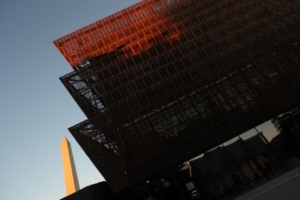

The Museum Grappling With the Future of Black America

The Smithsonian’s memorial of African American history and culture turns 1 at a time when its lessons are particularly resonant.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC)

“It is an act of patriotism to understand where we’ve been.”

So said President Barack Obama during his speech at the opening ceremony of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), which celebrated its one-year anniversary on September 24. “This,” Obama had continued, “is the place to understand how protest and love of country don’t merely coexist, but inform each other.” His words feel eerily prescient given the national news of the past week – a week that coincidentally marked the 60th anniversary of the Little Rock Nine’s first day at an all-white high school – and, more broadly, the past year.

Since the election of Donald Trump, conversations about the history of race and the utility of protest have remained at the forefront of political debate. It would seem that dissent and love of country are incompatible to Trump, contrary to Obama’s words. At the same time, Trump’s definition of patriotism isn’t informed by the understanding that to be black in America is to have hope for the future despite generations of disenfranchisement and racist terror.

It’s within this fraught political context that the most comprehensive exhibit of black history in America has operated for the better part of a year, almost serendipitously overlapping with the rise of the current administration. The NMAAHC has attracted more than 2.5 million people thus far and averages about 8,000 visitors daily, including President Trump shortly after his inauguration. Even though the museum is rife with symbols of fortitude and freedom – and notably sits close to monuments dedicated to Presidents Jefferson and Washington, both of whom owned slaves – it isn’t wholly insulated from the increasingly conspicuous polarization taking place outside its walls. Events like the white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August make the museum’s director, Lonnie Bunch, think deeply about how history can help people have reasoned debates about issues like the country’s current racial tension. “This is a moment that is going to force America to recognize that it’s in a war for [its] soul,” Bunch told me. Shortly before the Charlottesville rally, which left one counter-protester dead, visitors found a noose hanging inside the museum. (more)

Before Trump vs. the NFL, there was Jackie Robinson vs. JFK

Jackie Robinson, left, in his playing days. He pressured President John F. Kennedy, right, on civil rights. (AP photos)

President Trump ignited a firestorm this weekend by demanding NFL owners fire players who kneel during the national anthem, setting off a wave of protests by players, coaches and even owners that riveted the country Sunday. But long before Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players drew Trump’s ire, professional athletes protested racial oppression in the United States. One African American sports icon even badgered a president publicly. Jackie Robinson, the hero who integrated Major League Baseball in 1947, spoke out loudly for civil rights and challenged President John F. Kennedy to stop dithering on black equality.

Unlike Trump, JFK sought to understand Robinson’s complaints, corresponded by letter with the baseball star and met with him to hear his concerns. Eventually, in response to Robinson, Martin Luther King Jr. and a growing protest movement, Kennedy delivered a landmark speech in 1963 that spoke of inequality in moral terms and set in motion civil rights legislation that passed the year after his assassination. For his part, Jackie Robinson, after having repeatedly disparaged Kennedy, arrived at a new appreciation for JFK’s willingness to hear the pleas of African Americans and lead on civil rights.

Related: Here’s what Jackie Robinson had to say about the national anthem

For a lot of people, athletes expressing their political viewpoints by protesting the national anthem is a relatively new concept. But the more things change, the more they stay the same. Jackie Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, but he was an activist well beyond that momentous occasion, highlighting issues black athletes face as editor for Our Sports magazine. Robinson had an issue with the national anthem as well. (more)

Cherokee County History Spotlight: Robert Tilley/James Scott-Larissa (African-Americans)

(Jacksonville Progress) Among the pioneers of the Larissa community were those widely known for their loyalty to the church and their love of education. Among those pioneers were the McKees, Newtons, Ewings, Erwins, Bones, Campbells, Yoakums, and Longs. James Scott, a member of the Larissa C.M.E. Church states that African American leaders such as Henry Tilley, Albert Roach, Wallace Roach, J.W. Roach, Curtis Sanders, Ellis Campbell, Clarence Harris, Earnest Smith and Frank Smith played a significant role in the continued development of Larissa.

