In rural Texas, black students’ fight for voting access conjures a painful past

Photo: Even after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the ratification six years later of the 26th Amendment, lowering the voting age to 18, Prairie View students faced barriers, including a “residency questionnaire” in the 1970s and charges of improper voting in the 1990s. (Melina Mara/The Washington Post)

(The Washington Post ) First came the poll taxes and whites-only primaries that targeted African Americans in this southeastern Texas community.

In more recent decades, students at the historically black Prairie View A&M University were required to complete a “residency questionnaire” to prove their eligibility to vote. They saw their power at the ballot box diluted when their campus was carved into separate districts. Some were arrested when they tried to cast ballots, accused of improper voting.

Then came the 2018 midterm elections, when county leaders scheduled fewer early-voting hours on the university campus than in whiter communities nearby.

“Here we go again,” Jayla Allen, a third-generation Prairie View student, thought angrily at the time. She and other students sued, determined to fight what they viewed as racial injustice just as others had done in the past, she said.

Freighted with centuries’ worth of mistreatment of African Americans, the debate over Waller County’s election practices has emerged as a battle about more than just voting hours. The relatively narrow dispute has tapped into deep feelings of marginalization and anger over long-standing efforts to keep black voters from the polls.

The intensity of the reaction in Prairie View echoes discussions across the country about racial inequality, which are prompting new examinations of past injustice to understand the present. (more)

How a Bus Tour Helps Illuminate Dallas’ Black History, Hidden in Plain Sight

Don and Jocelyn Pinkard spend their days researching the history that Dallas has paved over. They want to take you to it.

A home in State Thomas, one of the few remaining from when this neighborhood was a Freedman’s Town in North Dallas. (Photo by Daniel Estevao)

(D Magazine) Dallas projects itself as a swaggering, self-made city destined for greatness. It proudly proclaims to have no limits, no reason to be and no history. But there is a history hidden in plain sight.

It is hidden because Dallas plowed through the city’s first and largest African American cemetery to build the North Central Expressway in the 1940s. It is hidden because Dallas history books, like Jim Schutze’s The Accommodation, get blocked by publishers at the risk of embarrassing city leadership. Neighborhoods change at warp speed. Historic buildings stand empty and neglected, if they still stand at all.

Stories get buried and replaced with myths of a white male business elite that created a regional economic empire out of nothing. The old white leadership controlled official memory for decades through a combination of the pulpit, news media, school curricula, entertainment, architecture, and urban renewal. But today, academics and curious residents are creating a more accurate history that includes the human costs of Dallas’ development.

Now retired, Don and Jocelyn Pinkard spend their days researching scarcely discussed stories of Dallas’ past for their Hidden History DFW tour. Visitors travel the city to more than 20 historic African American sites before lunch. The Pinkards and their families go back generations in Texas. Having both been raised in Oak Cliff, they have firsthand knowledge of the city and its many transformations. And they are sharing it. (more)

They were once sent home for their Olympic protest. Now they’ll get the USOPC’s highest honor.

John Carlos, left, and Tommie Smith pose in 2018 on the campus of San Jose State University. (Tony Avelar/AP)

(The Washington Post) Nearly 51 years after the organization expelled Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the Summer Olympics, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee is bestowing its highest honor on two of the sports world’s most iconic activists.

The sprinters highlight the USOPC Hall of Fame’s latest induction class and will be formally honored at a ceremony Nov. 1 in Colorado Springs, the organization announced Monday. This year’s inductees also include basketball player Lisa Leslie, gymnast Nastia Liukin, beach volleyball player Misty May-Treanor, speedskater Apolo Anton Ohno, swimmer Dara Torres and the 1998 U.S. Olympic women’s ice hockey team.

The organization’s hall of fame was established in 1979. It has been dormant for stretches; this year marks the first induction class since 2012 and the 16th overall.

Smith and Carlos were responsible for one of the most recognizable moments in Olympic history, raising their fists in protest on the medal podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics. (more)

Despite Obstacles, Black Colleges Are Pipelines to the Middle Class, Study Finds. Here’s Its List of the Best.

PVAMU ranked in top 10, based on the study of 50 HBCUs

An embryology class at Xavier U. of Louisiana. Seventy-nine percent of low-income students at the historically black university end up reaching the middle class, tops among HBCUs. (Brian Finke, Redux)

(The Chronicle of Higher Education) Historically black colleges and universities have far smaller endowments and a far larger share of low-income students than predominantly white institutions do. Yet black colleges raise students up the ladder of economic success at rates comparable to white colleges, according to a study to be released on Monday by the Rutgers Center for Minority Serving Institutions.

