The East St. Louis Race Riot Left Dozens Dead, Devastating a Community on the Rise

Three days of violence forced African-American families to run for their lives and the aftereffects are still felt in the Illinois city today

Photo: Two National Guardsmen escort an African-American man in the tense summer weeks of 1917 in East St. Louis, Illinois. (Bettmann)

(Smithsonian.com) “No one really knows about this. . . . I know about it because my father, uncles and aunts lived through it,” Dhati Kennedy says.

He’s referring to an incident that survivors call the East St. Louis Race War. From July 1 through July 3, 1917, a small Illinois city located across the river from its Missouri counterpart was overrun with violence. Kennedy’s father Samuel, who was born in 1910, lived in East St. Louis when the conflict occurred. A smoldering labor dispute turned deadly as rampaging whites began brutally beating and killing African-Americans. By the end of the three-day crisis, the official death toll was 39 black individuals and nine whites, but many believe that more than 100 African-Americans were killed.

“We spent a lifetime as children hearing these stories. It was clear to me my father was suffering from some form of what they call PTSD,” Kennedy recalls. “He witnessed horrible things: people’s houses being set ablaze, . . . people being shot when they tried to flee, some trying to swim to the other side of the Mississippi while being shot at by white mobs with rifles, others being dragged out of street cars and beaten and hanged from street lamps.” (Read more, also watch related videos)

Historians Uncover Slave Quarters of Sally Hemings at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

Descendants of Monticello’s enslaved families in the Kitchen Yard, above Mulberry Row in 2016 (Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello)

(NBC News) Archaeologists have excavated an area of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello mansion that has astounded even the most experienced social scientists: The living quarters of Sally Hemings, the enslaved woman who, historians believe, gave birth to six of Jefferson’s children.

“This discovery gives us a sense of how enslaved people were living. Some of Sally’s children may have been born in this room,” said Gardiner Hallock, director of restoration for Jefferson’s mountaintop plantation, standing on a red-dirt floor inside a dusty rubble-stone room built in 1809. “It’s important because it shows Sally as a human being — a mother, daughter, and sister — and brings out the relationships in her life.”

Hemings’ living quarters was adjacent to Jefferson’s bedroom but she remains something of an enigma: there are only four known descriptions of her. Enslaved blacksmith Isaac Granger Jefferson recalled that Hemings was “mighty near white . . . very handsome, long straight hair down her back.”

Her room — 14 feet, 8 inches wide and 13 feet long — went unnoticed for decades. The space was converted into a men’s bathroom in 1941, considered by some as the final insult to Hemings’ legacy. (more)

The Slave Roots of Square Dancing

What’s the world’s whitest form of dance? You would be forgiven for answering “square dancing.” Designated as the official state folk dance of 31 states, square dancing is not exactly revered for its racial diversity—and pop culture portrayals lean heavily on a mythology of reeling white farmers, not people of color. But the dance style’s lily-white reputation hides something unexpected, writes Philip A. Jamison: A deep African-American history that’s rooted in a legacy of slavery.

The connection can be found in the “callers” who prompt dancers to adopt different figures like the do-si-do and allemande—and the way in which the dances themselves became an American art form. Square dances grew out of European country or contra dances and reels exported from Scotland and England. And as white colonists learned new dances and modified old ones, many relied on black slaves to perform their music. (more)

Related: “Square Dance Calling: The African-American Connection“

TIPHC Bookshelf

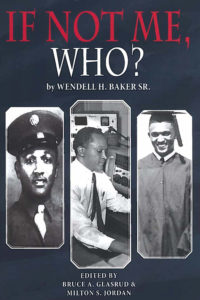

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “If Not Me, Who?, What One Man Accomplished in His Battle for Equality,” by Wendell H. Baker, Sr., edited by Bruce A. Glasrud and Milton Jordan.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “If Not Me, Who?, What One Man Accomplished in His Battle for Equality,” by Wendell H. Baker, Sr., edited by Bruce A. Glasrud and Milton Jordan.

If Not Me, Who? What One Man Accomplished in His Battle for Equality covers the life of civil rights activist and civic leader Wendell H. Baker Sr. from his birth to eighty plus years of age. Both Baker’s life and his book were singularly critical achievements.

This newly edited edition of Baker’s If Not Me, Who? includes materials from two other authors—retired Texas Southern University scholar Naomi W. Lede, whose work originally was also published in Baker’s original book, and political leader and consultant James A. Baker, who learned from Wendell Baker and his brother that they were distant cousins.

Wendell Harold Baker (1922-2013) played a crucial role in the civil rights movement in Walker County where he graduated with honors from Huntsville’s Samuel Walker Houston High School in 1939. Beginning in 1963, Baker played a leading role in the African American campaigns for voting rights, school desegregation, and integration of public accommodations in his local community. He formed the Walker County Voters League and, with his wife Augusta, paid the poll taxes for dozens of African Americans to vote. He was a key supporter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its affiliated group Huntsville Action for Youth (HA-YOU), backing their efforts to desegregate the downtown business district in 1965. And, perhaps most importantly, Baker pushed for public school desegregation in both the Huntsville Independent School District and at Sam Houston State Teachers College, now Sam Houston State University.

This Week in Texas Black History, July 2-8

3 – Ruth J. Simmons was born on this day in 1945 in Grapeland and 56 years to the day was sworn in as the 18th president of Brown University in 2001, becoming the first black president of an Ivy League school and the first female president at Brown (founded in 1764). Simmons was the youngest of 12 children born to a sharecropper father and a mother who worked as a maid. In 1995, Simmons became the first African-American woman to head a major college or university when she was selected as president of Smith College, which she led until 2001. She also served as Vice Provost at Princeton University, and a Provost at Spelman College. Simmons graduated from Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston and Dillard University, a historically black college in New Orleans. She earned her Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures from Harvard. In June 2017, she was named interim president of Prairie View A&M University.

