Black Women, Agency, and the Civil War

By Karen Cook Bell

Lucy Higgs with her daughter Mona escaping slavery from Grays Creek, Tennessee to the Union lines, June of 1862. (Credit: Kathy Grant, artist)

(Black Perspectives) Throughout much of the twentieth century historians framed the Civil War as a political and military driven historical process, which largely involved and impacted men. Within the academy, social and cultural historians have now shifted the focus of the Civil War away from military battles to what the war meant for soldiers, white women and enslaved men and women. The Civil War has constituted an important pillar of dialogue and debate over the meaning of freedom, free labor, and citizenship. In his seminal study Black Reconstruction in America, W.E.B. DuBois argued that “the Civil War meant emancipation and the black worker won the war by a general strike which transferred his labor to the Northern invader in whose army lines workers began to be organized as a new labor force.” DuBois’s emphasis on the “agency” of slaves set the terms of the debate in modern scholarship, which continues to emphasize the agency of enslaved men and women. DuBois also ushered in a period of new scholarship, which wrote against the silences and omissions of the U.S. historical profession.

Emphasizing the agency of soldiers and civilians has led to diverse perspectives over the process of wartime emancipation and its impact on the agency of former slaves. Within this frame, the experience of black women has emerged as a distinctive area of scholarly inquiry. The centrality of black women to our understanding of experience and identity has taught scholars much about the deep and complex connections between the personal and the political. As Darlene Clark Hine has observed, as members of two subordinate groups in American society, African American women often fell between the cracks of Black history and women’s history. Yet, African American women played essential roles in ensuring the survival of black people during slavery and of black communities in freedom. In slavery and freedom, black women established women centered networks to serve the needs of the black community. (more)

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments, please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.

A man runs from a line of charging police in riot gear in Baltimore. The photo, taken by Devin Allen, is featured in the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s newest exhibit, “More Than A Picture.”

(NPR) Remembering our nation’s history through photographs is the focus of the newest and first special exhibition at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“More Than A Picture” features more than 150 images from 80 well-known and lesser-known photographers who documented the lives of African-Americans. Their works showcase subjects who, in ordinary and extraordinary moments, shaped history.

One of the oldest photos – of an enslaved family – is estimated to have been taken between 1861 and 1862 on a plantation in Virginia. There is a photograph of the abolitionist Sojourner Truth, a well-known image of Black Panther leader Kathleen Cleaver clutching a rifle and a candid shot of author-activist James Baldwin being admired by a group of sailors in Turkey.

And, alongside the now-familiar photos of civil rights marches in the 1960s, the exhibit includes digital prints from recent protests in 2015.

Curator Aaron Bryant says it was important to integrate the older, iconic civil rights photos with those taken in the past few years, in Ferguson, Mo., and Baltimore.

“We wanted to help people to understand that history isn’t just in these objects that you would buy in an antique store, or at an auction like Sotheby’s or Christie’s,” Bryant says. “History is about everyday people and everyday lives. And you can find important significant cultural as well as historical objects right there in your home.” (more)

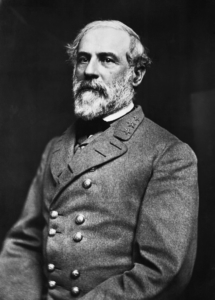

To Be Black at Robert E. Lee High School

The school board in Tyler, a small town in East Texas, recently met to debate whether to rename Robert E. Lee high school, which is now almost sixty per cent black and Latino. Photograph by Bettmann / Getty

(The New Yorker) Last spring in Tyler, Texas, a small city two hours east of Dallas, an African-American couple had a series of agonizing conversations at their kitchen table at night, talking softly after their children were in bed. Their daughter, and oldest child, loved cheerleading in junior high; she was eager to try out for the squad at the local public high school, where she was set to enroll as a freshman in the fall. But the name of this particular school in Tyler, a community that some residents like to think of as the western edge of the Old South, ate away at her parents. “We would ask ourselves, Are we really gonna have our daughter running around a football field yelling, ‘I love Robert E. Lee’?” the mother told me.

“No one should have to go to a school named for their oppressor.”

On a humid Monday evening last month, she was one of nearly three hundred parents and residents who showed up for a school-board meeting to join-or rejoin-a half-century-old fight in Tyler: What to do with Robert E. Lee High School? Those who support changing the name contend that the time is right, given the school’s current demographics and the fact that it is being torn down and completely rebuilt in a hundred-and-twenty-two-million-dollar renovation. Opponents say changing the name would erase history. (more)

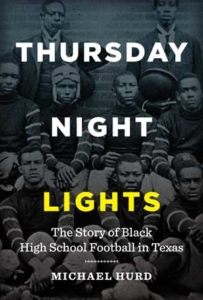

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Thursday Night Lights, The Story of Black High School Football in Texas,” by Michael Hurd.

