The Photos That Lifted Up the Black Is Beautiful Movement

For over 50 years, the photographer Kwame Brathwaite captured African-American beauty and fashion, giving visual power to black power.

Image: Untitled (Photo shoot at a school for one of the many modeling groups who had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s), 1966. Credit: Kwame Brathwaite/Courtesy of Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

(The New York Times) The intersection of West 125th Street and Seventh Avenue in Harlem was, for decades, a center of black nationalism. Street orators — that’s what they were called — climbed onto stepladders and made impassioned calls for African liberation.

When Kwame Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath were teenagers in the 1950s, they would walk there from their dad’s dry cleaning shop and listen, entranced, for hours. Mr. Brath once recounted the story of Carlos Cooks, a student of Marcus Garvey, bellowing to a black woman walking by: “Your hair has more intelligence than you. In two weeks, your hair is willing to go back to Africa and you’ll still be jivin’ on the corner.” (Two weeks was just about how long hot-combed styles kept a black woman’s hair straight.)

After a few years of standing rapt at that corner, the brothers helped found the African Jazz Art Society and Studios, an artist collective also known as AJASS. The group produced concerts “to promote awareness of African-derived black music and dance forms,” Tanisha C. Ford, a historian, wrote in her book “Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul.”

It was with AJASS that Mr. Brathwaite started his career in photography, taking pictures first of the artists at the shows and then of residents of Harlem generally. AJASS later expanded its arts activism to include the Grandassas — black women the group recruited to model. Black women with kinky hair, full lips, dark skin, and curvy bodies. Black women who could show other black women that blackness was something to take pride in.

Kwame Brathwaite documented them all. (more)

From slavery to possible sainthood: The story of America’s first black Catholic priest

Augustus Tolton’s miraculous journey has inspired a canonization effort and a one-man play

(The Washington Post) The story of America’s first black Catholic priest begins with a miraculous escape from slavery in 1862.

(The Washington Post) The story of America’s first black Catholic priest begins with a miraculous escape from slavery in 1862.

Augustus Tolton, who is now being considered for sainthood by the Catholic Church, was born enslaved in Missouri in April 1854. His parents, Peter and Martha Tolton, had him baptized Catholic, the faith of the family that owned them.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Peter Tolton ran away to join the Union Army. Months later, Martha Tolton also fled with her three children, Augustus, Charles and Anne — a bid for freedom that nearly ended in capture.

When they made it safely across the (Mississippi River) to freedom in Illinois, Martha Tolton broke down and cried. In Illinois, they got directions to the small settlement of Quincy, where they joined a Catholic church. Tolton’s mother took him to a Catholic school and asked the priest to allow Augustus to study there.

“He was initially welcomed into one of the Catholic schools,” (actor, Jim) Coleman said in an interview, “but he was kicked out because parishioners didn’t want a negro child in the school.”

A priest, Father Peter McGirr, was impressed by Tolton’s intelligence and mentored him, teaching him Latin and Greek. He encouraged Tolton to enter the priesthood.

“McGirr promised Augustus he would be educated,” Coleman said. “He wrote letters in the U.S. to get Augustus into a seminary. None accepted him because of his race. Then Father McGirr wrote letters to Rome, saying this individual was brilliant.” (more)

San Marcos’ First African-American Church Is Now A Historic Landmark

(Texas Standard) The San Marcos City Council has voted unanimously to designate the city’s first African-American church as a historic landmark. It was burned down in 1873 by the Ku Klux Klan and took almost three decades to rebuild. KUT’s DaLyah Jones has more:

(Texas Standard) The San Marcos City Council has voted unanimously to designate the city’s first African-American church as a historic landmark. It was burned down in 1873 by the Ku Klux Klan and took almost three decades to rebuild. KUT’s DaLyah Jones has more:

The church was built in 1866 in a historically black neighborhood, and served as the religious and social center for black people in San Marcos. The historical designation comes after San Marcos won a $150,000 preservation grant last month to restore the church, which has been vacant since 1986. Josie Falletta is with the city of San Marcos:

“It’s a really beautiful story because they’ve included the members of the original congregation in this conversation. They’ve included the Calaboose African American History Museum, which is directly across the street, in the conversation. So, there’s been a lot of community input and buy-in in the process, which is pretty amazing.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

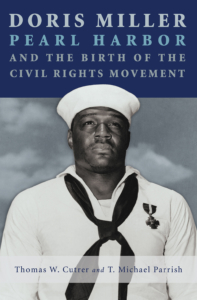

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Doris Miller, Pearl Harbor, and the Birth of the Civil Rights Movement,” by Thomas W. Cutrer and T. Michael Parrish.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Doris Miller, Pearl Harbor, and the Birth of the Civil Rights Movement,” by Thomas W. Cutrer and T. Michael Parrish.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, after serving breakfast and turning his attention to laundry services aboard the USS West Virginia, Ship’s Cook Third Class Doris “Dorie” Miller heard the alarm calling sailors to battle stations. The first of several torpedoes dropped from Japanese aircraft had struck the American battleship. Miller hastily made his way to a central point and was soon called to the bridge by Lt. Com. Doir C. Johnson to assist the mortally wounded ship’s captain, Mervyn Bennion. Miller then joined two others in loading and firing an unmanned anti-aircraft machine gun—a weapon that, as an African American in a segregated military, Miller had not been trained to operate. But he did, firing the weapon on attacking Japanese aircraft until the .50-caliber gun ran out of ammunition. For these actions, Miller was later awarded the Navy Cross, the third-highest naval award for combat gallantry.

