The Massacre of Black Sharecroppers That Led the Supreme Court to Curb the Racial Disparities of the Justice System

White Arkansans, fearful of what would happen if African-Americans organized, took violent action, but it was the victims who ended up standing trial

Photo: Elaine Defendants, Helena, Phillips County, Ark., ca. 1910, (Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library of Arkansas History and Art, Central Arkansas Library System)

(Smithsonian.com) The sharecroppers who gathered at a small church in Elaine, Arkansas, in the late hours of September 30, 1919, knew the risk they were taking. Upset about unfair low wages, they enlisted the help of a prominent white attorney from Little Rock, Ulysses Bratton, to come to Elaine to press for a fairer share in the profits of their labor. Each season, landowners came around demanding obscene percentages of the profits, without ever presenting the sharecroppers detailed accounting and trapping them with supposed debts.

“There was very little recourse for African-American tenant farmers against this exploitation; instead there was an unwritten law that no African-American could leave until his or her debt was paid off,” writes Megan Ming Francis in Civil Rights and the Making of the Modern American State. Organizers hoped Bratton’s presence would bring more pressure to bear through the courts. Aware of the dangers – the atmosphere was tense after racially motivated violence in the area – some of the farmers were armed with rifles.

At around 11 p.m. that night, a group of local white men, some of whom may have been affiliated with local law enforcement, fired shots into the church. The shots were returned, and in the chaos, one white man was killed. Word spread rapidly about the death. Rumors arose that the sharecroppers, who had formally joined a union known as the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) were leading an organized “insurrection” against the white residents of Phillips County.

Governor Charles Brough called for 500 soldiers from nearby Camp Pike to, as the Arkansas Democrat reported on Oct 2, “round up” the “heavily armed negroes.” The troops were “under order to shoot to kill any negro who refused to surrender immediately.” They went well beyond that, banding together with local vigilantes and killing at least 200 African-Americans (estimates run much higher but there was never a full accounting). (more)

Opinion: How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women

(Brent Staples, New York Times) The suffragist heroes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony seized control of the feminist narrative of the 19th century. Their influential history of the movement still governs popular understanding of the struggle for women’s rights and will no doubt serve as a touchstone for commemorations that will unfold across the United States around the centennial of the 19th Amendment in 2020.

That narrative, in the six-volume “History of Women’s Suffrage,” betrays more than a hint of vanity when it credits the Stanton-Anthony cohort with starting a movement that actually had diverse origins and many mothers. Its worst offenses may be that it rendered nearly invisible the black women who labored in the suffragist vineyard and that it looked away from the racism that tightened its grip on the fight for the women’s vote in the years after the Civil War.

Historians who are not inclined to hero worship — including Elsa Barkley Brown, Lori Ginzberg and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn — have recently provided an unsparing portrait of this once-neglected period. Stripped of her halo, Stanton, the campaign’s principal philosopher, is exposed as a classic liberal racist who embraced fairness in the abstract while publicly enunciating bigoted views of African-American men, whom she characterized as “Sambos” and incipient rapists in the period just after the war. The suffrage struggle itself took on a similar flavor, acquiescing to white supremacy — and selling out the interests of African-American women — when it became politically expedient to do so. This betrayal of trust opened a rift between black and white feminists that persists to this day. (more)

Activist’s archives of convict-leasing system reside at Rice

Growing collection illuminates the recent discovery of mass prisoner graves in Fort Bend County

“Prisoners working construction, Convict Leasing Photograph 8,” (Woodson Research Center – Fondren Library – Rice University)

(Rice University News & Media) What is convict leasing? Why do we know so little about it?

The answers to these questions can be found in the Woodson Research Center at Fondren Library. The Reginald Moore Sugar Land Convict-Leasing System Research Collection, established following the donation of archival materials by local activist Reginald Moore, has been housed at the Woodson Center since 2015.

In Texas, Moore is known for his insistence on finding and preserving physical proof of the system that routinely leased out prisoners to local plantations and other private landowners such as the Imperial Sugar Company, where they were worked under horrendous conditions, sometimes to death. After slavery ended, forced labor was still legal — if the person had been convicted of some offense. Trumped-up charges fed especially African Americans into the post-Civil War prison system where they could then be leased out as convict labor. Convict leasing was legalized slavery in a post-Civil War nation. (more)

Historic photos celebrate pioneering black explorer

Largely ignored for nearly a century, Matthew Henson made big contributions to polar exploration.

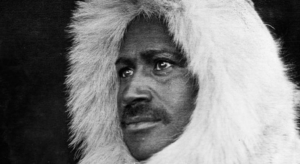

Although historians haven’t been able to confirm the fact, Henson said, “I think I’m the first man to sit on top of the world.” This photo was made on Canada’s Ellesmere Island in 1908. (PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT E. PEARY, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC)

(National Geographic) One of the pioneering polar explorers from the Golden Age of Exploration grew up as a poor orphan in Baltimore, and his achievements later in life were largely ignored because of his race.

