African American men, women and children, who took part in The Great Migration in Chicago in 1918. Credit: Chicago History Museum, via Getty Images

Tales of African-American History Found in DNA

In a recent study, a team of geneticists sought evidence for the migration of Africans and African Americans — via the Transatlantic slave trade and the Great Migration — in the DNA of living African-Americans. The findings, published in PLOS Genetics, provide a map of African-American genetic diversity, shedding light on both their history and their health.

Buried in DNA, the researchers found the marks of slavery’s cruelties, including further evidence that white slave owners routinely fathered children with women held as slaves.

The importance of that finding is not just historical, said Dr. Esteban G. Burchard, a physician and scientist at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

A detailed map of genetic variations in African-Americans will help show how genes influence their risk for various diseases. “This has tremendous medical relevance,” he said.

Until recently, most research into the link between genes and disease has focused on people of European descent. “We’re missing out on a lot of biology and diversity,” said Simon Gravel, a geneticist at McGill University in Montreal.

Read more of this story from of the New York Times.

A Quick Guide to Researching African-American Roots

The publication of author Alex Haley’s 1976 Pulitzer Prize-winning family saga ROOTS and the subsequent 1977 ABC miniseries inspired millions to investigate their own family lineages. In the ensuing four decades, interest in genealogy has only grown, and advances in record digitization and DNA testing have opened new doors for tracing African-American family trees. As HISTORY introduces ROOTS to a new generation, explore the latest tools available for anyone researching their slave ancestors.

The publication of author Alex Haley’s 1976 Pulitzer Prize-winning family saga ROOTS and the subsequent 1977 ABC miniseries inspired millions to investigate their own family lineages. In the ensuing four decades, interest in genealogy has only grown, and advances in record digitization and DNA testing have opened new doors for tracing African-American family trees. As HISTORY introduces ROOTS to a new generation, explore the latest tools available for anyone researching their slave ancestors.

After Emanuel church shooting, push to tell more African-American history in public gains momentum in S.C.

The Denmark Vesey Monument in Hampton Park, installed in 2014, honors the man behind a planned slave rebellion in 1822 and a founder of Emanuel AME Church. Grace Beahm/Staff

But the call for a more balanced narrative recently has grown louder. The shootings at Emanuel AME Church that killed nine black worshippers last June raised a nationwide discussion about Confederate symbolism in the South and underscored the need to tell a fuller story.

The alleged shooter, Dylann Roof, posted photos of himself online posing at sites connected to the Confederacy and holding the Confederate battle flag. Weeks after the shootings, South Carolina legislators made the historic decision to remove the flag from the Statehouse grounds.

Since then, debate has escalated about whether Confederate monuments should be demoted or removed altogether from public spaces. Meanwhile, many say updating the landscape to include more African-American stories should be the immediate goal.

Redux Contemporary Art Center seemed to drive home that point with the colorful mural it installed on its St. Philip Street building this month to pay tribute to S.C. Sen. Clementa Pinckney, who was killed at Emanuel. It includes his portrait next to a quote he once said: “Across the South, we have a deep appreciation of history. We haven’t always had a deep appreciation of each other’s history.” (more)

Related: Click here to find African-American historical markers in Texas.

How history keeps African Americans out of state parks

Recent studies have shown that visitors to U.S. national and state parks are disproportionately white, with low numbers of ethnic minorities, especially African Americans.

Recent studies have shown that visitors to U.S. national and state parks are disproportionately white, with low numbers of ethnic minorities, especially African Americans.

A new study identifies several reasons why African Americans choose not to patronize public parks in greater numbers, including a racist history that curtailed African Americans’ access to parks, on-going racial conflict within communities near parks, and a lack of African-American heritage at parks.