3 – Ruth J. Simmons was born on this day in 1945 in Grapeland and 56 years to the day was sworn in as the 18th president of Brown University in 2001, becoming the first black president of an Ivy League school and the first female president at Brown (founded in 1764). Simmons was the youngest of 12 children born to a sharecropper father and a mother who worked as a maid. In 1995, Simmons became the first African-American woman to head a major college or university when she was selected as president of Smith College, which she led until 2001. She also served as Vice Provost at Princeton University, and a Provost at Spelman College. Simmons graduated from Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston and Dillard University, a historically black college in New Orleans. She earned her Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures from Harvard. In June 2017, she was named interim president of Prairie View A&M University.

4 – On this date in 1867, the Texas Republican Party was formed at a convention in Houston with African-American delegates outnumbering whites by a total of about 150 to 20. Blacks, comprising about 90 percent of the party throughout Reconstruction, would set the foundation for the party. Forty-four black Republicans would serve in the state legislature. The second State GOP Chairman, Norris Wright Cuney, an African-American from Galveston led the Party from 1883 to 1897 and is said by historians to have held “the most important political position given to a black man of the South in the nineteenth century.”

4 – On this date in 1867, the Texas Republican Party was formed at a convention in Houston with African-American delegates outnumbering whites by a total of about 150 to 20. Blacks, comprising about 90 percent of the party throughout Reconstruction, would set the foundation for the party. Forty-four black Republicans would serve in the state legislature. The second State GOP Chairman, Norris Wright Cuney, an African-American from Galveston led the Party from 1883 to 1897 and is said by historians to have held “the most important political position given to a black man of the South in the nineteenth century.”

4 – On this date in 2003, R&B singer and composer Barry White, a Galveston native, died at age 58 of renal failure in Los Angeles. A five-time Grammy Award winner, White’s gravelly, seductive, bass voice earned him 106 gold and 41 platinum albums, 20 gold and 10 platinum singles, with worldwide sales in excess of $100 million. White had suffered with high blood pressure for many years and then diabetes.

4 – On this date in 2003, R&B singer and composer Barry White, a Galveston native, died at age 58 of renal failure in Los Angeles. A five-time Grammy Award winner, White’s gravelly, seductive, bass voice earned him 106 gold and 41 platinum albums, 20 gold and 10 platinum singles, with worldwide sales in excess of $100 million. White had suffered with high blood pressure for many years and then diabetes.

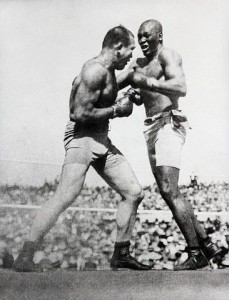

4 – In what was billed as “The Fight of the Century,” Galveston’s Jack Johnson soundly defeated Jim Jeffries, “The Great White Hope,” on this day in 1910 before a mostly white crowd of 22,000 fans in Reno, Nevada to remain as world heavyweight champion. Jeffries came out of a five-year retirement from his undefeated career to fight the racially reviled Johnson. Jeffries said, “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.” Promoters incited the crowd to chant “kill the nigger.” However, the bout was scheduled for 45 rounds, but was stopped in the 15th after Johnson twice knocked Jeffries down. The outcome produced race riots in dozens of cities with some of the incidents the result of whites interrupting celebrations of jubilant blacks. Police also interrupted several attempted lynchings.

4 – In what was billed as “The Fight of the Century,” Galveston’s Jack Johnson soundly defeated Jim Jeffries, “The Great White Hope,” on this day in 1910 before a mostly white crowd of 22,000 fans in Reno, Nevada to remain as world heavyweight champion. Jeffries came out of a five-year retirement from his undefeated career to fight the racially reviled Johnson. Jeffries said, “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.” Promoters incited the crowd to chant “kill the nigger.” However, the bout was scheduled for 45 rounds, but was stopped in the 15th after Johnson twice knocked Jeffries down. The outcome produced race riots in dozens of cities with some of the incidents the result of whites interrupting celebrations of jubilant blacks. Police also interrupted several attempted lynchings.

6 – In 1944, at Fort Hood Army Post in Killeen, Lt. Jackie Robinson refused to move to the back of a post bus and was taken into custody by military police, an incident that would lead to his court-martial. Three years before he would break the color line in Major League Baseball, Robinson was charged with insubordination, disturbing the peace, drunkenness (he did not drink), conduct unbecoming an officer, and refusing to obey the lawful orders of a superior officer. Robinson, serving in a support role for the all-black 761st Tank Battalion (the Army’s first such unit), would be acquitted a month later by an all-white panel of nine officers. (See, National Archives: “Jim Crow, Meet Lieutenant Robinson, A 1944 Court-Martial“, and The History Reader, “The Court Martial of Jackie Robinson.”)

6 – In 1944, at Fort Hood Army Post in Killeen, Lt. Jackie Robinson refused to move to the back of a post bus and was taken into custody by military police, an incident that would lead to his court-martial. Three years before he would break the color line in Major League Baseball, Robinson was charged with insubordination, disturbing the peace, drunkenness (he did not drink), conduct unbecoming an officer, and refusing to obey the lawful orders of a superior officer. Robinson, serving in a support role for the all-black 761st Tank Battalion (the Army’s first such unit), would be acquitted a month later by an all-white panel of nine officers. (See, National Archives: “Jim Crow, Meet Lieutenant Robinson, A 1944 Court-Martial“, and The History Reader, “The Court Martial of Jackie Robinson.”)

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Big People, Big Moments,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.