Staring Down Development, Neighbors Seek Historical Recognition for Austin’s Emancipation Park

(Photo: Thomas J. White and members of the Emancipation Association. Credit: Austin History Center)

Our story begins at a dead end near 13th Street and Walnut Avenue in the Chestnut neighborhood of East Austin, just down the street from where Leslie Padilla has lived for about three years.

You wouldn’t know it from looking at it, but a vacant field just past this dead end is a piece of Austin’s African-American history. About a century ago, this land was home to the city’s annual Juneteenth celebration, which marks the end of slavery in Texas.

Padilla learned about the site’s history when a new condo development was proposed for the land. She and other neighbors have been negotiating with the developer to recognize the historical significance of the site, among other considerations.

Austin’s earliest Juneteenth celebrations were held at Wheeler’s Grove, which is now know as Eastwoods Park near the UT campus. But some decades later, Thomas J. White, a former slave, thought Juneteenth should be held on land owned by black residents themselves. He founded the Emancipation Park Association in 1905, and two years later, it completed the purchase of a 5-acre tract near Rosewood Avenue and Chicon Street. (read more, hear broadcast, see video)

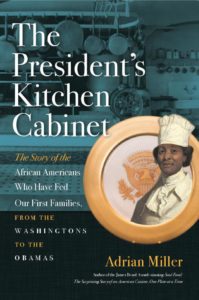

Literary: “The President’s Kitchen Cabinet”

Our national palate owes a vast debt to African-American cooks and chefs who’ve largely been whitewashed from the history books, but a growing number of scholars, bloggers and authors are bringing new attention to those hidden hands.

Our national palate owes a vast debt to African-American cooks and chefs who’ve largely been whitewashed from the history books, but a growing number of scholars, bloggers and authors are bringing new attention to those hidden hands.

Adrian Miller, author of the new book The President’s Kitchen Cabinet, dissects the social and political considerations that saw African-American contributions minimized or outright ignored as they fed the First Family, from George Washington to our first black president, Barack Obama.

“Black hands — enslaved and free — wove the fabric of social life in the nation’s capital, and black people, widely considered by whites as inherently bred for servitude, were integral to cementing a white family’s social status as an elite household. Our presidential families were no exception,” Miller writes. “Many presidents went out of their way to reassure the public that they loved the homey dishes prepared by their African-American cooks, though they rarely dignified these cooks by referring to them by their full names.”

For hundreds of years, slave-owning white families depended upon African-Americans to grow, prepare and serve their food. Washington himself brought slaves to the executive kitchen (he was the only president to not live in the White House, as he died before the federal government formally moved from Philadelphia) and complained bitterly when his cook ran away after a decade of servitude. Washington spent a year trying to track down Hercules, also known as Uncle Harkless, referring in a letter to a friend about the “inconvenience” his family suffered at his slave’s freedom. (read more)

Black Cowboys, Busting One of America’s Defining Myths

In a 2016 portrait by the photographer Brad Trent, an older black woman poses on a bale of hay, a white Stetson hat on her head and a pair of hand-tooled cowboy boots on her feet. The fringe on her leather jacket flows downward, as do her knee-length dreadlocks, which echo the texture of the lasso coiled in her fist. Her posture is at once relaxed and confrontational. Her gaze is steely as a gun.

In a 2016 portrait by the photographer Brad Trent, an older black woman poses on a bale of hay, a white Stetson hat on her head and a pair of hand-tooled cowboy boots on her feet. The fringe on her leather jacket flows downward, as do her knee-length dreadlocks, which echo the texture of the lasso coiled in her fist. Her posture is at once relaxed and confrontational. Her gaze is steely as a gun.

The woman in the image is Kesha (Mama) Morse, the sixty-seven-year-old president of the New York Federation of Black Cowboys, an organization that is devoted to teaching inner-city kids about a neglected aspect of American history: the thousands of African-Americans who played a role in settling the Old West. According to scholars, one in four cowboys working in Texas during the golden age of westward expansion was black; many others were Mexican, mestizo, or Native American—a far more diverse group than Hollywood stereotypes of the cowboy would suggest. Bass Reeves, a black lawman who had a Native American sidekick, is thought to have served as a model for the Lone Ranger. Britt Johnson, a black cowboy whose wife and children were captured by Comanches, in 1865, partly inspired John Ford’s classic film “The Searchers,” almost a century later. In the wake of the Civil War, the African-American Buffalo Soldiers were dispatched by Congress to protect Western settlers and federal land.

