The Heroines of America’s Black Press

Image: A collage of the art commissioned for this article; from top left, by Johnalynn Holland, Andrea Pippins, Erin Robinson, Elise R. Peterson, Adriana Bellet, and Xia Gordon

(The New York Review of Books) How many black women journalists from the nineteenth century can you name? For many, the list starts and ends with Ida B. Wells, the pioneering newspaperwoman and activist whose anti-lynching crusade galvanized a movement. Wells was celebrated in her own lifetime, and for good reason—she inspired people on both sides of the Atlantic to pay attention to the atrocities inflicted on black Americans. But far from acting alone, she was part of a much larger network of black women journalists who dared to wield their pens in the names of truth and justice. At a time when all women were discouraged from engaging in “unladylike” activities like politics, the women of the black press were boldly writing about racial justice, gender equality, and political reform.

The African-American press of the nineteenth century was a lively, dynamic, insistently visible force for change. First emerging in 1827 with Freedom’s Journal, a New York–based newspaper founded by a group of free black men and edited by journalists Samuel Cornish and John Russworm, the initial pre-Emancipation black-owned papers not only railed against slavery and injustice but served as a vital source of community and education. They spread knowledge about current affairs, literature, and the arts, during a time when simply learning how to read and write in many parts of the country could get a black person killed. Countering the constant hatred leveled against black Americans by the mainstream press, and white America at-large, the publications provided a space for their readers to be truthfully, respectfully, seen.

Crucial to many of these publications was the exceptional work of black women. These journalists were of the black elite and the working class, the free-born and the formerly enslaved. They were a mix of wives and mothers and widows, and women who never married at all. They were civic workers and religious leaders and educators—and many of them were active clubwomen.

In an attempt to repair some of what’s been lost to time and prejudice, six different artists who celebrate black womanhood in their own work—Adriana Bellet, Andrea Pippins, Elise R. Peterson, Erin Robinson, Johnalynn Holland, and Xia Gordon—have created original portraits of the journalists described here, based on the images that are extant. These portraits, and the brief biographies that accompany them, honor the extraordinary lives these women led and serve to memorialize their legacies. (more)

2020 Aya Symposium at PVAMU has been canceled

Because of the coronavirus crisis, the 2020 Aya Symposium scheduled for June 5 at Prairie View, has been cancelled.

Because of the coronavirus crisis, the 2020 Aya Symposium scheduled for June 5 at Prairie View, has been cancelled.

However, please stay tuned as we plan for next year’s event which will include an engaging lineup of dynamic, engaging speakers and panelists, and informative breakout sessions.

Updates will be posted here in the TIPHC weekly newsletter.

You may also visit the event’s website: ayasymposium.org.

David Driskell, 88, Pivotal Champion of African-American Art, Dies

An artist himself, Professor Driskell recognized the role of black artists in the broader story of American art. He died of the coronavirus.

(New York Times) David C. Driskell, an artist, art historian and curator who was pivotal in bringing recognition to African-American art and its importance in the broader story of art in the United States and beyond, died on April 1 in a hospital near his home in Hyattsville, Md. He was 88.

(New York Times) David C. Driskell, an artist, art historian and curator who was pivotal in bringing recognition to African-American art and its importance in the broader story of art in the United States and beyond, died on April 1 in a hospital near his home in Hyattsville, Md. He was 88.

The University of Maryland, where he held the title of distinguished university professor of art, said in a posting on its website that the cause was the coronavirus.

Professor Driskell was teaching at Fisk University in Nashville in the mid-1970s when he began putting together “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950,” a landmark exhibition that was first mounted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and that later traveled to the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the Brooklyn Museum. (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

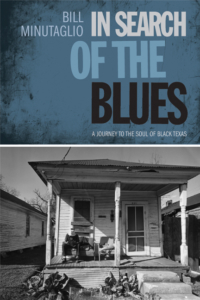

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “In Search of the Blues, A Journey to the Soul of Black Texas,” by Bill Minutaglio.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “In Search of the Blues, A Journey to the Soul of Black Texas,” by Bill Minutaglio.

The rich, complex lives of African Americans in Texas were often neglected by the mainstream media, which historically seldom ventured into Houston’s Fourth Ward, San Antonio’s East Side, South Dallas, or the black neighborhoods in smaller cities. When Bill Minutaglio began writing for Texas newspapers in the 1970s, few large publications had more than a token number of African American journalists, and they barely acknowledged the things of lasting importance to the African American community. Though hardly the most likely reporter—as a white, Italian American transplant from New York City—for the black Texas beat, Minutaglio was drawn to the African American heritage, seeking its soul in churches, on front porches, at juke joints, and anywhere else that people would allow him into their lives. His nationally award-winning writing offered many Americans their first deeper understanding of Texas’s singular, complicated African American history.

This eclectic collection gathers the best of Minutaglio’s writing about the soul of black Texas. He profiles individuals both unknown and famous, including blues legends Lightnin’ Hopkins, Amos Milburn, Robert Shaw, and Dr. Hepcat. He looks at neglected, even intentionally hidden, communities. And he wades into the musical undercurrent that touches on African Americans’ joys, longings, and frustrations, and the passing of generations. Minutaglio’s stories offer an understanding of the sweeping evolution of music, race, and justice in Texas. Moved forward by the musical heartbeat of the blues and defined by the long shadow of racism, the stories measure how far Texas has come . . . or still has to go.