A report on the study, drawing on data from the Opportunity Insights project at Harvard University, compared the trajectories of students who attended 50 HBCUs against those who went to mostly white institutions in the same regions. Two-thirds of HBCU students from low-income families, meaning those with household incomes of roughly $25,000 or less, ended up earning at least middle-class incomes by their early to mid-30s. Seventy percent of low-income students at mostly white colleges reached the middle class or higher by that age, according to the report, “Moving Upward and Onward: Income Mobility at Historically Black Colleges and Universities.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

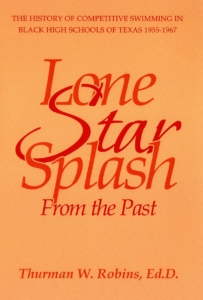

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Lone Star Splash, The History of Competitive Swimming in Black High Schools of Texas, 1955-1967,” by Thurman W. Robins, Ed.D.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Lone Star Splash, The History of Competitive Swimming in Black High Schools of Texas, 1955-1967,” by Thurman W. Robins, Ed.D.

In the Lone Star State, during the era of segregation, competitive swimming and diving for both boys and girls were introduced in four black high schools. These four black high schools competed in the first district swimming meet at Central High School in Galveston, Texas, in the spring of 1955. Over a thirteen-year period, performances in every event improved significantly. In 1966, the last season prior to integration, seven teams competed for district and state honors.

Phillis Wheatley of Houston claimed the first three district championships, followed by Jack Yates, who won five consecutive championships. Booker T. Washington High School Houston claimed the last five district championships and three state championships.

Both boys and girls competed for the city/district championships in the four competitive strokes plus fancy diving. Many individuals who competed in the high school programs earned collegiate swimming scholarships at HBCUs all of America.

This Week in Texas Black History

Oct. 3

On this day in 2014, Dallas businessman and philanthropist Comer Cottrell passed away from natural causes. A native of Mobile, Ala., Cottrell founded Pro-Line, hair care products for African-Americans, in Los Angeles in 1970. He is noted for popularizing the “Jheri curl“. In 1980, he relocated the business to Dallas where it became the largest black-owned firm in the Southwest and one of the most profitable black companies in the United States. Cottrell was the first black member of the powerful Dallas Citizens Council and became part owner of Texas Rangers baseball team in 1989, becoming the first African-American to hold such a stake in a Major League Baseball team.

Oct. 3

Heman Sweatt, whose landmark case against the University of Texas Law School in 1950 set a precedent for Brown v. Board of Education and the integration of all public schools in the U.S., died on this day in 1982 in Atlanta, Ga. Sweatt, was born in Houston and graduated from Jack Yates High School and then Wiley College. Before his attempts to enter UT, he studied biology at the University of Michigan with intentions of entering medical school. After resolution of his case, Sweatt attended the school for two years, but the emotional and physical toll from his quest forced him to leave school. He received a scholarship to study social work at Atlanta University and earned a master’s degree in community organizations in 1954. He later became assistant director of the National Urban League‘s southern regional office in Atlanta.

Oct. 4

Born on this day in 1937 in Wewoka, Oklahoma (southeast of Oklahoma City), Lee Patrick Brown was the first African-American police chief and then the first African-American mayor for the city of Houston. Brown’s parents were sharecroppers and moved to San Jose, California where he began his law enforcement career as a police officer while a student at San Jose State University. There, he earned degrees in criminology (1960) and sociology (1964 – master’s). He also earned a master’s and then a doctorate in criminology from the University of California-Berkeley. Brown was the first African-American police for three cities: Atlanta (1978), Houston (1982), and New York City (police commissioner, 1990). In Atlanta, he was chief during the Atlanta child murders case which resulted in the arrest and conviction of Wayne B. Williams. In Houston, Brown pioneered the community policing concept that included officers patrolling neighbors on foot. In 1993, he was appointed director of the White House Office of Drug Control Policy, and in 1997 was elected mayor of Houston and served three two-year terms.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

1960s Revisited

Over the last few years our society has spent a great amount of energy reliving and analyzing the 1960s. Every event – from the deaths of the Kennedy brothers, MLK and Malcolm X, landing on the moon, war protests, and the hippie revolution – has been scrutinized through the microscope of history. The interesting thing about history’s microscope, though, is that it often blots out the nasty and the ugly. The concept of revisionism centers…(more)

We owe them reverence

Given the infinite nature of the Universe, four hundred years is merely a blink of the eye. But the human existence is not infinite. We understand that from the moment we take our first breath out of our mothers’ wombs, our journey begins towards that moment when we take our last breath. So, for us whose existence is finite, we consider four hundred years a mighty long time. We really know very little about those…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.