Morse’s portrait, which Trent shot last year for the Village Voice, appears alongside the work of other photographers in a compact but exciting new exhibit, “Black Cowboy,” at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The photos, like the very idea of a black cowboy, suggest that that many common conceptions of what an iconic American looks like are wrong. (read more)

Stories of Sports Champions in the African American History Museum Prove the Goal Posts Were Set Higher

The sports exhibition delves into the lost, forgotten or denied history of the heroes on the field

Former presidential candidate and civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson was thoughtful last fall as he strolled through the exhibition “Sports: Leveling the Playing Field” during the opening days of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Headgear worn by boxing legend Muhammad Ali at the 5th Street Gym in Miami during the 1960s caught his attention.

Former presidential candidate and civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson was thoughtful last fall as he strolled through the exhibition “Sports: Leveling the Playing Field” during the opening days of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Headgear worn by boxing legend Muhammad Ali at the 5th Street Gym in Miami during the 1960s caught his attention.

“I have to take some time to process it all. I knew Ali, particularly when he was out of the ring, when he was left in the abyss. I was there the night he came back into the ring,” Jackson says, referring to the four years during the Vietnam War when Ali was stripped of his heavyweight titles for draft evasion, and before his conviction was overturned in 1971 by the Supreme Court.

Jackson is walking by 17 displays called the “Game Changers” cases that line the hallway in symmetrical splendor. Inside each is a wealth of pictures and artifacts belonging to some of the greatest athletes in our nation’s history—from tennis star Althea Gibson, the first African-American to play in the U.S. National Championships, to pioneer Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in baseball.

“What’s touching me is I preached at Joe Louis’ funeral. . . . I was the eulogist for Jackie Robinson in New York . . . I was the eulogist for Sugar Ray Robinson,” Jackson says. “I was there when Dr. King was killed in 1968. I wept. I was there when Barack Obama was determined to be the next President and I wept. From the balcony in Memphis to the balcony at the White House was 40 years of wilderness. . . . So to be here with people who made such a great impact, all these things in the wilderness period made us stronger and more determined.” (read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

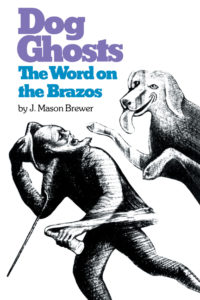

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Dog Ghosts and the Word On the Brazos,” by J. Mason Brewer.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Dog Ghosts and the Word On the Brazos,” by J. Mason Brewer.

This book contains two volumes of African American folk tales collected by J. Mason Brewer.

The stories included in Dog Ghosts are as varied as the Texas landscape, as full of contrasts as Texas weather. Among them are tales that have their roots deeply imbedded in African, Irish, and Welsh mythology; others have parallels in pre-Columbian Mexican tradition, and a few have versions that can be traced back to Chaucer’s England. All make delightful reading. The title Dog Ghosts is drawn from the unique stories of dog spirits which Dr. Brewer collected in the Red River bottoms and elsewhere in Texas.

The Word On the Brazos is a delightful collection of “preacher tales” from the Brazos River bottom in Texas. J. Mason Brewer worked side by side with field hands in the Brazos bottoms; he lived in their homes, worshipped in their churches, and shared the moments of relaxation in which laughter held full sway.

Many of the tales these people told were related to religion—both “good religion” and “bad religion.” Some of them concerned preachers and their families, while others were stories told in pulpits. Mr. Brewer has set all of these stories down in authentic yet easily readable dialect. They will delight all who are interested in the historic culture of rural African-American Texans, as well as those who simply enjoy fine humorous stories skillfully told.

This Week In Texas Black History, Jan. 22-28

22 – On this day in 1926, Dr. Herman A. Barnett, III was born in Austin. In 1950, he became the first black student at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. In the previous year, Barnett had been accepted to the school but as a student in Houston at Texas State University for Negroes (Texas Southern University) attending UTMB under a contract program between the schools. The program was stopped after the Veterans Administration (Barnett’s tuition was covered by the GI Bill) refused to recognize the contract system and Barnett’s attorney threatened legal action. Barnett became a prominent surgeon and anesthesiologist and was a graduate of Huston College in Austin. During WWII, he was a Tuskegee Airman (332nd Fighter Group) and in 1968 became the first African-American to serve on the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners. In 1973, Barnett was the first black elected president of the Board of Trustees of the Houston Independent School District.

