We invite you to use the occasion of the museum’s opening to Lift Your Voice and tell the nation about the great work you are doing to celebrate African American History and Culture in your hometown. Co-brand your event/activity with the museum and show how your organization exists as part of a national story.

Register your event (free) today and be acknowledged as a supporter of our Lift Every Voice Campaign. Registered events will be featured on the museum’s website as a global directory of celebrations. Events or activities can occur anytime within the inaugural year, now through December 2017.

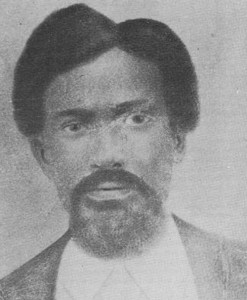

The Literary Battle for Nat Turner’s Legacy

From Vanity Fair: The Confessions of Nat Turner dropped off syllabuses long ago, replaced by such other tours de force as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Edward P. Jones’s The Known World. Yet Styron’s subject is fresher than ever. Antebellum slavery is on many minds—its sins and crimes, its irreducible impact, its consequences that divide us to this day, evident in the recent bloodshed in Ferguson and Baltimore, Dallas and Baton Rouge, and in the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

From Vanity Fair: The Confessions of Nat Turner dropped off syllabuses long ago, replaced by such other tours de force as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Edward P. Jones’s The Known World. Yet Styron’s subject is fresher than ever. Antebellum slavery is on many minds—its sins and crimes, its irreducible impact, its consequences that divide us to this day, evident in the recent bloodshed in Ferguson and Baltimore, Dallas and Baton Rouge, and in the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Every week, it seems, another headline screams at us: the Confederate flags at last removed from southern statehouses after the mass murder of African-American churchgoers in Charleston; the Jesuit founders of Georgetown University who paid off their debts by sending slaves, including infants, to hellish plantations in the Deep South; the battles over John C. Calhoun at Yale and dormitory “house masters” at Harvard. The legacy of slavery informs recent novels (Homegoing; Grace) and movies (The Free State of Jones; Ava DuVernay’s documentary The 13th) as well as the new National Museum of African American History & Culture, which opens in Washington in September.

Meanwhile, Styron’s protagonist, Nat Turner, has been revived—in The Birth of a Nation, a feature, set to premiere in October, that is already being discussed as a serious contender for next year’s Oscar. Its star, director, and screenwriter, Nate Parker, is an African-American who grew up in Virginia, as did Turner and Styron. (At 36, Parker is one year older than Styron was when he began work on his novel in 1960.) And in some respects the movie fulfills Styron’s original ambitions. Parker, who spent years researching Turner’s life and times, is dismissive of Styron’s effort, echoing many back in the 60s. “Styron’s novel ignited a much-deserved criticism as he annihilated Turner’s character. . . ,” says Parker. “

But this harsh judgment rests on an ineradicable truth. It was William Styron—the product of what he wryly termed an “absolutely impeccable WASP background”—who dug up the buried nugget of Nat Turner’s rebellion and polished it into a modern parable. This was the reason for its initial praise—from black readers as well as white. But it also became the reason for the startling reversal of fortune that followed. The Confessions of Nat Turner remains the most vivid case of a literary work that arrived in glory—critical praise; a Pulitzer Prize; the top slot on the New York Times best-seller list—only to be consumed by larger forces that its creator, for all his imaginative powers, didn’t see coming. In August 1967, the Times would describe Styron, without irony, as an “expert in the Negro condition.” Six months later many were regarding him as a frothing racist, accused—as Styron bitterly recalled—of having written “a malicious work, deliberately falsifying history.” He had, as he later put it, “unwittingly created one of the first politically incorrect texts of our time.”

Today the furor over The Confessions of Nat Turner is more relevant than ever. The questions Styron struggled with continue to provoke us. Who “owns” American history? Who gets to tell which stories—and why? Is artistic license a hallowed precept or a stale presumption? Bill Styron learned the answers in the most direct and painful way. (Read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Make Haste Slowly: Moderates, Conservatives, and School Desegregation in Houston,” by William Henry Kellar.