(Jacksonville Progress) Among the pioneers of the Larissa community were those widely known for their loyalty to the church and their love of education. Among those pioneers were the McKees, Newtons, Ewings, Erwins, Bones, Campbells, Yoakums, and Longs. James Scott, a member of the Larissa C.M.E. Church states that African American leaders such as Henry Tilley, Albert Roach, Wallace Roach, J.W. Roach, Curtis Sanders, Ellis Campbell, Clarence Harris, Earnest Smith and Frank Smith played a significant role in the continued development of Larissa.

Around 1885 there was a little log church erected in the Larissa community known as Larissa C.M.E. church. The church was not well constructed and was repaired later. The Rev. L. Callaway was the Pastor of the 1885 church. Some of the other Pastors were Rev. Morehead, Rev. Hollis-Worth, Rev. I.M. Bell, Rev. George Smith, Rev. H.P. Peterson, Rev. H. Heft, Rev. W.M. Nelson, Rev. Wesley, Rev. Jim Collens and Rev. E.G. Ragsdale.

Larissa consists of three cemeteries, Old Baptist Larissa, Old Larissa and The Larissa. This documents the fact that the Larissa Community was originally one community. The establishment of railroads through Jacksonville and Mt. Selman started the decline of the Larissa Community. By 1910 this resulted in the development of a predominately African American community for Larissa. (more)

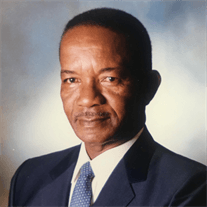

Obit: First African-American student to earn doctorate from Texas A&M dies at 91

James E. Johnson

(KXXV, College Station) Becoming the first African-American to earn a doctorate from Texas A&M University was no easy task for James E. Johnson.

In fact, he says he was turned away numerous times because of segregation. Johnson died at the age of 91 on Oct. 6, according to his family.

He grew up and attended school in Rockdale and was accepted into Prairie View A&M in 1944, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in education. During that time, he was drafted into the Armed Forces and performed police duties in the Army until he was honorably discharged in 1948. He returned to Prairie View in 1948 after his discharge and finished his bachelor’s degree. (more)

Black history in brief

October 23, 1945: Jackie Robinson and pitcher John Wright were signed by Branch Rickey, president of the Brooklyn Dodgers Baseball Club, to play on a Dodger farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League. Robinson went on to become the first African-American baseball player to play on a major league team.

October 24, 1935: Langston Hughes’ first play, Mulatto, opened on Broadway. It was the longest-running play (373 performances) by an African-American writer until Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun premiered in 1959.

Benjamin O. Davis Sr.

October 25, 1940: Benjamin O. Davis Sr. became the first African American promoted to Brigadier General in the U.S. Army. He later served with the European Theater of Operation. President Harry S. Truman presided at his retirement ceremony after 50 years of service. Davis died in 1970.

October 26, 1911: Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson was born in New Orleans. After moving to Chicago, she became one of the first singers to move gospel music from the church to the mainstream, attracting white audiences and selling millions. She became a voice, too, for the civil rights movement. She sang at the 1963 March on Washington, the 1965 Selma march and at many rallies for Martin Luther King Jr. “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” was King’s favorite, and she sang it at his funeral. When she died four years later, Aretha Franklin sang the song at her funeral. In 1997, Jackson was inducted posthumously into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

October 27, 1954: Following in his father’s military footsteps, Benjamin O. Davis Jr. became the first African-American general in the U.S. Air Force. In 1943, he organized and commanded the unit of all African-American pilots, the Tuskegee Airmen, flying 60 combat missions, receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for his service. Five years later, he helped plan the desegregation of the Air Force. During the Korean War, he commanded a fighter wing. In 1998, President Bill Clinton promoted him to full general in honor of his service. He died in 2002.

