Historic black neighborhoods disappear all the time. But they don’t have to.

Houston takes center stage in a movement to preserve communities of color

Image: The Whole Foods Market 365 mural reflects Independence Heights’ roots. (Photo: Yi-Chin Lee, Staff photographer)

(Houston Chronicle) This week, Houston takes center stage in a national movement to preserve communities of color. A three-day conference will culminate November 3 with the inaugural celebration and ribbon cutting ceremony to kick off the North Main Street Heritage Corridor Initiative in Independence Heights, where artists will draw sketches of seven planned murals that will tell the story of the first African American municipality in Texas.

“The theme of the 2018 Preserving Communities of Color Conference is Disruptive Inspiration,'” says Tanya Debose, a lead organizer of the conference. “Speakers will share their stories of disruption turned inspiration and how they work at the grassroots level to preserve and revitalize their communities.”

The visibility of Independence Heights recently got a boost when Whole Foods agreed to work with the community on a mural painted on the new 365 Independence Heights store at the intersection of Yale Street and the 610 Loop. The muralist, Danny Asberry El, has family roots in the neighborhood, which was annexed by Houston in 1929. The site of the Whole Foods borders the historic Starkweather district. The seven additional murals will extend through several sites within Independence Heights. (more)

The Real Origins of Birthright Citizenship

Its purpose 150 years ago was to incorporate former slaves into the nation.

John A. Madison, left, great-grandson of African-American slave Dred Scott, points out his ancestor’s unmarked grave to his wife, Marcy, son John and daughter Lynn, at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Mo., Feb. 22, 1957. Scott died in 1958, only a year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled he was not a free man despite four year’s residence in free territory. Far-reaching effects of the decision made the Civil War inevitable. Scott’s grave is scheduled to receive its first marker this year, the 100th anniversary of the historic decision that split the nation. (AP Photo/J.M. Hogan)

(The Atlantic) Birthright citizenship just might be, former slaves believed, the safeguard they needed. In the decades before the Civil War, in an era when a remedy like the Fourteenth Amendment was hard to imagine, free black Americans embraced the view that they were citizens by virtue of having been born on U.S. soil. It was a lofty claim, especially because the Constitution was largely silent on the matter of who was a citizen and who was not. But for those who were descended from bondspeople, their circumstances were dire. Law and policy appeared to be conspiring against them, aimed directly at their tentative claims to belonging to the nation. Colonization societies organized to entice former slaves to migrate away, to Canada, the Caribbean, or Liberia in West Africa. Black laws restricted everyday life—work, travel, worship—to such a degree that black men and women felt squeezed out and many considered self-deportation.

In the U.S., birthright citizenship begins here, in the struggles of the marginalized and the despised to make this nation their own even as so many claimed that when it came to rights, it was a white man’s country. Most notorious among such denials of black citizenship was the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in Scott v. Sandford, often referred to as the Dred Scott case. But African Americans saw Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and his decision coming from years away. They had encountered his view—that black people had no rights that white men were bound to respect—in Congress and state courts, in newspaper columns and political conventions. They denounced Taney and the high court, gathering in meeting halls and churches to decry the denial of their birthright. And they never deferred to it. Taney’s decision was another round in a struggle that would take them to the Civil War and beyond. (more)

The Black Texas Congresswoman Who Took On Nixon

Sen. Barbara Jordan in July 1974, during a hearing on the impeachment of President Richard Nixon. (SOURCE: KEYSTONE/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY)

(OZY) It’s still considered one of the great American political speeches. “My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total,” Barbara Jordan thundered. “‘We, the people.’ I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.”

Jordan, a Black congresswoman in a pink suit and thick glasses, acknowledged that when the Constitution was drafted she wouldn’t have been included in that solemn promise. But on July 25, 1974, she delivered those words on national television, a staunch defense of Congress’ right to seek the impeachment of President Richard Nixon.

The speech pushed Barbara Jordan into the national limelight in the same way that Barack Obama’s keynote address at the Democratic National Convention rocketed him to fame in 2004. Jordan was a rumored candidate to be Jimmy Carter’s running mate and became the first African-American woman to deliver a keynote address at the DNC in 1976. But like many Black women who changed the world, her seemingly overnight success was the product of countless smaller victories. And as women of color rise, from Kamala Harris, the first Indian-American (and Jamaican-American) senator, to Stacey Abrams, who is vying to become the nation’s first elected female African-American governor, lessons can be learned from Jordan’s legacy. (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

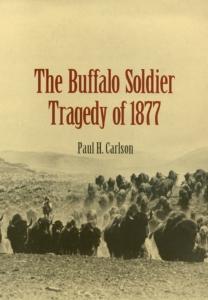

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877,” by Paul H. Carlson.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Buffalo Soldier Tragedy of 1877,” by Paul H. Carlson.