This Week in Texas Black History

Apr. 5

A year before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Archbishop Robert Lucey announced on this day in 1953 that all of San Antonio’s parochial schools and the city’s two Catholic colleges would be integrated. Lucey, the second Catholic archbishop of San Antonio, was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 16, 1891. In 1950 his social activism became nationally known with his appointment to President Harry Truman’s Commission on Migratory Labor, and he continued to champion the poor of San Antonio. In 1953, following Lucey’s lead, officials of the San Antonio, El Paso, and Corpus Christi school districts integrated their schools. Lucey died on August 1, 1977.

A year before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Archbishop Robert Lucey announced on this day in 1953 that all of San Antonio’s parochial schools and the city’s two Catholic colleges would be integrated. Lucey, the second Catholic archbishop of San Antonio, was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 16, 1891. In 1950 his social activism became nationally known with his appointment to President Harry Truman’s Commission on Migratory Labor, and he continued to champion the poor of San Antonio. In 1953, following Lucey’s lead, officials of the San Antonio, El Paso, and Corpus Christi school districts integrated their schools. Lucey died on August 1, 1977.

Apr. 6

Jazz pianist and black activist Horace Tapscott was born this day in Houston in 1934. By age six he had become a competent pianist. His family moved to Los Angeles in 1943 and Tapscott began his career and would play with Lionel Hampton though primarily as a trombonist, and would be a member of Motown Records’ West Coast band, backing such groups as the Supremes. Tapscott founded the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra, also known as the Ark, a collective group dedicated to preserving and developing African-American musical traditions and promoting cultural and musical education. It also distributed free food to families in Watts and made available meeting space for black radicals such as Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Tapscott released fourteen albums.

Apr. 7

On this day in 1954, All-Pro running back Tony Dorsett was born in Rochester, Pa. At the University of Pittsburgh, Dorsett won the 1976 Heisman Trophy and was a first round pick (No. 2 overall) by the Dallas Cowboys in the 1977 NFL Draft. He was Offensive Rookie of the Year and in 1994 was inducted to both the Pro Football and College Football halls of fame. That same year, he was also enshrined in the Texas Stadium Ring of Honor. Dorsett rushed for 12,739 yards (8th all-time) and 77 touchdowns in his 12-year career. His 99-yard touchdown run on January 3, 1983 against the Minnesota Vikings is the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history. See the run here.

On this day in 1954, All-Pro running back Tony Dorsett was born in Rochester, Pa. At the University of Pittsburgh, Dorsett won the 1976 Heisman Trophy and was a first round pick (No. 2 overall) by the Dallas Cowboys in the 1977 NFL Draft. He was Offensive Rookie of the Year and in 1994 was inducted to both the Pro Football and College Football halls of fame. That same year, he was also enshrined in the Texas Stadium Ring of Honor. Dorsett rushed for 12,739 yards (8th all-time) and 77 touchdowns in his 12-year career. His 99-yard touchdown run on January 3, 1983 against the Minnesota Vikings is the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history. See the run here.

Apr. 9

On this day, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 became effective, granting citizenship and the same rights enjoyed by white citizens to all male persons in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” President Andrew Johnson‘s veto of the bill was overturned by a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, and the bill became law.

Apr. 9

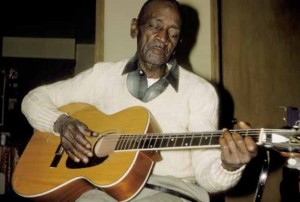

On this day in 1895, blues singer and guitarist Bowdie Glenn Lipscomb was born in Navasota. As a youngster, Lipscomb would take the name “Mance,” short for “Emancipation,” the name of an elder family friend. Lipscomb, who preferred to be known as a “songster” because of the variety of songs he sang, was discovered and first recorded in 1960 during the country blues revival. The annual Navasota Blues Festival is held in his honor. A bronze sculpture of him was unveiled in Mance Lipscomb Park in Navasota on 2011.

Apr. 10

Golfer Lee Elder, a Dallas native, became the first African-American to play in the Masters Tournament on this day in 1975. Leading to the tournament, Elder endured hate mail that said he would never make it to Augusta and that he should “watch your step when you get to Augusta,” and that “there will be blood.” Undaunted, Elder competed in the tournament, but missed the cut after shooting 152 (8-over par) for the first two rounds.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

For every beginning there’s an end

To live is to die. Every beginning has an end. That’s not a very pleasant way to begin, but as Believers we are on a journey that ends with the grave. As a child I watched my mother deal with her mother as she entered the last chapters of her life. I didn’t fully understand what was going on, but I remember my mother assisting my grandmother to her various appointments. As life would…(more)

Lessons from Saturday Morning

One of my fondest memories from childhood is Saturday morning cartoons. That was the only time of the week I gladly woke up at 7 a.m. I remember rushing in my pajamas to that big(?) 19” TV to watch Bugs Bunny and Super Friends. Sometimes my mother would sit with me. But I remember not really wanting her watching cartoons with me. Its not that I didn’t enjoy my mother’s company, because I did. (more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.