When faced by the Court-ordered “all deliberate speed” time frame for school desegregation, a fearful Houston school board member urged the city to “make haste slowly,” in order for the school system to receive decisions based on sound judgment and discretion.

Houston, Texas, had what may have been the largest racially segregated “Jim Crow” public school system in the United States when the Supreme Court declared the practice unconstitutional in 1954. Ultimately, helped by members of its business community, Houston did desegregate its public schools and did so peacefully, without making the city a battleground of racial violence.

In Make Haste Slowly, William Henry Kellar provides the first extensive examination of the development of Houston’s racially segregated public school system, the long fight for school desegregation, and the roles played by various community groups, including the HISD Board of Education, in one of the most significant stories of the civil rights era.

This Week In Texas Black History, July 31-Aug. 6

31 – Frank Robinson, the first black manager in Major League Baseball, was born on this day in Beaumont. Robinson grew up in Oakland and played the bulk of his career with the Cincinnati Reds and Baltimore Orioles. He won the triple crown — leading the league in home runs (49), runs batted in (122), and batting average (.316) — in 1966, and became manager of the Cleveland Indians in 1975. A Baseball Hall of Famer, his 586 career home runs are ninth all-time in MLB.

31 – Frank Robinson, the first black manager in Major League Baseball, was born on this day in Beaumont. Robinson grew up in Oakland and played the bulk of his career with the Cincinnati Reds and Baltimore Orioles. He won the triple crown — leading the league in home runs (49), runs batted in (122), and batting average (.316) — in 1966, and became manager of the Cleveland Indians in 1975. A Baseball Hall of Famer, his 586 career home runs are ninth all-time in MLB.

August

1 – On this day in 1948, football and track star Clifford Branch was born in Houston. At Evan E. Worthing High School, Branch was All-District in football (1966), but was also the first schoolboy in Texas history to run the 100-yard dash in 9.3 seconds. He was the state champion in the 100-yard dash (1965) and the 220-yard dash (1966). He attended the University of Colorado where he was an All-American wide receiver (1971) and the 1972 NCAA 100-meter champion with a record time of 10.0. Branch was selected in the fourth round of the National Football League Draft by the Oakland Raiders and played his entire pro career (1972-85) with the team, including three Super Bowl titles. He was named first-team All-Pro three times and finished his career with 501 receptions for 8,685 yards and 67 touchdowns. He is a member of the Prairie View Interscholastic League Hall of Fame.

1 – On this day in 1948, football and track star Clifford Branch was born in Houston. At Evan E. Worthing High School, Branch was All-District in football (1966), but was also the first schoolboy in Texas history to run the 100-yard dash in 9.3 seconds. He was the state champion in the 100-yard dash (1965) and the 220-yard dash (1966). He attended the University of Colorado where he was an All-American wide receiver (1971) and the 1972 NCAA 100-meter champion with a record time of 10.0. Branch was selected in the fourth round of the National Football League Draft by the Oakland Raiders and played his entire pro career (1972-85) with the team, including three Super Bowl titles. He was named first-team All-Pro three times and finished his career with 501 receptions for 8,685 yards and 67 touchdowns. He is a member of the Prairie View Interscholastic League Hall of Fame.

2 – Legendary Prairie View A&M football coach William J. “Billy” Nicks was born on this day in 1905 in Griffin, Ga. He attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. Nicks returned to his alma mater as head football coach on three different occasions — 1930-35, 1937-39 and 1941-42. His 1941 team was named black college national champion. Nicks began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC school, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. His overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. Nicks is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

2 – Legendary Prairie View A&M football coach William J. “Billy” Nicks was born on this day in 1905 in Griffin, Ga. He attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. Nicks returned to his alma mater as head football coach on three different occasions — 1930-35, 1937-39 and 1941-42. His 1941 team was named black college national champion. Nicks began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC school, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. His overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. Nicks is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

2 — In 1944, 15 months before he would break Major League Baseball‘s color barrier, the court martial of 2nd Lt. Jackie Robinson was held on this day at Fort Hood in Killeen. On July 6, Robinson had refused to move to the “colored section” in the back of a post bus. Among the several resulting charges against Robinson were conduct unbecoming an officer. The trial lasted four hours and after brief deliberations, a panel of nine officers (one of them black) found Robinson not guilty of all charges. Robinson had been morale officer for the all-black 761st Tank Battalion but, by the trial’s end, the unit had departed for Europe where they would perform heroically with Gen. Patton’s Third Army. Robinson was transferred to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he coached black athletic teams until his honorable discharge in November 1944. He played the 1945 season with the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs and in October of that year signed to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was sent to their top Minor League affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Robinson’s debut as MLB’s first black player came on April 15, 1947, at age 28.