“The benefits of national and state parks for American society are numerous, including great observed health benefits,” says lead researcher KangJae “Jerry” Lee. “Because these parks are such a valuable resource, it is concerning that many racial and ethnic minorities are not taking advantage of the public spaces, which they help fund through tax dollars.” (more)

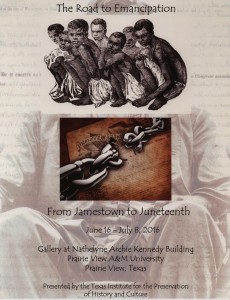

New TIPHC Exhibit, “The Road to Emancipation – From Jamestown to Juneteenth”

The Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture will open its Juneteenth exhibit on Thursday, June 16 at 1 p.m. in the School of Architecture Gallery. Entitled, “From Jamestown to Juneteenth,” the display will trace the path of black slaves, who first arrived in the U.S. at Jamestown in 1619 as part of the Transatlantic slave trade, to their freedom in 1863 with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The path of slavery ended in 1865 when Texas slaves were finally given word of their freedom on June 19. The exhibit covers how the proclamation came to be, its effect on the Civil War, slavery in Texas, how the news of emancipation was received in the Lone Star State and why it took two and a half years to get here.

The Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture will open its Juneteenth exhibit on Thursday, June 16 at 1 p.m. in the School of Architecture Gallery. Entitled, “From Jamestown to Juneteenth,” the display will trace the path of black slaves, who first arrived in the U.S. at Jamestown in 1619 as part of the Transatlantic slave trade, to their freedom in 1863 with President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. The path of slavery ended in 1865 when Texas slaves were finally given word of their freedom on June 19. The exhibit covers how the proclamation came to be, its effect on the Civil War, slavery in Texas, how the news of emancipation was received in the Lone Star State and why it took two and a half years to get here.

The exhibit is open to the public and will be on display through July 8. For more information, contact Michael Hurd, TIPHC director, at 936-261-9836, or mdhurd@pvamu.edu.

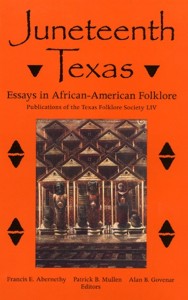

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African-American Folklore,” editors Francis Edward Abernethy, Alan B. Govenar, and Patrick B. Mullen.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African-American Folklore,” editors Francis Edward Abernethy, Alan B. Govenar, and Patrick B. Mullen.

An exploration of African-American folkways and traditions from both African-American and white perspectives. Included are descriptions and classifications of different aspects of African-American folk culture in Texas; explorations of songs and stories and specific performers such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Manse Lipscomb, and Bongo Joe; and a section giving resources for the further study of African-Americans in Texas.

This Week In Texas Black History, June 5-11

5 – On this day in 1950, The U.S. Supreme Court ordered Heman Sweatt admitted to the University of Texas Law School. In handing down its decision in Sweatt v. Painter, the Court concluded that black law students were not offered substantial quality in educational opportunities and that Sweatt could therefore not receive an equal education in a separate law school. Sweatt had teamed with the NAACP to challenge the admissions policy at the UT Law School. The NAACP was looking to test separate but equal education statutes in Texas and the result of Sweatt’s legal battle struck down segregationist policies at the school (for graduate and professional programs only), gained him admission, and paved the way for the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which opened integration for undergraduates.

5 – On this day in 1950, The U.S. Supreme Court ordered Heman Sweatt admitted to the University of Texas Law School. In handing down its decision in Sweatt v. Painter, the Court concluded that black law students were not offered substantial quality in educational opportunities and that Sweatt could therefore not receive an equal education in a separate law school. Sweatt had teamed with the NAACP to challenge the admissions policy at the UT Law School. The NAACP was looking to test separate but equal education statutes in Texas and the result of Sweatt’s legal battle struck down segregationist policies at the school (for graduate and professional programs only), gained him admission, and paved the way for the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which opened integration for undergraduates.