In the middle of the arid summer of 1877, a drought year in West Texas, a troop of some forty buffalo soldiers (African American cavalry led by white officers) struck out into the Llano Estacado from Double Lakes, south of modern Lubbock, pursuing a band of Kwahada Comanches who had been raiding homesteads and hunting parties. A group of twenty-two buffalo hunters accompanied the soldiers as guides and allies.

Several days later three black soldiers rode into Fort Concho at modern San Angelo and reported that the men and officers of Troop A were missing and presumed dead from thirst. The “Staked Plains Horror,” as the Galveston Daily News called it, quickly captured national attention. Although most of the soldiers eventually straggled back into camp, four had died, and others eventually faced court-martial for desertion. The buffalo hunters had ridden off on their own to find water, and the surviving soldiers had lived by drinking the blood of their dead horses and their own urine. A routine army scout had turned into disaster of the worst kind.

Although the failed expedition was widely reported at the time, its sparse treatments since then have relied exclusively on the white officers’ accounts. Paul Carlson has mined the courts-martial records for testimony of the enlisted men, memories of a white boy who rode with the Indians, and other buried sources to provide the first multifaceted narrative ever published. His gripping account provides not only a fuller version of what happened over those grim eighty-six hours but also a nuanced view of the interaction of soldiers, hunters, settlers, and Indians on the Staked Plains at this poignant moment before the final settling of the Comanches on their reservation in Indian Territory.

This Week in Texas Black History

Oct 28

English and Speech Professor Melvin Tolson organized the Forensic Society of Wiley College on this day in 1924. The debate teams compiled a ten-year winning streak. Tolson wrote the team’s speeches and the debaters memorized them with Tolson training them on every gesture and pause. He anticipated opponents’ arguments and wrote rebuttals before the actual debates. The 1935 team won the national championship, defeating the University of Southern California. The story of that team and Tolson’s leadership were the subjects of the 2007 film “The Great Debaters.”

Oct 29

E.H. Anderson, Prairie View State Normal School principal, died on this day in 1885. Anderson, a native of Memphis, had become the school’s second principal in 1879.

E.H. Anderson, Prairie View State Normal School principal, died on this day in 1885. Anderson, a native of Memphis, had become the school’s second principal in 1879.

Oct 30

On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy – leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy – leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

Oct 30

On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

Oct 31

On this day in 1835 a volunteer company was formed in Huntsville, Ala. to travel to Texas and help fight in the Texas Revolution against Mexico. A free black, Peter Allen, a flutist, was welcomed into the company as a musician. Allen, a native of Philadelphia, Pa. was the son of Richard Allen, founder and first Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. On March 20, 1836, Allen and his company, approximately 300 men commanded by Col. James Walker Fannin, participated in the Battle of Coleto Creek, but the men were forced to surrender and were imprisoned at Goliad. A week later, on Palm Sunday, all of the men were executed and their bodies burned in what became known as the Goliad Massacre. Asked by the Mexican commander to play a tune in exchange for his freedom, Allen refused and was also executed. Reportedly, Allen had responded to the request by saying, “No, I’ll not play, but I’ll just go along with the rest of the boys.”

Oct 31

State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

Oct 31

Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

Nov. 1

In 1903, on this day, Houston music impresario Don Robey was born. Robey was influential in developing the Texas blues scene, but he also produced major gospel talents. Robey’s music business empire included several music labels, most prominent being Peacock Records, and his was likely the first such enterprise run by an African-American. Robey produced dozens of blues and gospel artists, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Mighty Clouds of Joy.

Nov. 2

On this day in 1963, the Baylor University Board of Trustees voted to integrate the school, the world’s largest Baptist institution of higher learning. Hilton E. Howell, chairman of the board, said, “The action of the Baylor University Board of Trustees was taken after full and free discussion. While the final vote of the board adopting the new policy was not unanimous, the decision was reached by amicable discussion and democratic procedure.”

Nov. 2

On this day in 1999, legendary Prairie View A&M football coach Billy Nicks passed away in Houston at age 94. Nicks was a native of Griffin, Ga. and attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. As a coach, his 1941 Morris Brown team was named black college national champion, but it would be in Texas, at Prairie View, where Nicks would make his mark as one of the top coaches in college football history. He began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC opponent, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. Nicks’ overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. He is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

Nov. 3

Matthew “Bones” Hooks was born on this day in 1867 to former slave parents in Robertson County, Texas. Hooks was a cowboy and legendary horse breaker, who was also one of the first black cowboys to work alongside whites as a ranch hand. He later became a civic leader and worked with youth groups in Amarillo.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

The team

We live in an amazing world. There’s little chance my great grandfather, Big Pappa, could have ever envisioned world-wide communications at the click of a mouse. I’d like to say Big Pappa was a simple man. A country preacher from Gonzales, Texas. But he was so much more. He always told me that my brains…(more)

History and Honesty

Recently I was asked to review a new history textbook. While the prose was pretty good and the facts were basically the facts, the information surrounding the presidency of Barack Obama gave me pause. History will forever remember the initial response of the Republican brain trust immediately after Obama was acknowledged as the 44th president. (more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.