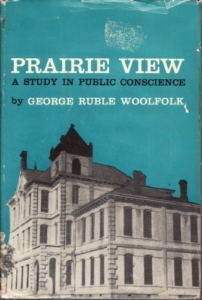

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. In recognition of Prairie View’s homecoming week, we offer, “Prairie View: A Study in Public Conscience, 1878-1946,” by George Ruble Woolfolk.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. In recognition of Prairie View’s homecoming week, we offer, “Prairie View: A Study in Public Conscience, 1878-1946,” by George Ruble Woolfolk.

This digitized edition presents the quintessential history of the university’s founding and early years written by the distinguished former Prairie View professor. Woolfolk, a preeminent historian (southern history and African-American studies) and scholar, served at PVAMU for five decades, beginning in 1943 during which time he was chair of the history department, chair of the Division of Social Science, and was listed in Who’s Who in America and noted as one of the Outstanding Educators of America.

In the book, Woolfolk shows the “impetus for public education in Texas from the state’s founding to the Civil War and the introduction of public education for its Negro citizens as a result of the war and reconstruction.”

He writes, in the preface, “This is a study of the development of higher education for the Negro in Texas under the ideology of the land-grant pattern. Conceived as a part of the revolution implicit in the rise of industrialism to prestige and power in the nation with the coming of the Republican Party to control of the national government in 1860, Justin Morrill’s brain-child has meant many things to many people as it took shape in the nation, and especially in the post-bellum South. The elaboration and evolution of this pattern of education has never been definitely explained. This is particularly true in the case of the Negro’s adaptations, subject as they were to the many dynamic factors and forces attendant upon his adjustment to his status as a free man and the efforts to integrate him into the broad pattern of democracy which the creation of these schools was designed to foster.”

This Week in Texas Black History, Oct. 22-28

Christia Daniels Adair

22 – Christia Daniels Adair, suffragist and civil rights activist, was born on this day in 1893, in Victoria, Texas. A graduate of Prairie View Normal College, Adair was an elementary school teacher in Kingsville where she organized a group of black and white women to acquire voting rights in 1919. She later became one of the first black women to vote in the state’s previously all-white primary. Adair and her husband relocated to Houston where she would become executive secretary for the Houston chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. With the NAACP she led campaigns to desegregate the city’s public schools, libraries, transportation, hospitals and other public facilities. In 1952, Adair help found the first Harris County interracial political group, the Harris County Democrats. In 1977, a Houston city park was named for her.

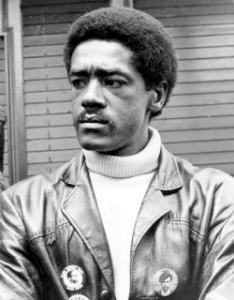

Bobby Seale

22 – In 1936, Bobby Seale was born on this day in Dallas. Seale would become a political activist and revolutionist, and in 1966 co-founded (with Huey Newton) and was national chairman of the Black Panther Party. J. Edgar Hoover, Federal Bureau of Investigation director, described the Panthers as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. “Seale was also one of the “Chicago Eight” defendants charged with conspiring to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic Party Convention. Seale was charged with 16 counts of contempt of court after repeated outbursts during the trial for which he was bound and gagged. He spent four years in prison. In 1973, he finished second in a run for mayor of Oakland, Ca. Since, Seale has been a community activist and author. Among his several books are his biography, “Seize the Time,” and a cook book, “Barbeque’n with Bobby.”

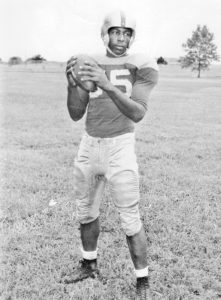

Charlie Brackins

23 – On this day in 1955, Dallas native Charlie “Choo-Choo” Brackins played the final minutes of a game against the Cleveland Browns, making him the fourth black quarterback to play in an NFL game, but the first quarterback from a historically black college to play in the league. Brackins attended Lincoln High School in Dallas then starred at Prairie View A&M, leading the Panthers to 33 wins in the 37 games he played. He was a 16th round pick by the Green Bay Packers in the 1955 draft.

