The importance of black history and why it should be celebrated beyond February

Photo: Visitors tour the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images, FILE)

(ABC News) In 1925, Harvard-trained historian Carter G. Woodson, known as the “Father of Black History,” had a bold idea.

That year, he announced “Negro History Week” — a celebration of a people that many in this country at the time believed had no place in history.

The response to the event, first celebrated in February 1926, a month that included the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, was overwhelming — as educators, scholars and philanthropists stepped forward to endorse the effort. Fifty years later, coinciding with nation’s bicentennial and in the wake of the civil rights movement, the celebration was expanded to a month after President Gerald R. Ford decreed a national observance.

Since Woodson’s death in 1950, the organization that he founded, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History — now called the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) — has fought to keep his legacy alive.

Now, nearly 105 years after its founding, one of the organization’s biggest challenges is keeping people engaged beyond February.

“One cannot discuss the African American freedom struggle or the civil rights movement without paying attention to white allies who were working alongside black people,” Lionel Kimble, vice president for programs at ASALH, told ABC News. “One of the biggest issues we see, especially for those non-black folks, is that the emphasis on black history is divisive and some mistakenly label it ‘racist.'” (more)

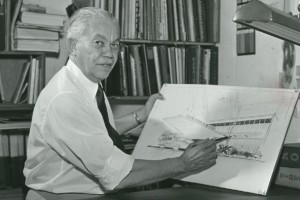

Documentary: “Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story”

(pbssocal.org) Nicknamed “Architect to the Stars,” African American architect Paul R. Williams had a life story that could have been dreamed up by a Hollywood screenwriter. Orphaned at the age of four, Williams grew up to build mansions for movie stars and millionaires in Southern California. From the early 1920s until his retirement 50 years later, Williams was one of the most successful architects in the country. His list of residential clients included Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Barbara Stanwyck, William Holden, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. And his name is associated with architectural icons like the Beverly Hills Hotel, the original MCA Headquarters Building and LAX Airport.

But at the height of his career Paul Williams wasn’t always welcome in the restaurants and hotels he designed or the neighborhoods where he built homes, because of his race. “Hollywood’s Architect: The Paul R. Williams Story” tells the compelling, but little known story, of how he used talent and perseverance to beat the odds and create a body of work that can be found from coast to coast.

After premiering on PBS stations throughout the country in February/Black History Month, 2020 the film will stream at PBSSoCal. (more)

The Remarkable Black Businesswomen Who Found Success in Segregated America

Excerpt from the new book “Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America,” by Candacy Taylor (Abrams Press).

(Time.com) For decades, the Green Book was an indispensable guide to travel for African Americans in the segregated United States. It also played a critical role in the lives of women. Whether they were traveling across the country or running a hotel, beauty shop, tourist home, or even a sex club, the Green Book helped women break out of traditional gender roles. At a time when they couldn’t get credit from a bank or even have their own bank accounts, black women found a measure of success and independence by listing their businesses in the Green Book.

(Time.com) For decades, the Green Book was an indispensable guide to travel for African Americans in the segregated United States. It also played a critical role in the lives of women. Whether they were traveling across the country or running a hotel, beauty shop, tourist home, or even a sex club, the Green Book helped women break out of traditional gender roles. At a time when they couldn’t get credit from a bank or even have their own bank accounts, black women found a measure of success and independence by listing their businesses in the Green Book.

In addition to tourist homes, the Green Book featured traditionally “female” businesses, such as hair salons and beauty colleges. There were just under 900 beauty shops listed in the Green Book during its life. Beauty salons were active, long-standing businesses in a community, providing a safe place where people could sit for hours. Amid the aroma of corrosive chemicals and the clicking of curling irons, customers could let down their hair, literally and figuratively, and spill their secrets in the comfort of cushioned vinyl.

Salon operators were not just hairstylists; they were pillars of the community. During the time salons were listed in the Green Book, some of them served as headquarters for community development, especially during the birth of the civil rights movement. At election time, stylists drove their clients to the voting booth, and since the NAACP was considered a radical organization, some clients had its literature delivered to the beauty shop instead of their homes. And you could usually find a copy of the Chicago Defender sitting on tables in the waiting area or in the magazine racks between hair dryers, next to Jet and Ebony. (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “No Way but to Fight, George Foreman and the Business of Boxing,” by Andrew R. M. Smith.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “No Way but to Fight, George Foreman and the Business of Boxing,” by Andrew R. M. Smith.

