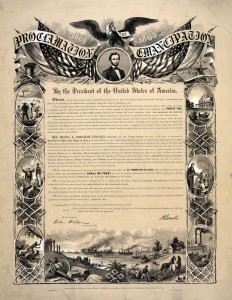

The months and years after the Emancipation Proclamation finally made it to Texas on June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth) were full of uncertainty and movement for ex-slaves. After having every part of their lives controlled by their owners, these African Americans had to figure out how they were going to put food on the table, house themselves, and make a better future for their families than the past they had endured. In many cases the end of slavery meant that African Americans could try to reunite their families by looking for sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and other loved ones who had been separated from them by sale to different owners in other states. While some traveled in the iconic wagon trains of Western history, most walked from place to place searching for new possibilities (Taylor).

The ex-slaves’ fates were not fully decided by emancipation which instead opened up a whole new series of questions about civil rights and enfranchisement that had never existed before. Would the men be able to vote? Would the families be able to own land? How would the southern cotton industry, so dependent on the labor of enslaved people, be restored from the devastation of war without that free labor? Would ex-slaves of all ages be able to go to school to learn reading, writing and arithmetic skills that had been denied to most of them in slavery? Who would be able to marry legally? Could white men face criminal charges for sexually exploiting black women as they had done in slavery? Would interracial marriage be prohibited?

Not only were all these issues unresolved, but some white people in this former Confederate state were determined that black ex-slaves would not be free or equal. They terrorized and undermined the ex-slaves however they could. Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Education and Abandoned Lands or the Freedmen’s Bureau (Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the State of Texas) are replete with reports of violence against blacks who had barely tasted freedom. Here are a few excerpts showing how random and gruesome the racial violence could be, and how seldom the perpetrators were punished for their crimes:

- In Grason [sic] County six miles from this place three freedmen by names were [sic] Monroe White, Jim Douglass and Jack Thomas were called up one night at a late hour by a man who wanted assistance to put a tire on his wagon. Two days afterward their bodies were found some distance from their house shot and cut all to pieces.

- In August, 1865 a freedman named King Davis was shot and killed on Mill Creek by one Davis known as ‘Dock Davis.’ This freedman it is alleged was murdered for attempting to leave Davis and fined [sic] employment elsewhere after learning that he was free. A military force by Capt. Post Comndg [sic] at Brenham (went) to arrest Davis but failed to find him. He has however returned and is now living on Mill Creek nine miles south of Brenham.

- On the 28th day of April 1866 at or near Union Hill in Washington County were murdered two freedmen and one freedwoman named respectively James Mayfield, Green Taylor and Maria Taylor. There [sic] murders were committed at night by a party of white men eight or ten in number. The freedmen, five in number, lived alone in a house upon a Mr. Husier’s farm. The two persons who were spared – an old man and woman – could not swear positively to the names of the murderers but thought they were young men of the neighborhood. Four arrests were made and two of the number tried by military Commission and acquitted for lack of positive evidence.

- In Bonham in Fannin County about the 2nd Sept. last during a show that was coming off a couple of desperate men concluded to thin the niggers out a little and drive them back to their holes as they said. Fired into a crowd of freedmen going to the show. Killed three and wounded quite a number. An effort was made to arrest the party but failed. These men are still in the county fearless of any consequence.

It was during the unsettled years after the Civil War that the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist terroristic organizations, which used lynching and white riots against black politicians and others, were formed to keep black people in their place. Jim Crow and Black Codes eventually enshrined in culture and laws a strict system of racial segregation and white supremacy that would plague blacks until the civil rights movement of the mid-twentieth century.

Despite harassment Texas’s African American population grew. The total African American population of Texas went from 182,921 before the war in 1860 to 253,475 in 1870 to 393,384 in 1880. In 1870, blacks were roughly 30 percent of Texas’s total population of about 820,000 (Taylor).

This growth in the state of African American population was driven by migration into the state and the birthrate among blacks, whose primary concern was their families. In Texas, slaves were prohibited from getting married, and no enslaved child was considered legitimate. Free black people were not permitted to live in the state. For a while after emancipation, at the urging of the Freedmen’s Bureau some slave marriages were treated the same as common law marriages. Finally in 1870, after the bureau had ceased its activities in anything other than education, the state Legislature legalized marriages of enslaved people and declared their children legitimate (Washington).

Most black people gravitated to cities, such as San Antonio, Houston or Austin to find work and settle (Barr; Taylor). It is important to remember that Texas was younger than the other confederate states that had to be reintegrated into the U.S.A. after they had seceded at the beginning of the Civil War. The bulk of Texas’s black population lived in East Texas where they had been brought by slave owners and were needed to work the land on cotton plantations. After emancipation, there was some migration into central and west Texas (Taylor).

