In the Alamo’s shadow

For one moment in time, a young black man captivated an audience comprised mainly of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence. The man’s name was Joe, an American-born slave, and one of the few survivors of the March 6,1836, Battle of the Alamo.

Joe’s account of the grisly battle solved the mystery of the besieged Alamo garrison for the Texas Revolutionary leaders, many of whom had had friends and relatives within its walls. His story also spelled out the gravity of the situation for the Texas cabinet as the invading Mexican Army crossed the Texas frontier.

Over 161 years later, Joe’s story has an impact of a different kind.

Slavery was the only life known to Joe, who was born into bondage somewhere in the southern region of the United States around the year 1813. He was sold in 1834 to William Barrett Travis, and it was by his side Joe was thrust into one of the most heroic chapters in Texas history. (read more)

Above image: In this sketch by artist Gary Zaboly, a wounded Joe is forced at the point of a bayonet to identify key members of the Alamo garrison after the final attack of March 6, 1836.

Related story: African Americans and the battle for the Alamo

After Slavery, Searching For Loved Ones In Wanted Ads

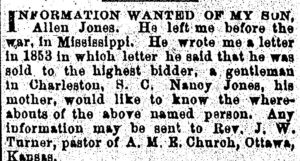

(NPR) In the waning years of the Civil War, advertisements like this began appearing in newspapers around the country:

(NPR) In the waning years of the Civil War, advertisements like this began appearing in newspapers around the country:

“INFORMATION WANTED By a mother concerning her children.

“Mrs. Elizabeth Williams, who now resides in Marysville, California was formerly owned together with her children, vis: Lydia, William, Allen, and Parker, by one John Petty, who lived about six miles from the town of Woodbury, Franklin County, Tennessee. At that time she was the the wife of Sandy Rucker, and was familiarly known as Betsy, sometimes called Betsy Petty.

“About twenty-five years ago, the mother was sold to Mr. Marshal Stroud, by whom, some twelve or fourteen years later, she was, for the second time since purchased by him, taken to Arkansas. She has never seen the above named children since. Any information given concerning them, however, will be gratefully received by one whose love for her children survives the bitterness and hardship of many long years spent in slavery.”

More than 900 of these “Information Wanted” notices — placed by African-Americans separated from family members by war, slavery and emancipation — have been digitized in a project called Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery, a collaboration between Villanova University’s graduate history program and Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.

The ads, which date from 1863 to 1902, come from six newspapers: Philadelphia’s Christian Recorder, the newspaper of the AME Church; New Orleans’ Black Republican, Nashville’s The Colored Tennessean, Charleston’s South Carolina Leader, the Free Men’s Press of Galveston, Texas, and Cincinnati’s The Colored Citizen. (read more and listen to broadcast)

A History of Race and Racism in America, in 24 Chapters

(New York Times) Many Americans might not know the more polemical side of race writing in our history. The canon of African-American literature is well established. Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, James Baldwin are familiar figures. Far less so is Samuel Morton (champion of the obsolete theory of polygenesis) or Thomas Dixon (author of novels romanticizing Klan violence). It is tempting to think that the influence of those dusty polemics ebbed as the dust accumulated. But their legacy persists, freshly shaping much of our racial discourse.

(New York Times) Many Americans might not know the more polemical side of race writing in our history. The canon of African-American literature is well established. Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, James Baldwin are familiar figures. Far less so is Samuel Morton (champion of the obsolete theory of polygenesis) or Thomas Dixon (author of novels romanticizing Klan violence). It is tempting to think that the influence of those dusty polemics ebbed as the dust accumulated. But their legacy persists, freshly shaping much of our racial discourse.

On the occasion of Black History Month, (Ibram X. Kendii) selected the most influential books on race and the black experience published in the United States for each decade of the nation’s existence — a history of race through ideas, arranged chronologically on the shelf. (In many cases, (he’s) added a complementary work, noted with an asterisk.) Each of these books was either published first in the United States or widely read by Americans. They inspired — and sometimes ended — the fiercest debates of their times: debates over slavery, segregation, mass incarceration. They offered racist explanations for inequities, and antiracist correctives. Some — the poems of Phillis Wheatley, the memoir of Frederick Douglass — stand literature’s test of time. Others have been roundly debunked by science, by data, by human experience. No list can ever be comprehensive, and “most influential” by no means signifies “best.” But (he) would argue that together, these works tell the history of anti-black racism in the United States as painfully, as eloquently, as disturbingly as words can. In many ways, they also tell its present. (read more)

Pictured: Clockwise, from top left: Phillis Wheatley, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Alice Walker, Michelle Alexander, Margaret Mitchell, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Thomas Jefferson. Credit Hulton Archive/Getty Images (Stowe); Associated Press (Walker); Getty Images North America (Alexander); Atlanta History Center (Mitchell); Bettmann/Corbis/Associated Press Images (Burroughs); Hulton Archive/Getty Images (Jefferson)

