Can the national lynching memorial help Houston face its past?

Photo: More than 800 steel monuments represent victims of lynching at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in downtown Montgomery, Ala. (Credit: Johnathon Kelso, STR/NYT)

(Houston Chronicle) Houston is a city that is fiercely proud of its possibility. We tout our Medical Center, on the forefront of advances in cancer research. The Kinder Institute touts census numbers that show us as the most diverse region in the country. We are proud of our resilience in the face of recessions and catastrophic storms. Our can-do attitude keeps us hurtling into the future, determined to be a city upon a hill.

But this forward gaze can keep us from adequately remembering our past, which though inspiring is also fraught with racial violence.

The (lynching) memorial in Alabama…includes duplicates of each of the steel columns, lined up along the path outside the pavilion like coffins. The (Equal Justice Initiative) has invited counties around the country to claim their monuments and give them permanent homes so that we might more honestly reflect our history. The monument installation is just one arm of their Community Remembrance Projects, an ongoing campaign to recognize the victims of racial terror lynchings that also includes collecting soil from lynching sites and erecting historical markers.

Though the Equal Justice Initiative will not begin distributing the memorial monuments until 2019, the preliminary work to erect a historical marker here in Harris County is well on its way. Debra Blacklock-Sloan, an African-American genealogist, historical researcher and member of the Harris County Historical Commission, has taken the lead on local efforts to commemorate the victims of racial terror lynching. She initiated the project to place the Harris County monument on behalf of the Willie Lee Gay Chapter of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society as well as the Friends of the African-American Library at the Gregory School. (more)

The Defiant Ones

As young girls, they fought the fierce battle to integrate America’s schools half a century ago

(Smithsonian.com) On the morning of September 3, 1963, Millicent Brown put on the pleated skirt, blouse and new shoes she had picked out for her first day of tenth grade. Her older sister had helped set her hair with Dippity-do the day before, and it emerged as a neat bob after they took out the rollers—one point of anxiety relieved, at least.

Teenagers have always agonized over first impressions, but for Brown there was much more at stake than vanity. As a successful plaintiff in a school desegregation lawsuit, she would be one of two African-American students to attend formerly all-white Rivers High School in Charleston, South Carolina. Their own community was counting on them, but white racists were praying for them to fail. The school received three bomb threats that first day. It never got easier.

“I’d walk down the hallway and the students would part like the Red Sea,” Brown remembers. “They would make noises, make monkey sounds, act like I was a leper.” Believing she had to “represent the race,” she didn’t return their taunts.

It was a pressure felt by all of the African-American children who volunteered—or were drafted—to be “firsts” in the years before and after the Supreme Court struck down school segregation with its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. (Millicent Brown, who shares a last name with the plaintiff, was not part of that case.) Not by coincidence, the vast majority of these pioneers were girls and young women, a phenomenon that Rachel Devlin documents in her groundbreaking new work of recovered history, A Girl Stands at the Door (Basic Books). (more)

Photos: In their 1947 desegregation case in Hearne, Texas, Doris Raye Jennings Brewer (left) and twin sister Doris Faye Jennings Alton (right) were represented by Thurgood Marshall, the future Supreme Court justice. Though the girls lost their suit, it helped lay the groundwork for arguing that separate schools were discriminatory. (Photos by Lola Flash)

University of Utah Debuts New Online Archive on the History of Blacks in the Mormon Church

Paul Reeve, a professor of history at the University of Utah, has developed a new website that details the history of African Americans members of the Church of Latter-day Saints. The digital history database – Century of Black Mormons – documents Black participation in the church between 1830 and 1930.

Other than two early Black members of the priesthood, African Americans were prohibited from becoming members of the lay priesthood in the church until 1978. This excluded African Americans from leadership roles in the church and prevented them from performing many of the churches rituals.

But there were Black Mormons from the early days of the church. The first documented Black person to join the church was Black Pete, a former slave who was baptized in 1830, when the church was less than a year old. Researchers have identified about 200 African American members of the church during the nineteenth century. Some were slaves.

Professor Reeve stated that “visitors to the database will be surprised at the previously unknown stories they find as well as the diversity of geographic locations where Black Saints converted. I hope the information in the database will help scholars of religion and lay people alike begin to understand what it meant to be twice marginalized — a member of a minority race within a suspect minority religion.”

Visit the website here.

TIPHC Bookshelf

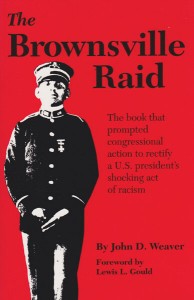

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Brownsville Raid,” by John D. Weaver.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Brownsville Raid,” by John D. Weaver.

Around midnight on August 13, 1906, shots rang out on the road between Brownsville, Texas, and Fort Brown, the old army garrison. Ten minutes later a young civilian lay dead, and angry residents swarmed the streets, convinced their homes had been terrorized by newly arrived soldiers. Inside Fort Brown, the alarm was sounded. Soldiers leaped from their bunks and grabbed their rifles, thinking they were under attack by hostile townspeople. The soldiers were black; the civilians were white.