Black neighborhoods sprang up in large and small cities in Texas, gaining the dignified or the pejorative names of the day such as Niggertown. In Houston, there was Freedmen’s Town or “Little Harlem,” (Sanders); Austin, the state capital, had Clarksville, site of early schools and small Victorian homes owned by black families. The Gold Dollar Newspaper Building, which was renovated into a restaurant, (Bliss) is all that remains of African American Wheatsville in Austin. The paper was published by Jacob Fontaine, a former slave, who founded several churches, businesses and grocery stores. Fontaine was one of the most influential African Americans in Texas (Thompson). Quakertown in Denton, which is about 40 miles north of Dallas, was located not far from what is now Texas Woman’s University. At its height, Quakertown had several successful black-owned businesses including a pharmacy and a seamstress, and many of its residents walked up a hill from their small Victorian homes to their jobs on campus. This black community, however, was forced to relocate to a mosquito-ridden part of town to make way for other developments in the 1920s.

Trying to live off the land

At the end of the Civil War, much of the state was considered open land, free for the settling. “Forty acres and a mule” had turned out to be a cruel rumor sparked by General Sherman’s policy in South Carolina of redistributing property from white plantation owners to enslaved men and women at the end of the war. Black and other political leaders pushed for nationalization of this policy throughout the confederate states, but it faced fierce opposition in Congress and never became part of federal law (History.com; McCurdy). The Freedmen’s Bureau, which was established by the U.S. government in 1865 to help the ex-slaves get land and other resources, was not the most effective agency. Seventy-seven percent of the applicants for land under the Southern Homestead Act, administered by the bureau, were white. All these applicants had to do to qualify for help from the Bureau was to swear that they had never taken up arms against the Union. (Oliver and Shapiro).

At the end of the Civil War, much of the state was considered open land, free for the settling. “Forty acres and a mule” had turned out to be a cruel rumor sparked by General Sherman’s policy in South Carolina of redistributing property from white plantation owners to enslaved men and women at the end of the war. Black and other political leaders pushed for nationalization of this policy throughout the confederate states, but it faced fierce opposition in Congress and never became part of federal law (History.com; McCurdy). The Freedmen’s Bureau, which was established by the U.S. government in 1865 to help the ex-slaves get land and other resources, was not the most effective agency. Seventy-seven percent of the applicants for land under the Southern Homestead Act, administered by the bureau, were white. All these applicants had to do to qualify for help from the Bureau was to swear that they had never taken up arms against the Union. (Oliver and Shapiro).

Property ownership had been the key to full citizenship ever since the first voting laws declared that only land-owning men could vote in the newly established United States of America. Even though voting laws had changed over the decades, property ownership was still seen as the absolute entrée to full participation in society. To many ex-slaves, land ownership was the key to enfranchisement and independence. Not only that, but ex-slaves could use skills and knowledge they had developed on plantations to supplement the meager foods and other resources doled out to them by the owners to become more fully self-reliant if only they could control some land. Many of them knew how to hunt both small and large game; how to fish; how to grow vegetables; how to identify and use edible and medicinal herbs. All these skills could be used to stave off starvation and death now that they had to provide for themselves entirely (Sitton and Conrad).

Sharecropping, a form of agricultural labor that left African Americans in straits almost as difficult as slavery became the rule for many ex-slaves who had owned or dreamed of owning their own land and being self-reliant. Many ex-slaves and their descendants were forced through intimidation or trickery to sell what land they had managed to accumulate to whites at ridiculously low prices. Uneducated in slavery, thoroughly destitute and intimidated, some had no choice but to become sharecroppers in perpetual debt to the owners of the cotton plantations where they lived and worked as enslaved people (History.com; Taylor; Oliver and Shapiro).

About 20 percent of blacks in the state did not choose urban life or managed to avoid becoming sharecroppers by taking part in an important early experiment in self-determination (Sitton and Conrad). The group of communities established by these African Americans came to be known as "freedom colonies."

Experiment in Self-Determination

From the late 1860s to the early twentieth century more than 400 freedom colonies were established in Texas. These small agricultural communities were an important early attempt at black self-determination. The freedom settlements showed how banding together to build churches, schools and community centers could provide a basic organizing model for black communities both rural and urban. The church was usually the first communal facility built in a settlement of ex-slaves, and ministers were often the community leaders (Smith; Sitton and Conrad). Ex-slaves throughout the South clung to their African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist and Colored (now Christian) Methodist Episcopal faiths, now that they could worship openly in their own congregations with their own leaders away from such restrictions as racially segregated seating.

Freedom colonies tended to be in remote areas on land that could support small farms but definitely not large cotton plantations. (Fletcher; Sitton and Conrad; Coppedge) It was felt that the further the fledgling communities were from established white towns, the safer they would be from prying eyes and white harassment. Often freedom colony residents were almost completely self-sustaining, going into larger towns only for staples that they could not produce themselves. Sometimes people simply squatted on vacant land and claimed it for their own. There were legal provisions that allowed squatters to claim land after living on it and working it for three years (Coppedge). Sometimes white ex-slave-owners lived in colonies with people who had been enslaved, so the white people could survive post-war catastrophes. Other times the ex-slave owners lived with the families they had started with enslaved people during slavery. Living in the colonies was the first time they could live openly with black and white family members together (Sitton and Conrad).