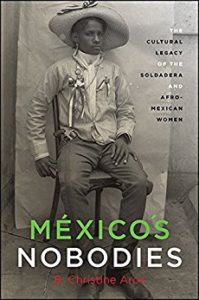

Mexico’s Nobodies: The Cultural Legacy of the Soldadera and Afro-Mexican Women

2016 Victoria Urbano Critical Monograph Book Prize, presented by the International Association of Hispanic Feminine Literature and Culture

2016 Victoria Urbano Critical Monograph Book Prize, presented by the International Association of Hispanic Feminine Literature and Culture

The book analyzes cultural materials that grapple with gender and blackness to revise traditional interpretations of Mexicanness.

México’s Nobodies examines two key figures in Mexican history that have remained anonymous despite their proliferation in the arts: the soldadera and the figure of the mulata. B. Christine Arce unravels the stunning paradox evident in the simultaneous erasure (in official circles) and ongoing fascination (in the popular imagination) with the nameless people who both define and fall outside of traditional norms of national identity. The book traces the legacy of these extraordinary figures in popular histories and legends, the Inquisition, ballads such as “La Adelita” and “La Cucaracha,” iconic performers like Toña la Negra, and musical genres such as the son jarocho and danzón. This study is the first of its kind to draw attention to art’s crucial role in bearing witness to the rich heritage of blacks and women in contemporary México.

“No one has written as lovingly and profusely on Mexican minorities as the wonderful B. Christine Arce. Here she writes about soldaderas, women of color, and camp followers—the courageous women who followed the troops during the Mexican Revolution. Without these women, soldiers would have deserted and the men would have run back home. Arce has not only captured the essence of Mexican women but also of Afro-Mexicans, who are typically forgotten and purposefully neglected.” — Elena Poniatowska, author of Massacre in Mexico

B. Christine Arce is Assistant Professor of Latin American Literature and Culture at the University of Miami.

Cornell University posts online a vast archive of historical photographs of African Americans

Cornell University posts online a vast archive of historical photographs of African Americans

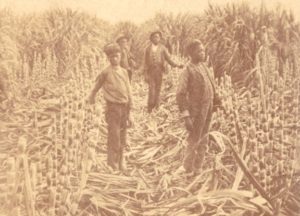

(The Journal of Blacks In Higher Education) Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, has recently made available online its Loewentheil Collection of African American Photographs. The collection was donated to the university by Stephan and Beth Loewentheil in 2012.

The collection includes 645 images, spanning the years from 1860 to the 1960s. Included are photographs of some famous African Americans including Dr. Martin Luther Jr. and Muhammad Ali. But most of the photographs are images of everyday life in the African American community. The collection can be searched by date, geographic location, photographer, and subject matter.

Among the earliest images in the collection is a photograph (right) showing a group of young African American slaves on a plantation in Louisiana.

TIPHC Bookshelf

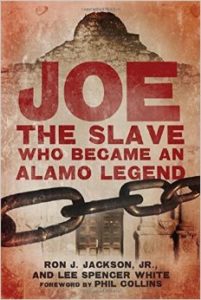

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend,” by Ron J. Jackson, Jr. and Lee Spencer White.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend,” by Ron J. Jackson, Jr. and Lee Spencer White.

If we do in fact “remember the Alamo,” it is largely thanks to one person who witnessed the final assault and survived: the commanding officer’s slave, a young man known simply as Joe. What Joe saw as the Alamo fell, recounted days later to the Texas Cabinet, has come down to us in records and newspaper reports. But who Joe was, where he came from, and what happened to him have all remained mysterious until now. In a remarkable feat of historical detective work, authors Ron J. Jackson, Jr., and Lee Spencer White have fully restored this pivotal yet elusive figure to his place in the American story.

The twenty-year old Joe stood with his master, Lieutenant Colonel Travis, against the Mexican army in the early hours of March 6, 1836. After Travis fell, Joe watched the battle’s last moments from a hiding place. He was later taken first to Bexar and questioned by Santa Anna about the Texan army, and then to the revolutionary capitol, where he gave his testimony with evident candor.

With these few facts in hand, Jackson and White searched through plantation ledgers, journals, memoirs, slave narratives, ship logs, newspapers, letters, and court documents. Their decades long effort has revealed the outline of Joe’s biography, alongside some startling facts: most notably, that Joe was the younger brother of the famous escaped slave and abolitionist narrator William Wells Brown, as well as the grandson of legendary trailblazer Daniel Boone. This book traces Joe’s story from his birth in Kentucky through his life in slavery—which, in a grotesque irony, resumed after he took part in the Texans’ battle for independence—to his eventual escape and disappearance into the shadows of history.

Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend recovers a true American character from obscurity and expands our view of events central to the emergence of Texas.