Historians Thomas W. Cutrer and T. Michael Parrish have not only painstakingly reconstructed Miller’s inspiring actions on December 7. They also offer for the first time a full biography of Miller placed in the larger context of African American service in the United States military and the beginnings of the civil rights movement.

Like so many sailors and soldiers in World War II, Doris Miller’s life was cut short. Just two years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Miller was aboard the USS Liscome Bay when it was sunk by a Japanese submarine. But the name—and symbolic image—of Dorie Miller lived on. As Cutrer and Parrish conclude, “Dorie Miller’s actions at Pearl Harbor, and the legend that they engendered, were directly responsible for helping to roll back the navy’s then-to-fore unrelenting policy of racial segregation and prejudice, and, in the chain of events, helped to launch the civil rights movement of the 1960s that brought an end to the worst of America’s racial intolerance.”

This Week in Texas Black History

Dec 5

On this day in 1972, Austin musician Kenny Dorham died of kidney failure at age 48 in New York City. Dorham was one of the great trumpet pioneers of the bebop era, and worked with many of the bebop giants in the ’40s and ’50s, including Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, and Thelonious Monk.

On this day in 1972, Austin musician Kenny Dorham died of kidney failure at age 48 in New York City. Dorham was one of the great trumpet pioneers of the bebop era, and worked with many of the bebop giants in the ’40s and ’50s, including Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, and Thelonious Monk.

Dec 5

Willie M. “Bill” Pickett, the cowboy known as the “Dusky Demon” and inventor of the rodeo sport of bulldogging (steer wrestling), was born on this day in 1870 in Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, Pickett was the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

Willie M. “Bill” Pickett, the cowboy known as the “Dusky Demon” and inventor of the rodeo sport of bulldogging (steer wrestling), was born on this day in 1870 in Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, Pickett was the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

Dec 6

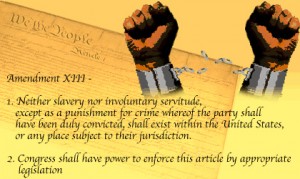

The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified by three-fourths of the states on this day in 1865, officially becoming part of the U.S. Constitution. The amendment declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” However, when the newly elected 11th Texas Legislature met in August 1866, the members refused to ratify either the 13th or 14th Amendment (granting citizenship to African Americans). The legislature wanted to return Texas as much as possible to the way it was before the war and restrict the rights of African Americans. Texas would not ratify the 13th amendment until February 18, 1870. Mississippi would be the last state to comply, ratifying the amendment in 1995, but the state didn’t officially notify the U.S. Archivist until 2012, when the ratification finally became official.

The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified by three-fourths of the states on this day in 1865, officially becoming part of the U.S. Constitution. The amendment declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” However, when the newly elected 11th Texas Legislature met in August 1866, the members refused to ratify either the 13th or 14th Amendment (granting citizenship to African Americans). The legislature wanted to return Texas as much as possible to the way it was before the war and restrict the rights of African Americans. Texas would not ratify the 13th amendment until February 18, 1870. Mississippi would be the last state to comply, ratifying the amendment in 1995, but the state didn’t officially notify the U.S. Archivist until 2012, when the ratification finally became official.

Dec 7

Publisher Julius Carter was born this day in 1914 in Houston. Carter founded the Forward Times newspaper in 1960 when segregation was in full force in Houston. Carter realized his vision of the Forward Times becoming a voice for the city’s African-American community.

Publisher Julius Carter was born this day in 1914 in Houston. Carter founded the Forward Times newspaper in 1960 when segregation was in full force in Houston. Carter realized his vision of the Forward Times becoming a voice for the city’s African-American community.

Dec 7

Philanthropist and founder of Pro-Line Corporation, maker of black hair products, Comer Cottrell, Jr., was born on this day in 1931 in Mobile, Alabama. Cottrell founded Pro-Line in Los Angeles in 1970, but relocated the business to Dallas in 1980. Pro-Line became the largest black-owned firm in the Southwest and one of the most profitable black companies in the United States. He is noted for popularizing the “Jheri curl” hairstyle. Cottrell became part owner of Texas Rangers baseball team in 1989, becoming the first African-American to hold such a stake in a Major League Baseball team and was also the first black member of the powerful Dallas Citizens Council.

Dec 7

On this day in 1941, Navy messman Doris Miller, a Waco native was aboard the USS West Virginia when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Miller moved several wounded sailors to safety and then manned an anti-aircraft gun, for which he had no training (because the Navy limited black sailors to non-combat roles and menial duties), and fired at attacking planes. For his actions, Miller was the first African-American to be awarded the Navy’s second highest honor, the Navy Cross.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Uncommon integrity

I, (NAME), do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the…(more)

Democratic hypocrisy

Democracy (noun) – The belief in freedom and equality between people, or a system of government based on this belief, in which power is either held by elected representatives or directly by the people themselves. — Cambridge Dictionary Over a hundred years ago W.E.B. Dubois asked if one could be black and an American. He saw this “twoness” as perhaps the central issue affecting all Africans in America. Personally, I also feel a unique identity crisis…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.