2 — In 1944, 15 months before he would break Major League Baseball‘s color barrier, the court martial of 2nd Lt. Jackie Robinson was held on this day at Fort Hood in Killeen. On July 6, Robinson had refused to move to the “colored section” in the back of a post bus. Among the several resulting charges against Robinson were conduct unbecoming an officer. The trial lasted four hours and after brief deliberations, a panel of nine officers (one of them black) found Robinson not guilty of all charges. Robinson had been morale officer for the all-black 761st Tank Battalion but, by the trial’s end, the unit had departed for Europe where they would perform heroically with Gen. Patton’s Third Army. Robinson was transferred to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he coached black athletic teams until his honorable discharge in November 1944. He played the 1945 season with the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs and in October of that year signed to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was sent to their top Minor League affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Robinson’s debut as MLB’s first black player came on April 15, 1947, at age 28.

4 – On this day in 1840, minister and Republican State Senator Matthew Gaines was born into slavery in Pineville, La. In 1863, he was sold to a planter in Fredericksburg where he worked as a blacksmith and a sheepherder. After emancipation, he relocated to Washington County where he became a leader of the black community, and was elected as a state senator during Reconstruction to represent the Sixteenth District. He was a staunch proponent for education, prison reform, the protection of blacks at the polls, the election of blacks to public office, and tenant-farming reform.

4 – On this day in 1840, minister and Republican State Senator Matthew Gaines was born into slavery in Pineville, La. In 1863, he was sold to a planter in Fredericksburg where he worked as a blacksmith and a sheepherder. After emancipation, he relocated to Washington County where he became a leader of the black community, and was elected as a state senator during Reconstruction to represent the Sixteenth District. He was a staunch proponent for education, prison reform, the protection of blacks at the polls, the election of blacks to public office, and tenant-farming reform.

4 — District Court Judge Ben Connally labeled the Houston school board‘s desegregation plan a “palpable sham and subterfuge” on this day in 1960. Houston’s 173 schools comprised the largest segregated school district in the U.S., and in 1957 Connally ordered the schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” However, in August, 1959, the board revealed in a 373-page report to the Court that it had no desegregation plan and requested additional time to prepare one. Connally ordered the board to submit a plan by June 1, 1960. It was that plan which enraged Connally. In it, the board sought to integrate only three schools, but stated that no child need attend the integrated schools. As a result, Connally ordered desegregation to commence in all first grades in September 1960 and to proceed at one grade per year thereafter. The board’s attitude may have been typified by parliamentarian Bertie Maughmer who had won election to the board in 1956 proudly declaring: “I’d rather go to jail than see my kids go to school with niggers.”

4 — District Court Judge Ben Connally labeled the Houston school board‘s desegregation plan a “palpable sham and subterfuge” on this day in 1960. Houston’s 173 schools comprised the largest segregated school district in the U.S., and in 1957 Connally ordered the schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” However, in August, 1959, the board revealed in a 373-page report to the Court that it had no desegregation plan and requested additional time to prepare one. Connally ordered the board to submit a plan by June 1, 1960. It was that plan which enraged Connally. In it, the board sought to integrate only three schools, but stated that no child need attend the integrated schools. As a result, Connally ordered desegregation to commence in all first grades in September 1960 and to proceed at one grade per year thereafter. The board’s attitude may have been typified by parliamentarian Bertie Maughmer who had won election to the board in 1956 proudly declaring: “I’d rather go to jail than see my kids go to school with niggers.”

5 – On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

5 – On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

6 – President Lyndon Johnson, on this day signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African American and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests, but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

6 – President Lyndon Johnson, on this day signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African American and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests, but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Good  win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Who speaks for us? Read it

win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Who speaks for us? Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.