Bass Reeves Finally Gets His Hollywood Moment in HBO’s ‘Watchmen’

The legend of the former Texas marshal figures prominently in Damon Lindelof’s new series.

Photo credit: ilbusca/Getty, Public Domain

(Texas Monthly) The series premiere of HBO’s Watchmen opens with a black-hooded figure in hot pursuit of a lawman; he quickly finds himself lassoed in front of a stunned church congregation. So far, so Watchmen. But then, the cloaked man reveals himself to be the legendary Bass Reeves—the real-life, first black deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi—and he then exposes his hogtied quarry as the corrupt white sheriff who’s been rustling all the local cattle. “He doesn’t deserve the badge,” Reeves (played by Jamal Akakpo) tells the grateful townspeople, who cheer as this vigilante liberates them from a villain who’d disguised himself as their protector.

The scene, rendered in the style of an old silent movie, offers a distillation of the major questions posed by both the series and the acclaimed graphic novel it’s based on: Who gets to be a “hero”? What actually motivates them? And most importantly, why should we trust them?

As in the book, Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen show offers an uneasy blur of historical fact and comic fiction, existing in an alternate timeline that deviates from our own with details both minor and cosmically significant. As we’re watching Reeves’s movie-within-a-movie, the camera pulls back to reveal a black child watching this very scene raptly inside a theater, his idyll suddenly broken by an eruption outside: The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, in which white mobs attacked the black neighborhoods of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street,” slaughtering dozens of people, injuring scores more, and burning their homes and businesses to the ground.

In the show, as in the United States, racial violence lies at the root of tensions that still simmer today. Watchmen’s nation, much like ours, is bitterly and politically divided, with fascism on the rise and white supremacists rearing their ugly heads. Except in Watchmen, both the racists and the cops wage war from behind masks, superheroes are real, and the idea of who “deserves the badge” is a constant struggle. (Also, Robert Redford is the president and squids occasionally fall from the sky.)

Although he was never a movie hero, Reeves was a real person whose exploits often verged on the fantastical. (more)

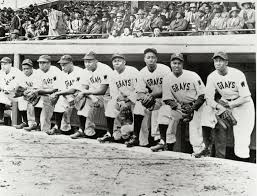

Washington’s last World Series team was not the Senators. It was a Negro League dynasty.

The 1946 Homestead Grays stand at their dugout at Griffith Stadium in Washington. (Negro Leagues Baseball Museum)

(The Washington Post) There was no celebration the last time a Washington baseball team won a World Series. No parade, no championship rings, no trophy awarded to the victor. One team couldn’t host games on its home field. The series took 10 days, and players on the road were prohibited from staying in the host city’s finest hotels.

The Washington Senators last won Major League Baseball’s World Series in 1924 against the New York Giants, four games to three. They went back to the championship round in 1933 but lost to New York, this time in five games.

But Washington’s last World Series team was the 1948 Homestead Grays, who defeated the Birmingham Black Barons, four games to one, to cap perhaps the most dominant stretch of baseball in American history. (more)

Princeton Theological Seminary approves reparations

(The Princetonian) On Oct. 18, Princeton Theological Seminary announced its plans to finance reparations, making it the second theological institution in the nation, after Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Va., to do so.

The decision, unanimously approved by the Seminary’s trustees, comes as an official response to a historical audit, commissioned in 2016, which examined the Seminary’s historical participation in the institutions of American slavery.

Since the report was commissioned, Princeton Theological Seminary has witnessed significant student activism, particularly by the Seminary’s Association of Black Seminarians (ABS), whose members have called for the Seminary to approve and disburse reparations. (more)

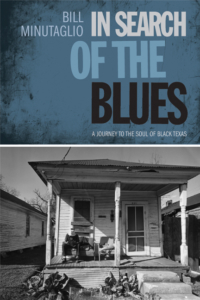

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “In Search of the Blues, A Journey to the Soul of Black Texas,” by Bill Minutaglio.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “In Search of the Blues, A Journey to the Soul of Black Texas,” by Bill Minutaglio.

The rich, complex lives of African Americans in Texas were often neglected by the mainstream media, which historically seldom ventured into Houston’s Fourth Ward, San Antonio’s East Side, South Dallas, or the black neighborhoods in smaller cities. When Bill Minutaglio began writing for Texas newspapers in the 1970s, few large publications had more than a token number of African American journalists, and they barely acknowledged the things of lasting importance to the African American community. Though hardly the most likely reporter—as a white, Italian American transplant from New York City—for the black Texas beat, Minutaglio was drawn to the African American heritage, seeking its soul in churches, on front porches, at juke joints, and anywhere else that people would allow him into their lives. His nationally award-winning writing offered many Americans their first deeper understanding of Texas’s singular, complicated African American history.

This eclectic collection gathers the best of Minutaglio’s writing about the soul of black Texas. He profiles individuals both unknown and famous, including blues legends Lightnin’ Hopkins, Amos Milburn, Robert Shaw, and Dr. Hepcat. He looks at neglected, even intentionally hidden, communities. And he wades into the musical undercurrent that touches on African Americans’ joys, longings, and frustrations, and the passing of generations. Minutaglio’s stories offer an understanding of the sweeping evolution of music, race, and justice in Texas. Moved forward by the musical heartbeat of the blues and defined by the long shadow of racism, the stories measure how far Texas has come . . . or still has to go.