24 – Two historically black Austin institutions of higher education, Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College, merged to form Huston-Tillotson College (now University) on this day in 1952. Tillotson Collegiate and Normal Institute (named after Unitarian minister George Jeffrey Tillotson) first opened its doors in 1881, and Samuel Huston College in 1876 in Dallas, relocating to Austin two years later. The two East Austin schools were less than a mile apart. Huston-Tillotson is a coeducational college of liberal arts and sciences, operated jointly under the auspices of the American Missionary Association of the United Church of Christ and the Board of Education of the United Methodist Church.

24 – Two historically black Austin institutions of higher education, Samuel Huston College and Tillotson College, merged to form Huston-Tillotson College (now University) on this day in 1952. Tillotson Collegiate and Normal Institute (named after Unitarian minister George Jeffrey Tillotson) first opened its doors in 1881, and Samuel Huston College in 1876 in Dallas, relocating to Austin two years later. The two East Austin schools were less than a mile apart. Huston-Tillotson is a coeducational college of liberal arts and sciences, operated jointly under the auspices of the American Missionary Association of the United Church of Christ and the Board of Education of the United Methodist Church.

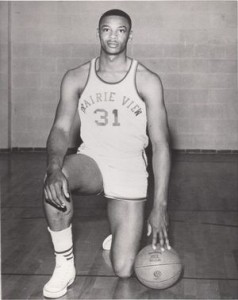

Zelmo Beaty

25 – Prairie View and National Basketball Association great Zelmo Beaty was born on this day in 1939 in Hillister (50 miles north of Beaumont). Beaty played during segregation at all-black Scott High School in nearby Woodville. At PV, Beaty led the Panthers to the 1962 NAIA national championship and was named tournament MVP. He averaged 25 points and 20 rebounds during his collegiate career. Though undersized at 6-9 for a center, Beaty was the third overall pick in the 1962 NBA draft by the St. Louis Hawks (now Atlanta), made the 1962-63 NBA All-Rookie Team and was a league All-Star in 1966 and 1968 in an era dominated by centers Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell. Beaty jumped to the American Basketball Association and led the Utah Stars to their only championship in 1971. In eight NBA seasons, he averaged 16 points and 11 rebounds a game. He is a member of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame.

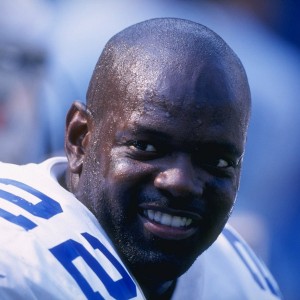

Emmitt Smith

27 – On this day in 2002, Dallas Cowboys’ running back Emmitt Smith passed Chicago Bears great Walter Payton and became the National Football League’s all-time rushing leader on an 11-yard gain in the fourth quarter of the Cowboys’ 17-14 loss to the Seattle Seahawks in Dallas. Smith retired two years later with 18,355 career yards to Payton’s 16,726. Smith, who played collegiately at the University of Florida, was the Cowboys first round pick (number 17 overall) in the NFL’s 1990 draft. He played in eight Pro Bowls and was a four-time first-team All-Pro. In 2005, Smith was inducted to the Cowboys’ Ring of Honor and in 2010 he was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Melvin Tolson

28 – English and Speech Professor Melvin Tolson organized the Forensic Society of Wiley College on this day in 1924. The debate teams compiled a ten-year winning streak. Tolson wrote the team’s speeches and the debaters memorized them with Tolson training them on every gesture and pause. He anticipated opponents’ arguments and wrote rebuttals before the actual debates. The 1935 team won the national championship, defeating the University of Southern California. The story of that team and Tolson’s leadership were the subjects of the 2007 film “The Great Debaters.”

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Latest Entries

A New Hope

Forgive me for borrowing the title of one of the most profitable films in history, “Star Wars: A New Hope.” I’ve always been enamored by space. I’m a child of the 1960s and I remember playing with my Major Matt Mason action figure (not a doll!) as my family [...]

Tell me the truth

Democracy – a) government by the people, b) a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them, directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections. Merriam-Webster Dictionary There were many things I learned from my father. [...]

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.