Matthew Henson was one of the era’s few African-American explorers, and he may have been the first man, black or white, to reach the North Pole. His grueling adventures alongside U.S. Navy engineer Robert E. Peary are chronicled in these dramatic early photos.

Henson was born in 1866, on August 8. At age 13, as an orphan, he became a cabin boy on a ship, where the vessel’s captain taught him to read and write. Henson was working as a store clerk in Washington, D.C. in 1887 when he met Peary. Peary hired him as a valet, and the two began a long working relationship that spanned half a dozen epic voyages over two decades. (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

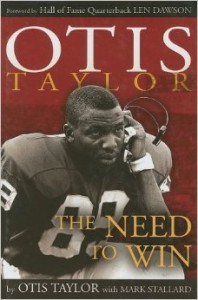

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Otis Taylor, The Need to Win,” by Otis Taylor, with Mark Stallard.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Otis Taylor, The Need to Win,” by Otis Taylor, with Mark Stallard.

“I wasn’t a football player for the fame or the Super Bowls; I was a football player for my own heart.” — Otis Taylor. He was one of pro football’s first modern receivers, possessing an overpowering combination of size, strength and speed. Otis Taylor moved on the field with gazelle-like ease; his soft hands and intimidating presence were a big part of the Kansas City Chiefs for 11 seasons and a major part of their win over the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl IV.

Starting from the projects of Houston, Taylor first starred for Prairie View A&M’s Panthers before bursting onto the American Football League scene with the Chiefs in 1965. By the early 1970s, he was widely considered one of the game’s finest receivers. The Need to Win is Taylor’s story — an insider’s look at the AFL and NFL player wars, the Super Bowl, racism in sports and America, how the game has changed and his place in football history.

This Week in Texas Black History

Aug 5

On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

Aug 6

President Lyndon Johnson, on this day signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African American and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests, but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

President Lyndon Johnson, on this day signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African American and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests, but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

Aug 9

Al Freeman, actor, died on this day in 2012 at age 78 in Washington, D.C. A San Antonio native, Freeman starred on Broadway in the 1960s in productions such as “Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright” and in plays by James Baldwin and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), including “Blues for Mister Charlie.” In 1979, Freeman became the first African American to receive a Daytime Emmy for a soap opera for his role as a police captain on “One Life to Live.” He also drew critical acclaim for his portrayal of Malcolm X in the mini-series “Roots: The Next Generations,” and in 1991 played Elijah Muhammad in the Spike Lee movie “Malcolm X.”

Al Freeman, actor, died on this day in 2012 at age 78 in Washington, D.C. A San Antonio native, Freeman starred on Broadway in the 1960s in productions such as “Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright” and in plays by James Baldwin and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), including “Blues for Mister Charlie.” In 1979, Freeman became the first African American to receive a Daytime Emmy for a soap opera for his role as a police captain on “One Life to Live.” He also drew critical acclaim for his portrayal of Malcolm X in the mini-series “Roots: The Next Generations,” and in 1991 played Elijah Muhammad in the Spike Lee movie “Malcolm X.”

Aug 9

This day marks the death, in 1912, of George Smith, founder and first principal of the first school for African Americans in Brownwood. Smith was a teacher, former Buffalo Soldier (10th Cavalry), and an elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He had been born into slavery in Virgina in 1847. After his military service ended at Fort Concho in San Angelo, he was recruited by AME Bishop Richad H. Cain to organize AME churches in communities where there were none. Smith traveled 100 miles northeast to Brownwood, where he found one AME church, but no school for black children. He organized and taught classes at various locations in the town, including the AME church. Five years after Smith’s death, a four-room stone facility was built for the school and, in 1934, was named in honor of former principal Rufus F. Hardin.

This day marks the death, in 1912, of George Smith, founder and first principal of the first school for African Americans in Brownwood. Smith was a teacher, former Buffalo Soldier (10th Cavalry), and an elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He had been born into slavery in Virgina in 1847. After his military service ended at Fort Concho in San Angelo, he was recruited by AME Bishop Richad H. Cain to organize AME churches in communities where there were none. Smith traveled 100 miles northeast to Brownwood, where he found one AME church, but no school for black children. He organized and taught classes at various locations in the town, including the AME church. Five years after Smith’s death, a four-room stone facility was built for the school and, in 1934, was named in honor of former principal Rufus F. Hardin.

