a team made up almost entirely of black players. According to Jason Howell, the Panthers’ promising first baseman, the team’s makeup helps amplify the benefits of going to a school like Clark Atlanta. “Attending an HBCU, you’re getting an experience that you can’t get at a PWI”—a predominantly white institution—“or other institution,” the soft-spoken freshman said. “It’s more than baseball when you’re at an HBCU, it’s about getting back to your roots, getting back to the people that have laid the foundation for us.”

Read here John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro’s piece for The New Yorker about Carter’s approach at Clark Atlanta and the challenges of fielding baseball teams at HBCUs.

HBCU graduates get ready to take on the world

From The Undefeated, here is a sampling of the advice and wisdom shared recently with HBCU grads from a who’s who of commencement speakers such as President Obama (at Howard University), the first lady, Oprah and others. (Several videos included.)

From The Undefeated, here is a sampling of the advice and wisdom shared recently with HBCU grads from a who’s who of commencement speakers such as President Obama (at Howard University), the first lady, Oprah and others. (Several videos included.)

Their most oft-repeated advice:

- Success doesn’t come without failure.

- You’re not in this alone.

- Embrace your racial identity.

- Embrace your technology.

- And always, have faith.

“Always think of those who came before,” Winfrey reminded the 300-plus graduates at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, N.C. She rattled off the names Sojourner Truth, Benjamin Banneker, Langston Hughes, “the roots of the branches.”

And she passed along advice from black leaders she remembered from her childhood.

“Excellence is the best deterrent for racism,” she remembered from Jesse Jackson. “So be excellent at whatever you do, even if it’s flipping fries.”

In brief

- June 2, 1971 – Samuel L. Gravely, Jr. becomes first African American admiral in U.S. Navy.

- June 1, 1968 – Henry Lewis becomes first Black musical director of an American symphony orchestra – the New Jersey Symphony

- May 30 1965 – Vivian Malone becomes the first African American to graduate from the University of Alabama.

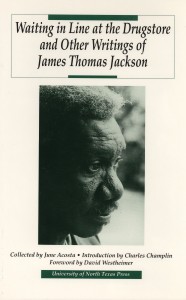

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Waiting in Line at the Drugstore and Other Writings of James Thomas Jackson,” by James Thomas Jackson.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Waiting in Line at the Drugstore and Other Writings of James Thomas Jackson,” by James Thomas Jackson.

A black man’s struggles from the Thirties through the Seventies provide the focus for this collection of essays, articles, fiction, and poetry. As a charter member of the Watts Writers Workshop, Jackson gained the attention and respect of Budd Schulberg for the stories of his childhood in Houston and his service in the army. A high school dropout, Jackson dedicated his life to writing, a habit that kept him in poverty; he worked at odd jobs until his death at age 59.

This Week In Texas Black History, May 29-June 4

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Good  win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “The “Roots” of the problem.” Read it

win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “The “Roots” of the problem.” Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.