This Week in Texas Black History

Oct. 27

On this day in 2002, Dallas Cowboys’ running back Emmitt Smith passed Chicago Bears great Walter Payton and became the National Football League’s all-time rushing leader on an 11-yard gain in the fourth quarter of the Cowboys’ 17-14 loss to the Seattle Seahawks in Dallas. Smith retired two years later with 18,355 career yards to Payton’s 16,726. Smith, who played collegiately at the University of Florida, was the Cowboys first round pick (number 17 overall) in the NFL’s 1990 draft. He played in eight Pro Bowls and was a four-time first-team All-Pro. In 2005, Smith was inducted to the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor and in 2010 he was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

On this day in 2002, Dallas Cowboys’ running back Emmitt Smith passed Chicago Bears great Walter Payton and became the National Football League’s all-time rushing leader on an 11-yard gain in the fourth quarter of the Cowboys’ 17-14 loss to the Seattle Seahawks in Dallas. Smith retired two years later with 18,355 career yards to Payton’s 16,726. Smith, who played collegiately at the University of Florida, was the Cowboys first round pick (number 17 overall) in the NFL’s 1990 draft. He played in eight Pro Bowls and was a four-time first-team All-Pro. In 2005, Smith was inducted to the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor and in 2010 he was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Oct. 28

English and Speech Professor Melvin Tolson organized the Forensic Society of Wiley College on this day in 1924. The debate teams compiled a ten-year winning streak. Tolson wrote the team’s speeches and the debaters memorized them with Tolson training them on every gesture and pause. He anticipated opponents’ arguments and wrote rebuttals before the actual debates. The 1935 team won the national championship, defeating the University of Southern California. The story of that team and Tolson’s leadership were the subjects of the 2007 film “The Great Debaters.”

English and Speech Professor Melvin Tolson organized the Forensic Society of Wiley College on this day in 1924. The debate teams compiled a ten-year winning streak. Tolson wrote the team’s speeches and the debaters memorized them with Tolson training them on every gesture and pause. He anticipated opponents’ arguments and wrote rebuttals before the actual debates. The 1935 team won the national championship, defeating the University of Southern California. The story of that team and Tolson’s leadership were the subjects of the 2007 film “The Great Debaters.”

Oct. 29

E.H. Anderson, Prairie View State Normal School principal, died on this day in 1885. Anderson, a native of Memphis, had become the school’s second principal in 1879.

E.H. Anderson, Prairie View State Normal School principal, died on this day in 1885. Anderson, a native of Memphis, had become the school’s second principal in 1879.

Oct. 30

On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy – leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy – leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

Oct. 30

On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

Oct. 31

On this day in 1835 a volunteer company was formed in Huntsville, Ala. to travel to Texas and help fight in the Texas Revolution against Mexico. A free black, Peter Allen, a flutist, was welcomed into the company as a musician. Allen, a native of Philadelphia, Pa. was the son of Richard Allen, founder and first Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. On March 20, 1836, Allen and his company, approximately 300 men commanded by Col. James Walker Fannin, participated in the Battle of Coleto Creek, but the men were forced to surrender and were imprisoned at Goliad. A week later, on Palm Sunday, all of the men were executed and their bodies burned in what became known as the Goliad Massacre. Asked by the Mexican commander to play a tune in exchange for his freedom, Allen refused and was also executed. Reportedly, Allen had responded to the request by saying, “No, I’ll not play, but I’ll just go along with the rest of the boys.”

Oct. 31

State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

Oct. 31

Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

Nov. 1

In 1903, on this day, Houston music impresario Don Robey was born. Robey was influential in developing the Texas blues scene, but he also produced major gospel talents. Robey’s music business empire included several music labels, most prominent being Peacock Records, and his was likely the first such enterprise run by an African-American. Robey produced dozens of blues and gospel artists, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Mighty Clouds of Joy.

Nov. 2

On this day in 1963, the Baylor University Board of Trustees voted to integrate the school, the world’s largest Baptist institution of higher learning. Hilton E. Howell, chairman of the board, said, “The action of the Baylor University Board of Trustees was taken after full and free discussion. While the final vote of the board adopting the new policy was not unanimous, the decision was reached by amicable discussion and democratic procedure.”

Nov. 2

On this day in 1999, legendary Prairie View A&M football coach Billy Nicks passed away in Houston at age 94. Nicks was a native of Griffin, Ga. and attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. As a coach, his 1941 Morris Brown team was named black college national champion, but it would be in Texas, at Prairie View, where Nicks would make his mark as one of the top coaches in college football history. He began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC opponent, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. Nicks’ overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. He is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Football is still football

October 14th, 2019

Since we’re into the football season I thought it was time to interject my two cents. I’ve noticed several teams starting black quarterbacks these days. Some because of injury, but others have been under center since training camp. By my count, the first weekend of the National Football League season in September saw nine African…(more)

1960s Revisited

Over the last few years our society has spent a great amount of energy reliving and analyzing the 1960s. Every event – from the deaths of the Kennedy brothers, MLK and Malcolm X, landing on the moon, war protests, and the hippie revolution – has been scrutinized through the microscope of history. The interesting thing about history’s microscope, though, is that it often blots out the nasty and the ugly. The concept of revisionism centers…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.