At a time when “Friday night lights” shone only on white high school football games, African American teams across Texas burned up the gridiron on Wednesday and Thursday nights. The segregated high schools in the Prairie View Interscholastic League (the African American counterpart of the University Interscholastic League, which excluded black schools from membership until 1967) created an exciting brand of football that produced hundreds of outstanding players, many of whom became college All-Americans, All-Pros, and Pro Football Hall of Famers, including NFL greats such as “Mean” Joe Green (Temple Dunbar), Otis Taylor (Houston Worthing), Dick “Night Train” Lane (Austin Anderson), Ken Houston (Lufkin Dunbar), and Bubba Smith (Beaumont Charlton-Pollard).

Thursday Night Lights tells the inspiring, largely unknown story of African American high school football in Texas. Drawing on interviews, newspaper stories, and memorabilia, Michael Hurd introduces the players, coaches, schools, and towns where African Americans built powerhouse football programs under the PVIL leadership. He covers fifty years (1920–1970) of high school football history, including championship seasons and legendary rivalries such as the annual Turkey Day Classic game between Houston schools Jack Yates and Phillis Wheatley, which drew standing-room-only crowds of up to 40,000, making it the largest prep sports event in postwar America. In telling this story, Hurd explains why the PVIL was necessary, traces its development, and shows how football offered a potent source of pride and ambition in the black community, helping black kids succeed both athletically and educationally in a racist society.

This Week in Texas Black History, Sep. 24-30

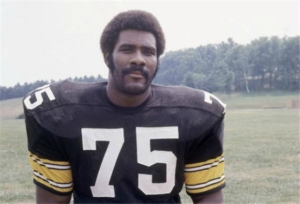

Charles Edward Greene

Sep24

On this day in 1946, football great Charles Edward Greene, “Mean Joe”, was born in Temple, Texas. Greene starred at Dunbar High School, then became an All-American lineman in 1968 at North Texas State University. Greene (6-4, 275 pounds) was the Pittsburgh Steelers No. 1 pick in the 1969 National Football League draft and was a dominant force on the Steelers’ four Super Bowl championship teams the 1970s as leader of their “Steel Curtain” defense. He was NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year in 1969, played in 10 Pro Bowls, was All-NFL five times, and NFL Defensive Player of the Year in 1972 and 1974. He was inducted to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1987.

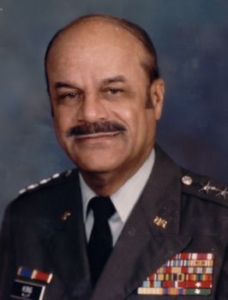

John Quill Taylor King

Sep25

John Quill Taylor King was born on this day in 1921, in Memphis, Tenn. King attended L.C. Anderson High School in Austin, graduating at age 15, and received a mathematics degree from Fisk University and a Ph.D. in mathematics and statistics from UT-Austin in 1957. King was a faculty member at Huston-Tillotson University and rose to become the school’s dean and then president in 1965 and chancellor in 1987. He entered the U.S. Army during WWII as a private, but earned officer status and retired as a major general in 1983. Upon leaving active duty, King became the Army Reserves’ first black general officer. With the Texas State Guard, he was promoted to Lt. Gen. in 1985. His mother, Alice Clinton Woodson, was a direct descendant of Thomas Woodson, son of slave Sally Hemings and her owner, Thomas Jefferson. A licensed mortician, King was also president of King-Tears Mortuary, Inc. in Austin.

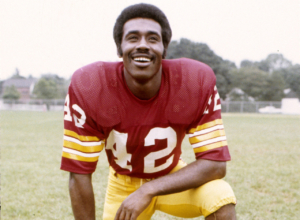

Charley Taylor

Sep28

On this day in 1941, Charley Taylor, was born in Grand Prairie, Texas. A multi-sport star at Dalworth High School, Taylor was all-state in football and track. At Arizona State University, he was an All-American in football (running back and defensive back), but also excelled in baseball. Taylor was the third overall pick in the 1964 NFL draft by the Washington Redskins and was named National Football Conference Rookie of the Year as a running back. He was switched to wide receiver two seasons later and led the league in receiving three times. He retired after the 1977 season as the NFL’s all-time leading receiver with 649 catches for 9,110 yards and 79 touchdowns. He was inducted to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1984.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Latest Entries

A New Hope

Forgive me for borrowing the title of one of the most profitable films in history, “Star Wars: A New Hope.” I’ve always been enamored by space. I’m a child of the 1960s and I remember playing with my Major Matt Mason action figure (not a doll!) as my family and I watched Neil Armstrong step onto the moon and state “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” in 1969. I still [...]

Tell me the truth

Democracy – a) government by the people, b) a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them, directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections. Merriam-Webster Dictionary There were many things I learned from my father. He taught me how to change the oil in my car, paint a house, and even how to get the pretty girl at a party. [...]

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.