Olympic gold medalist. Two-time world heavyweight champion. Hall of Famer. Infomercial and reality TV star. George Foreman’s fighting ability is matched only by his acumen for selling. Yet the complete story of Foreman’s rise from urban poverty to global celebrity has never been told until now.

Raised in Houston’s “Bloody Fifth” Ward, battling against scarcity in housing and food, young Foreman fought sometimes for survival and other times just for fun. But when a government program rescued him from poverty and introduced him to the sport of boxing, his life changed forever.

In “No Way but to Fight,” Andrew R. M. Smith traces Foreman’s life and career from the Great Migration to the Great Society, through the Cold War and culture wars, out of urban Houston and onto the world stage where he discovered that fame brought new challenges. Drawing on new interviews with George Foreman and declassified government documents, as well as more than fifty domestic and international newspapers and magazines, Smith brings to life the exhilarating story of a true American icon. No Way but to Fight is an epic worthy of a champion.

This Week in Texas Black History

Feb. 9

On this date in 1902, civil rights activist Juanita Craft was born in Round Rock. She worked as a maid in Dallas at the Adolphus Hotel from 1925-1934 before joining the Dallas branch of the NAACP in 1935 and beginning several decades of service. She helped organize 182 branches of the NAACP in Texas and in 1944 was the first black woman in Dallas County to vote. In 1946 she was the first black woman deputized in the state to collect the poll tax. Craft also served two terms on the Dallas City Council (1975-1979).

Feb. 9

Dr. Lawrence Nixon was born on this day in 1883 in Marshall. Nixon had a successful practice in El Paso where he was a charter member of the city’s branch of the NAACP. In 1923, Nixon challenged a state law that barred African Americans from participating in the Texas Democratic Party’s white’s only electoral primaries. Nixon won two U.S. Supreme Court rulings making the primaries unconstitutional. However, it would be another 20 years before the white primary would finally be abolished.

Feb. 13

On this day in 1873, Emmett J. Scott was born in Houston. Scott was a journalist and administrator who worked for the Houston Post, but in 1894 he founded Houston’s first black newspaper, the Houston Freeman, a weekly newspaper. For many years, Scott was the personal secretary for Booker T. Washington, and during World War I was in charge of Negro affairs as a special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of War. That position made Scott the highest ranking black person in President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and led to many changes for black soldiers with many of the issues they faced and the participation of black units in World War I outlined in Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War (1919). Among the changes Scott helped to bring about were:

- The continuance of training camps for black officers and the increase in their number and an enlargement of their scope of training.

- Betterment of the general conditions in the camps where blacks are stationed in large numbers, and positive steps taken to reduce race friction to a minimum wherever soldiers of opposite races are brought into contact.

- An increase from four to 60 in the number of black Army chaplains.

- The opening of every branch of the military service to black men, on equal terms with all others, and the commissioning of many black men as officers in the Medical Corps.

- Large increase in the number of black line officers with the total increasing from less than a dozen at the beginning of the war to more than 1,200.

Feb. 13

In 1920, on this date, Rube Foster – a native of Calvert, Texas – led the founding of baseball’s first successful all-black league, the Negro National League, headquartered in Kansas City, Mo. Foster was league president, as well as manager and player (pitcher) for the Chicago American Giants. He is known as “the father of black baseball.”

Feb. 15

Dallas journalist and publicist Fay Jackson was born on this day in 1902. Jackson founded Flash in the late 1920s, the first black news magazine on the West Coast and during the 1930s she became the first black Hollywood correspondent with the Associated Negro Press (ANP). Jackson was also the ANP’s first black foreign correspondent.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Worried?

I have a confession. I’m a worrier. But I don’t worry if the Dallas Cowboys or the Houston Texans will make the playoffs, I worry about my family’s health and well being. Right now I’m especially worried about my mother and one of my brothers-in-law. Both are dealing with issues that I pray daily about. And I know I’m not supposed to worry, the Good Book teaches that if the Provider takes care of the…(more)

Football is still football

October 14th, 2019

Since we’re into the football season I thought it was time to interject my two cents. I’ve noticed several teams starting black quarterbacks these days. Some because of injury, but others have been under center since training camp. By my count, the first weekend of the National Football League season in September saw nine African…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.