Aug 10

On this day in 1918, jazz saxophonist Arnett Cobb was born in Houston. He was exposed to music at an early age; his grandmother taught him to play the piano when he was about 10 years old. He soon picked up the violin. As the only violin in an 80-piece brass band at Phillis Wheatley High School, he switched to saxophone in order to be heard. Known as the “Wild Man of the Tenor Sax,” Cobb made his professional debut with Frank Davis in 1933. Cobb played with Chester Boone from 1934-1936 and with Milt Larkin from 1936-1942. In 1942, he replaced Illinois Jacquet in Lionel Hampton‘s band, where he remained until 1947 when he left to form his own band. Serious injuries resulting from being hit by a car when he was 10 and an automobile accident in 1951 plagued him throughout his career, but never prevented Cobb from helping to shape and define what become known as the Texas-tenor sound.

On this day in 1918, jazz saxophonist Arnett Cobb was born in Houston. He was exposed to music at an early age; his grandmother taught him to play the piano when he was about 10 years old. He soon picked up the violin. As the only violin in an 80-piece brass band at Phillis Wheatley High School, he switched to saxophone in order to be heard. Known as the “Wild Man of the Tenor Sax,” Cobb made his professional debut with Frank Davis in 1933. Cobb played with Chester Boone from 1934-1936 and with Milt Larkin from 1936-1942. In 1942, he replaced Illinois Jacquet in Lionel Hampton‘s band, where he remained until 1947 when he left to form his own band. Serious injuries resulting from being hit by a car when he was 10 and an automobile accident in 1951 plagued him throughout his career, but never prevented Cobb from helping to shape and define what become known as the Texas-tenor sound.

Aug 11

On this date in 1922, Negro Leagues star and Tuskegee Airman John “Mule” Miles was born in San Antonio. Miles attended Phillis Wheatley High School, then served as a mechanic for the 99th Pursuit Squadron. After that, Miles played for the Chicago American Giants from 1946 to 1949 and in 1947 hit 11 home runs in 11 straight games, a feat that has never been equaled. He played alongside such greats as Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks and Satchel Paige. Giants’ manager Candy Jim Taylor, gave Miles his nickname saying that he “hit like a mule kicks.” Among his many honors, Miles was inducted into the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame in 2000, to the San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame in 2003, to the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame in 2009, and to the Prairie View Interscholastic League Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2010.

On this date in 1922, Negro Leagues star and Tuskegee Airman John “Mule” Miles was born in San Antonio. Miles attended Phillis Wheatley High School, then served as a mechanic for the 99th Pursuit Squadron. After that, Miles played for the Chicago American Giants from 1946 to 1949 and in 1947 hit 11 home runs in 11 straight games, a feat that has never been equaled. He played alongside such greats as Jackie Robinson, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks and Satchel Paige. Giants’ manager Candy Jim Taylor, gave Miles his nickname saying that he “hit like a mule kicks.” Among his many honors, Miles was inducted into the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame in 2000, to the San Antonio Sports Hall of Fame in 2003, to the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame in 2009, and to the Prairie View Interscholastic League Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2010.

Aug 11

Kansas City Chiefs wide receiver Otis Taylor was born on this day in 1942 in Houston. Taylor attended E.E. Worthing HS where he starred in football and basketball. At Prairie View A&M, Taylor was a member of the Panthers’ 1963 and 1964 Black College National Championship teams. He was a fourth round draft pick of the Chiefs where Taylor would spend his entire AFL/NFL career (1965-1974). He remains the Chiefs second-leading receiver in career touchdowns (57) and is No. 4 on their list for all-time receiving yards (7,306). He scored a dynamic catch-and-run touchdown in Kansas City’s 23-7 upset win over the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl IV. Taylor was twice named an All-Pro.

Kansas City Chiefs wide receiver Otis Taylor was born on this day in 1942 in Houston. Taylor attended E.E. Worthing HS where he starred in football and basketball. At Prairie View A&M, Taylor was a member of the Panthers’ 1963 and 1964 Black College National Championship teams. He was a fourth round draft pick of the Chiefs where Taylor would spend his entire AFL/NFL career (1965-1974). He remains the Chiefs second-leading receiver in career touchdowns (57) and is No. 4 on their list for all-time receiving yards (7,306). He scored a dynamic catch-and-run touchdown in Kansas City’s 23-7 upset win over the Minnesota Vikings in Super Bowl IV. Taylor was twice named an All-Pro.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Democratic Party – Fifty Years Later

In 1968, the Democratic Party met in Chicago to nominate its candidate for president. The Party was in chaos after the violent deaths of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. While King was not an acknowledged political figure, his non-violent social stance and his views on American involvement in Vietnam was influencing public policies. Perhaps more influential in the forthcoming implosion of the Democratic Party was the death of Robert Kennedy. His politics of

Television — Fifty Years Later

Social pundits often consider 1968 a pivotal year in our democracy. Fifty years later, the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy have many liberals questioning how compassionate our democracy may have been had they lived. There is no doubt they would have made a powerful one-two punch in eradicating many of the social ills caused by uncontrolled capitalism. Fifty years later we are also dealing with the implosion of the Democratic

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.