Weathered granite tablets in front of the St. John Regular Baptist Church relating the origin and the history of St. John Colony. Photo by Terry Jeanson

Vestiges of these freedom colonies can be found around the state today, but most of the colonies have not survived. One of the most picturesque sites is that of St. John Colony in Caldwell County near Lockhart founded in 1872. St. John Colony Missionary Baptist Church still stands and in front of it is the pink granite memorial slab bearing a description of the founding of the community and a frieze of the wagon train of the original settlers to the area on the other (Smith). The community was founded by the Rev. John H. Winn who searched for land for a settlement and finally arranged to buy 2,000 acres of forest land. When he returned to Webberville in Bastrop County where his community of 15 families waited, a wagon train was assembled, and everyone made the trip to St. John. Each family bought 25 to 100 acres and went to work clearing it and cultivating crops. The church was finished in 1873 and eventually the colony featured a sorghum mill, grocery stores, post office, cotton gin and grist mill, and a large hall. The school remained open until the arrival of school desegregation in the 1960s.(Smith) Now every year some of the few descendants of the original settlers of St. John Colony recreate and celebrate the arrival of their ancestors in a wagon train during Juneteenth holiday celebrations.

Juneteenth reunions and barbecues are often gatherings for descendants of the freedom colonists. Now, traces of the colonies can be seen in the remnants of schoolhouses, churches and other buildings as well as small cemeteries. A few of the communities were Pelham Colony, about 25 miles from Corsicana; The Colony in Hood County; Armstrong Colony in Fayette County; Peyton Colony in Blanco County; and Jakes Colony in Guadalupe County, which has a street sign. There were more than 45 freedmen’s settlements in Limestone County alone. A tradition there is a joint celebration of Juneteenth by all the descendants of the freedmen’s colonies at Comanche Crossing on the Navasota River (Coppedge; Fletcher; rootsweb.ancestry.com; lockhart.k12.tx.us; Sitton and Conrad; The Colony).

Juneteenth has become not only a meaningful day of remembrance and joy for descendants of members of the freedmen’s colonies, but a national community holiday in celebration of freedom.

Starita Smith, Ph.D., is an adjunct professor of sociology at North Carolina Wesleyan College, an occasional columnist for the Progressive Media Project and an activist.

Works Cited

Barr, Alwyn. The African Texans. Texas A&M University Press: College Station, TX. 2004. Print.

Bliss, Jillian. “Remnant of Austin African-American Neighborhood to Open as a Restaurant.” Reporting Texas. Web. Nov. 5, 2014.

Coppedge, Clay. “Separate Beginnings: Communities of Freed Slaves Grew into What Became Freedom Colonies and Some of Those Towns Remain on the Map.” Texas Electric Cooperatives. Oct. 2012. Web. June 12, 2014.

Fletcher, LaDawn. “Roads to Freedom.” Texas Highways: the Travel Magazine of Texas. July, 2011. Web. June12, 2014.

History.com. “Sharecropping.” History.com. 2010. Web. Nov. 7, 2014.

lockhart.k12.tx.us. “St. John Colony.” Feb. 26, 1998. Web. July 30, 2014.

McCurdy, Devon. “Forty Acres and a Mule.” BlackPast.org. Web. Nov. 7, 2014.

Oliver, Melvin L. and Thomas M. Shapiro. Black Wealth/White Wealth; A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. Routledge: New York City. 1995. Print.

“Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the state of Texas.” The Freedmen’s Bureau Online. Web. June 12, 2014.

rootsweb.ancestry.com. “Jakes Colony, Gualalupe, TX and the African Methodist Episcopal Church (A.M.E.)” Web. June 12, 2014.

Sanders, Brandee. “History’s Lost Black Towns.” theRoot. Jan. 27, 2011. Web. June 12, 2014.

Sitton, Thad and James H. Conrad. Freedom Colonies: Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow. University of Texas Press: Austin, TX. 2005. Print.

Smith, Starita. “Annual Ride Commemorates Trek of Freed Slaves to St. John Colony.” Austin American-Statesman. June 18, 1992. Web. June 12, 2014.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990. W.W. Norton & Co.: New York City. 1998. Print.

“The Colony.” Hood County Genealogical Society. Nov. 15, 1998. Web. June 12, 2014.

Thompson, Nolan. “Wheatsville, TX. (Travis County).” Handbook of Texas Online. June 10, 2010. Web. Nov. 6, 2014.

Washington, Reginald. “Sealing the Sacred Bonds of Holy Matrimony; Freedmen’s Bureau Marriage Records.” Prologue Magazine. Spring, 2005. Web. Nov. 5, 2014.