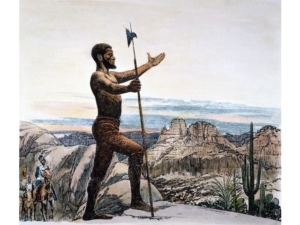

Mystery confines Estebanico, black explorer of US Southwest

(The Brownsville Herald) A black Moroccan slave who explored present-day Texas, New Mexico and Arizona with Spanish conquistadors is credited with being the first person of African descent to enter the American Southwest, but he’s all but absent from the states’ histories.

Estebanico guided the shipwrecked Spaniards through Native American communities thanks to his language and healing skills before leading a second expedition, which ended in his disappearance.

But while scholars say the American Southwest likely would not have been settled by Europeans without Estebanico, there are no parks, buildings or malls named in his honor like they are for other Spanish conquistadors. Tourism agencies have informational webpages about Estebanico’s past, but there are no tourism sites around his historic journeys. (more)

How ‘Strange Fruit’ Killed Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday and Mister at Downbeat in New York City, ca. Feb. 1947. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

(Progressive.org) “Strange Fruit” may have been written by American song-writer and poet Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. Lewis Allen), but ever since Billie Holiday sang the three brief stanzas to music in 1937, she’s owned it. Jazz writer Leonard Feather referred to the song as “the first significant protest in words and music, the first significant cry against racism.”

The song’s lyrics were shocking to some members of Holiday’s mostly white audiences:

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

At times, her performance of the song was met with fierce pushback. In the end, Billie Holiday’s insistence on performing “Strange Fruit” may have been responsible for her demise. (more)

Related: (Timeline) “How a racist hate-monger masterminded America’s War on Drugs.” Harry Anslinger conflated drug use, race, and music to criminalize non-whiteness and create a prison-industrial complex. (read)

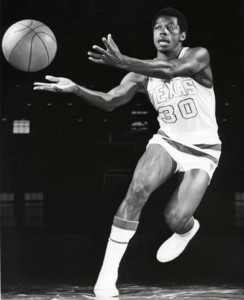

Black History Month at Texas: Remembering three Longhorns sports pioneers

Former UT basketball player Jimmy Blacklock helped integrate the school’s basketball program. He’s now a coach for the Harlem Globetrotters. (University of Texas)

On Jan. 4, 2006, on a fourth-and-5 at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif., Vince Young ran into the end zone and Longhorns lore.

Young’s touchdown that won the national championship is perhaps the most famous play in the history of UT sports. It also was just one of many athletic achievements attributed to a black athlete at Texas.

The jerseys of Kevin Durant and T.J. Ford have ascended to the rafters at the Erwin Center. Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams have won the school’s only Heisman Trophies. Carlette Guidry and Sanya Richards-Ross have earned multiple Olympics gold medals.

Black athletes have accomplished a lot at Texas in a relatively short time. In 1964, former track and field athlete James Means Jr. integrated the athletic department that has existed since the late 1800s after his mother, activist Bertha Means, pressured UT regent Frank Erwin for his inclusion. Six years later, Julius Whittier became the first black letterman on the football team.

As Black History Month nears its end, here are some stories of several UT pioneers.

(more)

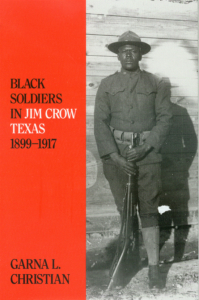

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Black Soldiers in Jim Crow Texas, 1899-1917,” by Garna Christian.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Black Soldiers in Jim Crow Texas, 1899-1917,” by Garna Christian.

In Jim Crow Texas, black Regular Army units returning victoriously from Cuba and the Philippines collided head-on with local segregation and bigotry. As the soldiers’ expectations of dignity and respect met with racial restrictions and indignities from civilian communities, a series of violent episodes erupted.

Although confrontations also occurred elsewhere, the most notorious were in Texas, beginning with an 1899 clash between white lawmen in Texarkana and black soldiers riding a troop train west after returning from Cuba. The first truly violent episode came in 1906, when troops were accused of attacking Brownsville after civilian provocations. In 1917 a full-scale battle in Houston resulted in fifteen dead and twenty-one injured. Between 1899 and 1917, a series of other face-offs—some involving the complex relationships of blacks with local Hispanic populations—occurred when black soldiers stood up for their rights or their lives in San Antonio, Laredo, El Paso, Rio Grande City, Del Rio, and Waco.

This little-known story, never before told in full, illuminates the collision of racial discrimination with racial pride and reveals once again the petty biases, institutionalized racism, and mutual suspicions that have divided American society. But it is also a story of lofty aspirations too long delayed, of the transformation of a downtrodden race into a self-confident people, and of the noble attempt, however dangerous its means, to realize full citizenship.

Clearly written and impressively researched, Black Soldiers in Jim Crow Texas traces the relationship of the four black military regiments—the 24th and 25th Infantries and the 9th and 10th Cavalries—with white civilian communities in the period between the Spanish-American War and World War I. Drawn from previously unexploited sources, it fills a void in the increasing body of research on the black military and illuminates the magnitude of racial intolerance in early twentieth-century America. No other work has explored these issues in such depth and with such skill.

This Week in Texas Black History

Feb 26

Heman Sweatt, accompanied by a delegation from the NAACP, met with University of Texas president Theophilus S. Painter and other university officials on this day in 1946 to present a formal request for Sweatt’s admission to the UT law school. The legal case resulting from this request, Sweatt v. Painter, became a landmark civil rights decision, one of several that struck down the doctrine of “separate but equal” educational facilities. Sweatt finally registered at the school on September 19, 1950.

Feb 27

Negro Leagues pitcher Hilton Smith was born on this day in 1907 in Giddings. He played baseball at Prairie View A&M College and then, in 1931 with the Austin Black Senators and in 1932 the Monroe (La.) Monarchs. In 1937, he joined the Kansas City Monarchs, of the newly formed Negro American League and played there until 1948. With Kansas City, he frequently came on in relief of the great Satchel Paige. Smith was named to six consecutive East-West All-star Games (’37-42) and won 20 or more games in each of his 12 seasons with Kansas City, including a 93-11 record over a four-year span (’39-42). He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001. Buck O’Neil, his teammate and close friend said of him, “From 1940 to 1946, Hilton Smith might have been the greatest pitcher in the world.”

r 19, 1950.

Feb 28

On this date in 1945, All-Pro defensive end Charles “Bubba” Smith was born in Orange. Smith played for his father, Willie Ray Smith, at Beaumont Charlton-Pollard HS and attended Michigan State University where he was a two-time All-American defensive end. Smith was the first pick of the 1967 NFL draft by the Baltimore Colts, and was a member of their Super Bowl V winning team. During his nine-year career, he also played with the Oakland Raiders and the Houston Oilers. After football, Smith became an actor, most noted for his roles in six “Police Academy” films. In 1988, he was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame.

Mar 3

On this date in 1865, the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill was passed by the U.S. Congress. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was a branch of the U.S. Army created to provide practical aid to 4,000,000 newly freed Black Americans in their transition from slavery to freedom. The agency also helped whites left homeless by the Civil War. The Freedmen’s Bureau operated in Texas from late September 1865 until July 1870.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Latest Entries

A New Hope

Forgive me for borrowing the title of one of the most profitable films in history, “Star Wars: A New Hope.” I’ve always been enamored by space. I’m a child of the 1960s and I [...]

Tell me the truth

Democracy – a) government by the people, b) a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them, directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving [...]

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.