6 – On this day in 1944, Olympic sprint champion Tommie Smith was born in Clarksville. The seventh of 12 children, he survived a life-threatening bout of pneumonia as an infant. Smith is the only man in the history of track and field to hold 11 world records simultaneously. At San Jose State University, he tied or broke 13 world records. However, he is most remembered as one half of the duo of black U.S. Olympians – along with John Carlos – who, during the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, stood on the victory stand with heads bowed and raised clinched fists in a demonstration for human rights, liberation and solidarity. The protest overshadowed Smith’s performance on the track where he broke the world and Olympic records, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter sprint with a time of 19.83 seconds. The story of the “silent gesture” is captured in the 1999 HBO-TV documentary, “Fists of Freedom.” In 1978, Smith was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and has accumulated many other honors.

6 – On this day in 1944, Olympic sprint champion Tommie Smith was born in Clarksville. The seventh of 12 children, he survived a life-threatening bout of pneumonia as an infant. Smith is the only man in the history of track and field to hold 11 world records simultaneously. At San Jose State University, he tied or broke 13 world records. However, he is most remembered as one half of the duo of black U.S. Olympians – along with John Carlos – who, during the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, stood on the victory stand with heads bowed and raised clinched fists in a demonstration for human rights, liberation and solidarity. The protest overshadowed Smith’s performance on the track where he broke the world and Olympic records, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter sprint with a time of 19.83 seconds. The story of the “silent gesture” is captured in the 1999 HBO-TV documentary, “Fists of Freedom.” In 1978, Smith was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and has accumulated many other honors.

7 – On this day in 1950, John Chase enrolled in the University of Texas School of Architecture graduate program, becoming the first African-American to enroll at a major university in the South. Chase, a native of Annapolis, Md., earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first black graduate of the University. That same year, he also became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade. In 1980, he became the first African-American appointed to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts. His firm’s designs include: the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, the Harris County Astrodome Renovation, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University.

7 – On this day in 1950, John Chase enrolled in the University of Texas School of Architecture graduate program, becoming the first African-American to enroll at a major university in the South. Chase, a native of Annapolis, Md., earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first black graduate of the University. That same year, he also became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade. In 1980, he became the first African-American appointed to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts. His firm’s designs include: the George R. Brown Convention Center in Houston, the Harris County Astrodome Renovation, and the Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern University.

9 – On this date in 1965 the University Interscholastic League State Executive Committee validated the Legislative Council’s decision to open league membership to all public schools. The UIL was formed in 1913 with the stipulation that its membership was open only to white schools. In 1920, the Prairie View Interscholastic League was formed as the UIL’s counterpart to govern academic and athletic competitions for the state’s high schools for black students. Black schools began UIL competition in the 1967-68 school year. After the 1969-70 school year, the UIL fully absorbed all PVIL member schools. The PVIL played a leading role in developing African-American students in the arts, literature, athletics and music from the 1920’s through 1970. Among its football stars, alone, were: Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Ernie Ladd (Orange Wallace), and Jerry Levias (Beaumont Hebert).

9 – On this date in 1965 the University Interscholastic League State Executive Committee validated the Legislative Council’s decision to open league membership to all public schools. The UIL was formed in 1913 with the stipulation that its membership was open only to white schools. In 1920, the Prairie View Interscholastic League was formed as the UIL’s counterpart to govern academic and athletic competitions for the state’s high schools for black students. Black schools began UIL competition in the 1967-68 school year. After the 1969-70 school year, the UIL fully absorbed all PVIL member schools. The PVIL played a leading role in developing African-American students in the arts, literature, athletics and music from the 1920’s through 1970. Among its football stars, alone, were: Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard), “Mean” Joe Greene (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Ernie Ladd (Orange Wallace), and Jerry Levias (Beaumont Hebert).

11 — On this day in 1991, Connie Yerwood died in Austin. In 1937, she became the first African American doctor to work for Texas Public Health Services. The Victoria native would also become the first black director of Maternal and Child Services in Texas and the first black chief of the Bureau of Personal Health Services. Yerwood was a long-time trustee of Samuel Huston College and the national president of its National Alumni Association.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Good  win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “The “Roots” of the problem.” Read it

win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “The “Roots” of the problem.” Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.