African Americans Have Lost Untold Acres of Land Over the Last Century

An obscure legal loophole is often to blame

In the 45 years following the Civil War, freed slaves and their descendants accumulated roughly 15 million acres of land across the United States, most of it in the South. Land ownership meant stability and opportunity for black families, a shot at upward mobility and economic security for future generations. The hard-won property was generally used for farming, the primary occupation of most Southern blacks in the early 20th century. By 1920, there were 925,000 black-owned farms, representing about 14 percent of all farms in the United States.

Over the course of the 20th century, however, that number dropped precipitously. Millions of farmers of all races were pushed off their land in the early part of the century, including around 600,000 black farmers. By 1975, just 45,000 black-owned farms remained. “It was almost as if the earth was opening up and swallowing black farmers,” writes scholar Pete Daniel in his book Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights. Implicit in the decline of black farming was the loss of the land those farmers once tilled. Today, African Americans compose less than 2 percent of the nation’s farmers and 1 percent of its rural landowners.

Many factors contributed to the loss of black-owned land during the 20th century, including systemic discrimination in lending by the US Department of Agriculture, the industrialization that lured workers into factories, and the Great Migration. But the lesser-known issue of heirs’ property also played a role, allowing untold thousands of acres to be forcibly bought out from under black rural families—often second-, third-, or fourth-generation landowners whose ancestors were enslaved—by real-estate developers and speculators. (more)

Photo: Queen Quet, Head-of-State and Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation, which once occupied Hilton Head and most of the coastal islands that fringe the southeastern United States. (Richard Ellis)

Literary: Americans were becoming fascinated with black Gullah culture, just as President Coolidge visited

The culture on Sapelo Island, Georgia was unique

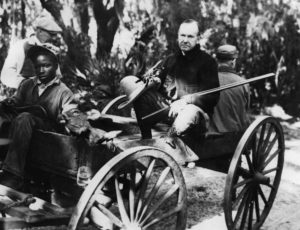

President Calvin Coolidge (with shotgun) returning from a hunting trip on Sapelo Island, Georgia, with his host Howard Coffin in 1925. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In the 1920s and 1930s, researchers descended on Sapelo Island, Georgia, seeking to draw connections between the island’s African-American residents and their African heritage. In her new book, Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination (University of North Carolina Press), Melissa L. Cooper examines the unique history of Low Country blacks, and explores the motivations of the anthropologists and folklorists who sought to tell particular stories about them.

Four days after Christmas in 1928, dozens of Sapelo Islanders gathered around an oxcart on a dirt road that snaked through live oaks covered in Spanish moss and waited for the white man who was filming them to tell them what to do next. They had already sung “Old Time Religion,” “Steal Away to Jesus,” and performed a rendition of the minstrel tune that was named the Kentucky state song that year — “My Old Kentucky Home.” Each time the camera rolled, the filmmaker directed the Islanders to sing while riding in, or walking alongside, the ox cart. The solemn choral group likely included some of the men Howard Coffin hired to build roads, prepare crops, man his sawmill, tend his cattle, work in his greenhouse, or build boats and other structures. Likewise, several of the women in the chorus were either paid by Coffin to work in his shrimp and oyster cannery or in his fields, or were members of the domestic staff who cooked his meals and cleaned his mansion. Even though the filmmaker captured several “takes” designed to look like mundane and typical Sapelo scenes, that day was anything but ordinary. That day, Sapelo Islanders found themselves in front of cameras, recording equipment, and in the presence of a small crowd of newspaper reporters because their boss had recruited them to entertain the most powerful white man in America, President Calvin Coolidge. (more)

Double Bayou, TX: Lee College alum’s research leads to marker

Before he began researching the Double Bayou Dance Hall in Chambers County to complete his thesis for the American Studies course offered through the Lee College Honors Program, alumnus Caleb Moore had never heard of the little one-room gathering spot on the “Chitlin’ Circuit” where blues legends like T-Bone Walker and Big Joe Turner stopped to perform on their way to Houston.

Before he began researching the Double Bayou Dance Hall in Chambers County to complete his thesis for the American Studies course offered through the Lee College Honors Program, alumnus Caleb Moore had never heard of the little one-room gathering spot on the “Chitlin’ Circuit” where blues legends like T-Bone Walker and Big Joe Turner stopped to perform on their way to Houston.

Now, many of the facts that Moore uncovered for his research paper grace a Texas Historical Marker recognizing the dance hall’s significance to the predominately African-American community of Double Bayou and those who flocked to it for generations, eager to end a hard day’s work by dancing to the rich sounds of Texas blues filling the rafters and spilling into the surrounding woods. (more)

50 years after the uprising

Five Days of Unrest That Shaped, and Haunted, Newark

The fuse that ignited this city — violent clashes with the police, gunfire, flames from burning buildings — was a rumor. Word spread that a black cabdriver had been killed inside a police precinct house. It was not true — the driver had been arrested and injured.