This Week In Texas Black History

26 – Heman Sweatt, accompanied by a delegation from the NAACP, met with University of Texas president Theophilus S. Painter and other university officials on this day in 1946 to present a formal request for Sweatt’s admission to the UT law school. The legal case resulting from this request, Sweatt v. Painter, became a landmark civil rights decision, one of several that struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” educational facilities. Sweatt finally registered at the school on September 19, 1950.

26 – Heman Sweatt, accompanied by a delegation from the NAACP, met with University of Texas president Theophilus S. Painter and other university officials on this day in 1946 to present a formal request for Sweatt’s admission to the UT law school. The legal case resulting from this request, Sweatt v. Painter, became a landmark civil rights decision, one of several that struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” educational facilities. Sweatt finally registered at the school on September 19, 1950.

27 – Negro Leagues pitcher Hilton Smith was born on this day in 1907 in Giddings. He played baseball at Prairie View A&M College and then, in 1931 with the Austin Black Senators and in 1932 the Monroe (La.) Monarchs. In 1937, he joined the Kansas City Monarchs, of the newly formed Negro American League and played there until 1948. With Kansas City, he frequently came on in relief of the great Satchel Paige. Smith was named to six consecutive East-West All-star Games (’37-42) and won 20 or more games in each of his 12 seasons with Kansas City, including a 93-11 record over a four-year span (’39-42). He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001. Buck O’Neil, his teammate and close friend said of him, “From 1940 to 1946, Hilton Smith might have been the greatest pitcher in the world.”

27 – Negro Leagues pitcher Hilton Smith was born on this day in 1907 in Giddings. He played baseball at Prairie View A&M College and then, in 1931 with the Austin Black Senators and in 1932 the Monroe (La.) Monarchs. In 1937, he joined the Kansas City Monarchs, of the newly formed Negro American League and played there until 1948. With Kansas City, he frequently came on in relief of the great Satchel Paige. Smith was named to six consecutive East-West All-star Games (’37-42) and won 20 or more games in each of his 12 seasons with Kansas City, including a 93-11 record over a four-year span (’39-42). He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001. Buck O’Neil, his teammate and close friend said of him, “From 1940 to 1946, Hilton Smith might have been the greatest pitcher in the world.”

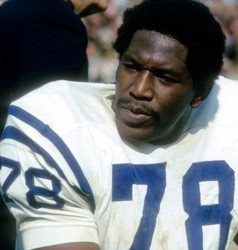

28 – On this date in 1945, All-Pro defensive end Charles “Bubba” Smith was born in Orange. Smith played for his father, Willie Ray Smith, at Beaumont Charlton-Pollard HS and attended Michigan State University where he was a two-time All-American defensive end. Smith was the first pick of the 1967 NFL draft by the Baltimore Colts, and was a member of their Super Bowl V winning team. During his nine-year career, he also played with the Oakland Raiders and the Houston Oilers. After football, Smith became an actor, most noted for his roles in six “Police Academy” films. In 1988, he was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame.

28 – On this date in 1945, All-Pro defensive end Charles “Bubba” Smith was born in Orange. Smith played for his father, Willie Ray Smith, at Beaumont Charlton-Pollard HS and attended Michigan State University where he was a two-time All-American defensive end. Smith was the first pick of the 1967 NFL draft by the Baltimore Colts, and was a member of their Super Bowl V winning team. During his nine-year career, he also played with the Oakland Raiders and the Houston Oilers. After football, Smith became an actor, most noted for his roles in six “Police Academy” films. In 1988, he was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame.

March

3 – On this date in 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill was passed by the U.S. Congress. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was a branch of the U.S. Army created to provide practical aid to 4,000,000 newly freed Black Americans in their transition from slavery to freedom. The agency also helped whites left homeless by the Civil War. The Freedmen’s Bureau operated in Texas from late September 1865 until July 1870.

3 – On this date in 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill was passed by the U.S. Congress. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was a branch of the U.S. Army created to provide practical aid to 4,000,000 newly freed Black Americans in their transition from slavery to freedom. The agency also helped whites left homeless by the Civil War. The Freedmen’s Bureau operated in Texas from late September 1865 until July 1870.

4 — In 1960, on this day, students from Texas Southern University, led by Eldrewey Stearns, held Houston’s first sit-in protest at a Weingarten grocery store lunch counter. This protest introduced a new aspect in the struggle for equal rights in Houston and helped dismantle segregation in the city. By Aug. 25, 1960, supermarkets, drugstores and hotels had desegregated.

4 — In 1960, on this day, students from Texas Southern University, led by Eldrewey Stearns, held Houston’s first sit-in protest at a Weingarten grocery store lunch counter. This protest introduced a new aspect in the struggle for equal rights in Houston and helped dismantle segregation in the city. By Aug. 25, 1960, supermarkets, drugstores and hotels had desegregated.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Bearing His Cross,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.