How Black Suffragists Fought for the Right to Vote and a Modicum of Respect

Hallie Quinn Brown and Other “Homespun Heroines”

(neh.gov) Hallie Quinn Brown knew the power of black women and urged anyone who heard her to let it flourish. Read her remarks from 1889 and you might believe she saw the future or at least had the capacity to call it into being: “I believe there are as great possibilities in women as there are in men. . . . We are marching onward grandly. . . . We love to think of the great women of our race—the mothers who have struggled through poverty to educate their children. . . . There are many wives who are now helping to educate their husbands at school, by taking in sewing and washin. . . I believe in equalizing the matter. Instead of going to school a whole year, he ought to stay at home one half, and send his wife the other six months. . . . I repeat, we want a grand and noble womanhood, scattered all over the land. There is a great vanguard of scholars and teachers of our sex who are at the head of institutions of learning all over the country. We need teachers, lecturers of force and character to help to teach this great nation of women.”

These remarks, delivered before a conference of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, marked a debut for Brown as an advocate of women’s rights, including the right to vote. If finding the start of a suffragist’s career in a church sanctuary surprises, it is only because the route to women’s suffrage taken by black women is still too often relegated to the margins or obscured by misunderstanding. Consider how black women did not take part in the mythical 1848 women’s meeting in Seneca Falls, New York. When we look for them in that year, we find that, instead, some of them were already at work demanding women’s rights, but they were doing so in black churches rather than in women’s conventions. And what about 1920 and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment? The study of that hallmark moment reveals that, while some black women in the North and West had reason to celebrate, it was but a brief pause in their ongoing struggle for voting rights. Especially for black women in southern states, the struggle for the vote extended for decades more, to 1965, when the Voting Rights Act would finally topple barriers constructed by Jim Crow. (more)

How Phillis Wheatley Was Recovered Through History

For decades, a white woman’s memoir shaped our understanding of America’s first Black poet. Does a new book change the story?

(newyorker.com) Though Phillis (Wheatley) left a rich paper trail of poems and letters, she never recorded her own account of her life, and, in her writings, which brim with her spiritual and political ideas, biographical details are sparse. For those, scholars have had to rely on a memoir published in 1834, fifty years after the poet’s death, by Margaretta Matilda Odell, a white woman who claimed to be a “collateral descendant” of Susanna Wheatley.

(newyorker.com) Though Phillis (Wheatley) left a rich paper trail of poems and letters, she never recorded her own account of her life, and, in her writings, which brim with her spiritual and political ideas, biographical details are sparse. For those, scholars have had to rely on a memoir published in 1834, fifty years after the poet’s death, by Margaretta Matilda Odell, a white woman who claimed to be a “collateral descendant” of Susanna Wheatley.

Odell neglects to mention the horrors of Phillis’s transatlantic journey, and she finds no fault with the Wheatleys’ treatment of those they enslaved. (Phillis was separated from the rest of the family’s slaves, and told not to associate with them.) And Odell’s Phillis is distinctly lacking in agency. Odell’s many errors were repeated for decades, shaping receptions of Phillis through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But a new book, “The Age of Phillis,” by the poet and professor Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, presents a different story. Jeffers suggests that Odell’s memoir created a “pesky ‘House Negro’ narrative” that framed Phillis Wheatley as domestic, apolitical, and acquiescent. Frustrated that literary history entrusted the story of America’s first Black poet to a white woman, Jeffers spent years hunting through Massachusetts archives. (more)

Shirley Chisholm blazed the way for every Black woman Biden is considering for VP

Rep. Shirley Chisholm (D-N.Y.) presents her views in Washington on June 24, 1972, before the panel drafting the platform for the Democratic National Convention. (James Palmer/AP)

(washingtonpost.com) On Jan. 25, 1972, Rep. Shirley Chisholm of New York stood on a platform in a Baptist church in her congressional district in Brooklyn. Behind a dozen microphones, she waved to the crowd and took a leap into history as she declared her bid for the Democratic nomination for the presidency of the United States of America.

“I am not the candidate for Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and I’m equally proud of that. I am not the candidate of any political bosses or fat cats or special interests,” Chisholm said in a clipped voice.

“I stand here now without endorsement from many big-name politicians or celebrities or any other kind of prop. I do not intend to offer you the tired and glib cliches that have too long been an accepted part of our political life. I am the candidate of the people of America.”

The first Black woman elected to Congress ran against Sen. George McGovern (S.D.), who would go on to win the Democratic nomination but lose in a dramatic landslide to Republican Richard Nixon.

Chisholm’s presidential bid would be remembered for the power of her speeches, her fortitude, and her brutal honesty about racism, sexism politics and the state of the country. Chisholm’s defiant campaign, which inspired a number of women to run for public office, has received renewed attention, as Joe Biden considers a number of Black women as his running mate. (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Make Haste Slowly — Moderates, Conservatives, and School Desegregation in Houston,” by William Henry Kellar.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Make Haste Slowly — Moderates, Conservatives, and School Desegregation in Houston,” by William Henry Kellar.

When faced by the Court-ordered “all deliberate speed” time frame for school desegregation, a fearful Houston school board member urged the city to “make haste slowly,” in order for the school system to receive decisions based on sound judgment and discretion.

Houston, Texas, had what may have been the largest racially segregated “Jim Crow” public school system in the United States when the Supreme Court declared the practice unconstitutional in 1954. Ultimately, helped by members of its business community, Houston did desegregate its public schools and did so peacefully, without making the city a battleground of racial violence.