The fuse that ignited this city — violent clashes with the police, gunfire, flames from burning buildings — was a rumor. Word spread that a black cabdriver had been killed inside a police precinct house. It was not true — the driver had been arrested and injured.

Still, it was enough to inflame a population filled with years of pent-up grievances: not only abuse at the hands of the police, but entrenched, unaddressed poverty, urban renewal policies that bypassed black residents and a white political power structure that had long ignored their needs.

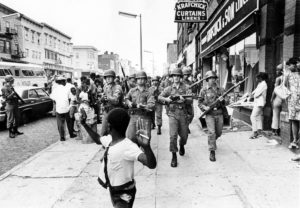

The unrest, which started on the night of July 12, 1967, and ended on July 17, came during a period when racial tensions were exploding into violent conflagrations across the country: the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles, Harlem, Detroit and nearby New Jersey communities, including Plainfield.

Amid all that, what made Newark’s unrest striking was the physical toll, placing it among the deadliest of the riots. Over several days, 26 people were killed — many of them black residents, as well as a white firefighter and a white police detective — and more than 700 were injured. The riots caused about $10 million in damages and reduced entire blocks to charred ruins, some of which remain vacant grass-covered lots. (more)

Photo: The National Guard on Springfield Avenue in Newark on July 14, 1967. Credit: Don Hogan Charles/The New York Times

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas,” edited by Bruce A. Glasrud.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas,” edited by Bruce A. Glasrud.

Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas provides an arresting look at the history of violence against African Americans in Texas. From a lynching in Paris at the turn of the century to the 1998 murder of Jasper resident James Byrd Jr., who was dragged to death behind a truck, this volume uncovers the violent side of race relations in the Lone Star State.

Historian Bruce A. Glasrud has curated an essential contribution to Texas history and historiography that will also bring attention to a chapter in the state’s history that, for many, is still very much a part of the present.

“Bruce A. Glasrud’s impressive collection of carefully researched essays is an important contribution in the field of racial violence. This timely collection also deepens our understanding of the modern civil rights movement and the resistance to a racially just society. The twelve contributors demonstrate, sadly, the persistence of racial violence across time and into the twenty-first century. Anti-Black Violence reveals a broad spectrum of white violence and numerous forms of racial control, and it illustrates, too, the creative range of responses that black Texans used to cope with white violence, ranging from organized activism and out-migration to racial accommodation. These powerful narratives reveal finally that the Lone Star State was every bit as brutal and vicious toward African Americans as Mississippi and Georgia in its quest to assert white supremacy and maintain a subservient and inferior status for African Americans.”—Albert S. Broussard, author of Expectations of Equality: A History of Black Westerners

This Week in Texas Black History, July 9-15

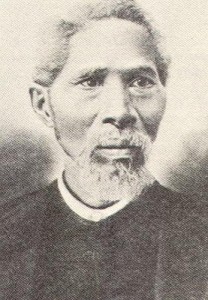

11 – On this day in 1828, Rev. John Henry “Jack” Yates was born into slavery in Gloucester County, Virginia. He moved with his wife (Harriet) and 11 children in 1863 when Harriet’s master relocated with his slaves to Matagorda County. Following emancipation in 1865, Yates moved his family to Houston where he began working with the Home Missionary Society and was ordained a Baptist minister. In 1866, after being ordained, Yates became the first pastor of Antioch Baptist Church, the first black Baptist church in Houston. Yates was also active in education, volunteering Antioch as the site for a Freedmen’s Bureau school and he also helped bring the first Baptist college to Texas, Bishop Academy, an institution that prepared students for employment in trades, business and ministry. Houston’s Jack Yates High School, built in 1926, is named in his honor.

11 – On this day in 1828, Rev. John Henry “Jack” Yates was born into slavery in Gloucester County, Virginia. He moved with his wife (Harriet) and 11 children in 1863 when Harriet’s master relocated with his slaves to Matagorda County. Following emancipation in 1865, Yates moved his family to Houston where he began working with the Home Missionary Society and was ordained a Baptist minister. In 1866, after being ordained, Yates became the first pastor of Antioch Baptist Church, the first black Baptist church in Houston. Yates was also active in education, volunteering Antioch as the site for a Freedmen’s Bureau school and he also helped bring the first Baptist college to Texas, Bishop Academy, an institution that prepared students for employment in trades, business and ministry. Houston’s Jack Yates High School, built in 1926, is named in his honor.