Still proclaiming their innocence, 167 black infantrymen of the segregated Twenty-fifth Infantry Regiment were summarily dismissed without honor (or a trial) by President Theodore Roosevelt.

The Brownsville Raid, first published in 1970, is John D. Weaver’s searching study of the flimsy evidence presented in a 1909-1910 court of inquiry. That court had upheld the president’s action and closed the case against the soldiers, not one of whom had ever been found guilty of wrongdoing. The case remained closed until 1971 when, after reading The Brownsville Raid, Congressman Augustus F. Hawkins of Los Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department rectify the injustice.

Amid a flurry of national publicity, honorable discharges were finally granted in 1972. All were posthumous except for that of Private Dorsie Willis, who received his in a moving ceremony on his eighty-seventh birthday.

This Week in Texas Black History

Aug 12

In 1862, Julius Rosenwald was born in Springfield, Ill. In 1917, as president of Sears and Roebuck, he established the Julius Rosenwald Fund to support educating black children. His belief was that America could not prosper “if any large segment of its people were left behind.” His fund paid for the construction of more than 5,000 “Rosenwald” schools in 15 southern states to educate blacks, including 464 schools in Texas that impacted 57,330 students.

Related: “The Long Black Line,” Rosenwald Schools in Texas.

Aug 14

Alta Vista Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youth” was established by the Fifteenth Legislature of Texas on this day in 1876. The school would become Prairie View A&M University, the first state supported College in Texas for African Americans. The Texas Constitution of 1876, in separate articles, established an “Agricultural and Mechanical College” and pledged that “Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored children, and impartial provisions shall be made for both.”

Aug 13-14

In 1906, at Fort Brown, in Brownsville, Texas, members of the all-black 25th Infantry regiment supposedly killed a bartender and wounded a policeman, both white, the night after a white woman had reportedly been attacked by black soldiers. The men of the 25th denied participating in any of the incidents. However, despite dubious testimony from Brownsville citizens, President Theodore Roosevelt presumed the mens’ guilt and issued the largest summary dismissal in U.S. Army history as three companies (167 men) were dishonorably discharged. However, in 1972, U.S. Congressman Augustus Hawkins (D-CA) successfully had the discharges reversed to “honorable.”

Aug 15

In 1945, Gene Upshaw was born in Robstown, Texas. Upshaw was an All-America lineman at Texas A&I University (now Texas A&M-Kingsville), from 1963-66. He was a first-round draft pick of the Oakland Raiders in 1967 and for his 15-year career played on two Super Bowl winning teams. After his playing career, he became executive director of the National Football League Players’ Association and, in 1987, was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Aug 16

Surgeon Lee Gresham Pinkston was born on this day in 1883 in Forest, Mississippi. He received his M.D. degree at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn. He moved to Terrell, Texas in 1910 to begin private practice and later opened a clinic and drugstore. In 1927, he opened the Pinkston Clinic Hospital, which was the only operating clinic serving the African American community. He was the first of five African American doctors on the staff of Dallas’ St. Paul Hospital, where he remained until his death in 1961. Pinkston High School in Dallas is named in his honor. In 1936, Pinkston helped found the Democratic Progressive Voters League, one of the oldest black political organizations in the state of Texas.

Aug 16

Austin’s historic Victory Grill was opened on this day in 1945 (Victory over Japan Day) by band manager Johnny Holmes in a converted ice house as a venue for African American servicemen on R&R as well as those returning from World War II. The restaurant and night club became known for its blues and jazz music as well as its food and drink and attracted multi-racial crowds. At its peak, in the 1950s, most of the popular national R&B and jazz acts performed at the Victory Grill as part of the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” including Ike & Tina Turner, James Brown, Etta James, Billie Holiday, Chuck Berry, and Janis Joplin.

Aug 18

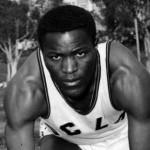

In 1935, Rafer Johnson was born in Hillsboro, Texas. Johnson was the gold medalist in the decathlon at the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. That same year, he received the James E. Sullivan Memorial Award as the nation’s outstanding amateur athlete. In 1984 he lit the torch signaling the opening of the Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Democratic Party – Fifty Years Later

In 1968, the Democratic Party met in Chicago to nominate its candidate for president. The Party was in chaos after the violent deaths of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. While King was not an acknowledged political figure, his non-violent social stance and his views on American involvement in Vietnam was influencing public policies. Perhaps more influential in the forthcoming implosion of the Democratic Party was the death of Robert Kennedy. His politics of

Television — Fifty Years Later

Social pundits often consider 1968 a pivotal year in our democracy. Fifty years later, the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy have many liberals questioning how compassionate our democracy may have been had they lived. There is no doubt they would have made a powerful one-two punch in eradicating many of the social ills caused by uncontrolled capitalism. Fifty years later we are also dealing with the implosion of the Democratic

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.