In Make Haste Slowly, William Henry Kellar provides the first extensive examination of the development of Houston’s racially segregated public school system, the long fight for school desegregation, and the roles played by various community groups, including the HISD Board of Education, in one of the most significant stories of the civil rights era.

Drawing on archival records, HISD School Board minutes, interviews with participants in the process, the oral history collection of the Houston Metropolitan Research Center, and a variety of other sources, Kellar constructs a detailed account of the development of Houston’s segregated public school system and the struggle of Houston’s African American community against the oppression of racial discrimination in the city.

Kellar shows that, while Houston desegregated its public school system peacefully, the limited integration that originally occurred served only to delay equal access to HISD schools. Houstonians shifted from a strategy “massive resistance” to one of “massive retreat.” White flight and resegregation transformed both the community and its public schools.

Kellar concludes that forty years after the Brown decision, many of the aspirations that landmark ruling inspired have proven elusive, but the impact of the ruling on Houston has changed the face of that city and the nature of its public education dramatically and in unanticipated ways.

Make Haste Slowly fills a longtime void in the literature on the civil rights era in Texas. Those interested in Texas history and African American history will find this book essential to understanding one of the most reactionary periods in American history.

This Week in Texas Black History

Aug. 2

Legendary Prairie View A&M football coach William J. “Billy” Nicks was born on this day in 1905 in Griffin, Ga. He attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. Nicks returned to his alma mater as head football coach on three different occasions — 1930-35, 1937-39 and 1941-42. His 1941 team was named black college national champion. Nicks began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC school, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. His overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. Nicks is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

Aug. 2

In 1944, 15 months before he would break Major League Baseball‘s color barrier, the court martial of 2nd Lt. Jackie Robinson was held on this day at Fort Hood in Killeen. On July 6, Robinson had refused to move to the “colored section” in the back of a post bus. Among the several resulting charges against Robinson were conduct unbecoming an officer. The trial lasted four hours and after brief deliberations, a panel of nine officers (one of them black) found Robinson not guilty of all charges. Robinson had been morale officer for the all-black 761st Tank Battalion but, by the trial’s end, the unit had departed for Europe where they would perform heroically with Gen. Patton’s Third Army. Robinson was transferred to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he coached black athletic teams until his honorable discharge in November 1944. He played the 1945 season with the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs and in October of that year signed to play with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was sent to their top Minor League affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Robinson’s debut as MLB’s first black player came on April 15, 1947, at age 28.

Aug. 4

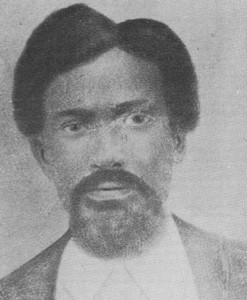

On this day in 1840, minister and Republican State Senator Matthew Gaines was born into slavery in Pineville, La. In 1863, he was sold to a planter in Fredericksburg, Texas where he worked as a blacksmith and a sheepherder. After emancipation, he relocated to Washington County where he became a leader of the black community and was elected as a state senator during Reconstruction to represent the Sixteenth District. He was a staunch proponent for education, prison reform, the protection of blacks at the polls, the election of blacks to public office, and tenant-farming reform.

Aug. 4

District Court Judge Ben Connally labeled the Houston school board‘s desegregation plan a “palable sham and subterfuge” on this day in 1960. Houston’s 173 schools comprised the largest segregated school district in the U.S., and in 1957 Connally ordered the schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” However, in August, 1959, the board revealed in a 373-page report to the Court that it had no desegregation plan and requested additional time to prepare one. Connally ordered the board to submit a plan by June 1, 1960. It was that plan which enraged Connally. In it, the board sought to integrate only three schools, but stated that no child need attend the integrated schools. As a result, Connally ordered desegregation to commence in all first grades in September 1960 and to proceed at one grade per year thereafter. The board’s attitude may have been typified by parliamentarian Bertie Maughmer who had won election to the board in 1956 proudly declaring: “I’d rather go to jail than see my kids go to school with niggers.”

District Court Judge Ben Connally labeled the Houston school board‘s desegregation plan a “palable sham and subterfuge” on this day in 1960. Houston’s 173 schools comprised the largest segregated school district in the U.S., and in 1957 Connally ordered the schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” However, in August, 1959, the board revealed in a 373-page report to the Court that it had no desegregation plan and requested additional time to prepare one. Connally ordered the board to submit a plan by June 1, 1960. It was that plan which enraged Connally. In it, the board sought to integrate only three schools, but stated that no child need attend the integrated schools. As a result, Connally ordered desegregation to commence in all first grades in September 1960 and to proceed at one grade per year thereafter. The board’s attitude may have been typified by parliamentarian Bertie Maughmer who had won election to the board in 1956 proudly declaring: “I’d rather go to jail than see my kids go to school with niggers.”

Aug. 5

On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

Aug. 6

President Lyndon Johnson, on this day, signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African Americans and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location, and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Protect and Serve (Control)

The black community’s relationship with law and order has been tenuous, at best, for generations. Sadly, I believe our society has lost sight of the original purpose of law enforcement and how that purpose has been altered in our current societal and global environments. What’s even worse, if that’s possible, is that some groups in our society still embrace the archaic and erroneous ideology that people of color are genetically inferior to those of… (more)

More Uncomfortable Truths

In February 2020, I was asked to contribute an opinion piece for the PVAMU website. I submitted an essay describing what I called an Uncomfortable Truth of Black History Month. That “truth” focused on the black community’s continual efforts to prove it is worthy of recognition as contributors to American society. Even more so, I argued, it is time the black community finally acknowledges that the subliminal need for acceptance is based on the… (more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.