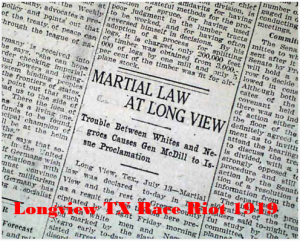

11-12 – On these days in 1919 the Longview Race Riot occurred, precipitated by an article in the July 10 issue of the Chicago Defender describing the death of a young black man, Lemuel Walters, in Longview. The article, written by Longview teacher Samuel L. Jones, reported that Walters and an unnamed white woman from Kilgore were in love and quoted her as saying they would have married if they had lived in the North. Walters, according to the article, was safely locked in the Gregg County Jail until the sheriff willingly handed him over to a white mob that murdered him on June 17. Jones was held responsible for the article, and on July 10 was accosted and beaten, supposedly by two brothers of the Kilgore woman. News of the article and of the attack on Jones inflamed tempers of both races, and on July 11, a group of twelve to fifteen angry white men drove to Jones’s house where they engaged in a gunfight with residents of the house. Some of the white men went to the fire station and rang the alarm to attract more recruits; others broke into a hardware store to get guns and ammunition. A white mob burned several black homes and a dance hall. Governor William P. Hobby sent Texas Rangers and National Guardsmen to Longview and placed the city and county under martial law. The rangers arrested seventeen white men on charges of attempted murder. Twenty-one black men were arrested, charged, and sent to Austin temporarily for their own safety. Nine white men were also charged with arson. None of the whites or blacks was ever tried. (For more, see, TIPHC Bookshelf for “Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas; see video)

11-12 – On these days in 1919 the Longview Race Riot occurred, precipitated by an article in the July 10 issue of the Chicago Defender describing the death of a young black man, Lemuel Walters, in Longview. The article, written by Longview teacher Samuel L. Jones, reported that Walters and an unnamed white woman from Kilgore were in love and quoted her as saying they would have married if they had lived in the North. Walters, according to the article, was safely locked in the Gregg County Jail until the sheriff willingly handed him over to a white mob that murdered him on June 17. Jones was held responsible for the article, and on July 10 was accosted and beaten, supposedly by two brothers of the Kilgore woman. News of the article and of the attack on Jones inflamed tempers of both races, and on July 11, a group of twelve to fifteen angry white men drove to Jones’s house where they engaged in a gunfight with residents of the house. Some of the white men went to the fire station and rang the alarm to attract more recruits; others broke into a hardware store to get guns and ammunition. A white mob burned several black homes and a dance hall. Governor William P. Hobby sent Texas Rangers and National Guardsmen to Longview and placed the city and county under martial law. The rangers arrested seventeen white men on charges of attempted murder. Twenty-one black men were arrested, charged, and sent to Austin temporarily for their own safety. Nine white men were also charged with arson. None of the whites or blacks was ever tried. (For more, see, TIPHC Bookshelf for “Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas; see video)

12 – Texas Congresswoman, Barbara Jordan, became the first African-American to give the keynote address at a major national political convention by giving a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention on this date in 1976 in New York City. In opening her remarks, Jordan noted the significance of her appearance: “…my presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American dream need not ever be deferred.” Jordan was a Houston native and graduate of Phillis Wheatley High School and Texas Southern University.

12 – Texas Congresswoman, Barbara Jordan, became the first African-American to give the keynote address at a major national political convention by giving a keynote address at the Democratic National Convention on this date in 1976 in New York City. In opening her remarks, Jordan noted the significance of her appearance: “…my presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American dream need not ever be deferred.” Jordan was a Houston native and graduate of Phillis Wheatley High School and Texas Southern University.

15 – Forest Whitaker, actor, producer, and director, was born on this day in 1961 in Longview. At age four, he moved with his family to Los Angeles. Whitaker was a star tackle at Palisades High School and received college football scholarship offers, however, after suffering a back injury he began to study opera and acting. In 1982, he made his film debut in the comedy Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but his breakout role came in 1988 portraying jazz legend Charlie Parker, in the Clint Eastwood film, Bird, for which Whitaker earned the Cannes Film Festival award for Best Actor and a Golden Globe nomination. His first directing effort was the film Waiting to Exhale in 1995, and in 2006 was widely lauded for his role as Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in the movie The Last King of Scotland. For that, Whitaker earned the 2007 Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, making him the fourth African-American actor to do so, joining Sidney Poitier, Denzel Washington, and Jamie Foxx. That same year, Whitaker played Dr. James Farmer Sr. in The Great Debaters, the movie about the acclaimed Wiley College debate team of the 1930s and its coach, Melvin Tolson.

15 – Forest Whitaker, actor, producer, and director, was born on this day in 1961 in Longview. At age four, he moved with his family to Los Angeles. Whitaker was a star tackle at Palisades High School and received college football scholarship offers, however, after suffering a back injury he began to study opera and acting. In 1982, he made his film debut in the comedy Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but his breakout role came in 1988 portraying jazz legend Charlie Parker, in the Clint Eastwood film, Bird, for which Whitaker earned the Cannes Film Festival award for Best Actor and a Golden Globe nomination. His first directing effort was the film Waiting to Exhale in 1995, and in 2006 was widely lauded for his role as Ugandan dictator Idi Amin in the movie The Last King of Scotland. For that, Whitaker earned the 2007 Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, making him the fourth African-American actor to do so, joining Sidney Poitier, Denzel Washington, and Jamie Foxx. That same year, Whitaker played Dr. James Farmer Sr. in The Great Debaters, the movie about the acclaimed Wiley College debate team of the 1930s and its coach, Melvin Tolson.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Big People, Big Moments,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.