22 – On this day in 1926, Dr. Herman A. Barnett, III was born in Austin. In 1950, he became the first black student at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. In the previous year, Barnett had been accepted to the school but as a student in Houston at Texas State University for Negroes (Texas Southern University) attending UTMB under a contract program between the schools. The program was stopped after the Veterans Administration (Barnett’s tuition was covered by the GI Bill) refused to recognize the contract system and Barnett’s attorney threatened legal action. Barnett became a prominent surgeon and anesthesiologist and was a graduate of Huston College in Austin. During WWII, he was a Tuskegee Airman (332nd Fighter Group) and in 1968 became the first African-American to serve on the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners. In 1973, Barnett was the first black elected president of the Board of Trustees of the Houston Independent School District.

22 — Blues and gospel singer Blind Willie Johnson was born on this day in 1897 in Independence, Texas. While Jan. 22 is the date noted on his death certificate, other accounts list his birth on December 6, 1902 near Temple, Texas. Johnson recorded 30 songs, including his most popular, “Dark Was the Night — Cold Was the Ground,” a song about the crucifixion of Jesus.

22 — Blues and gospel singer Blind Willie Johnson was born on this day in 1897 in Independence, Texas. While Jan. 22 is the date noted on his death certificate, other accounts list his birth on December 6, 1902 near Temple, Texas. Johnson recorded 30 songs, including his most popular, “Dark Was the Night — Cold Was the Ground,” a song about the crucifixion of Jesus.

23 — John Saunders Chase, Jr. was born on this day in 1925 in Annapolis, Md. On June 7, 1950, when Chase enrolled at the University of Texas, the school became the first major university in the South to enroll an African-American. Chase earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first African-American graduate of the university. That same year, Chase became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade.

23 — John Saunders Chase, Jr. was born on this day in 1925 in Annapolis, Md. On June 7, 1950, when Chase enrolled at the University of Texas, the school became the first major university in the South to enroll an African-American. Chase earned a Master of Architecture degree in 1952 and became the first African-American graduate of the university. That same year, Chase became the first licensed African-American architect in Texas and was the only black architect licensed in the state for almost a decade.

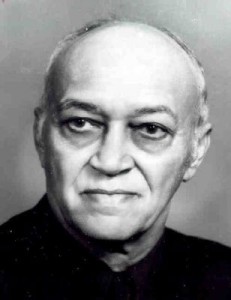

24 – On this date in 1975, J. Mason Brewer died. Brewer, considered the premier African-American folklorist of the twentieth century, was born in Goliad in 1896 and became the first author and speaker to use black American dialect extensively in front of and to all audiences, particularly when dealing with folklore. He was the first black member of both the Texas Folklore Society and the Texas Institute of Letters. His most noted works include “Aunt Dicy Tales,” and an anthology, “American Negro Folklore,” for which he won the Chicago Book Fair Award in 1968.

24 – On this date in 1975, J. Mason Brewer died. Brewer, considered the premier African-American folklorist of the twentieth century, was born in Goliad in 1896 and became the first author and speaker to use black American dialect extensively in front of and to all audiences, particularly when dealing with folklore. He was the first black member of both the Texas Folklore Society and the Texas Institute of Letters. His most noted works include “Aunt Dicy Tales,” and an anthology, “American Negro Folklore,” for which he won the Chicago Book Fair Award in 1968.

25 – On this day in 1915, Independence Heights became the first incorporated black city in Texas. Located northeast of Houston, it had a population of 600 and G.O. Burgess was its mayor. The area was annexed to Houston on December 26, 1929.

26 – Bessie Coleman was born on this date in 1892 in Atlanta, Texas. Thwarted by racism in her quest to become a pilot, Coleman eventually went to France to train and in 1921 became the first licensed black pilot in the world. As a stunt pilot, she became known as “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie” in 1995 the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bessie’s honor and in 2000 was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. The main road to Atlanta’s airport is named Bessie Coleman Drive. (Video: “Bessie Coleman, An American Hero“)

26 – Bessie Coleman was born on this date in 1892 in Atlanta, Texas. Thwarted by racism in her quest to become a pilot, Coleman eventually went to France to train and in 1921 became the first licensed black pilot in the world. As a stunt pilot, she became known as “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie” in 1995 the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in Bessie’s honor and in 2000 was inducted into the Texas Aviation Hall of Fame. The main road to Atlanta’s airport is named Bessie Coleman Drive. (Video: “Bessie Coleman, An American Hero“)

26 – On this date in 1980, former L.C. Anderson High School band leader B.L. Joyce died in San Jose, California. Joyce was born in the late 1800s in Plaquemine, La. He attended Samuel Huston College in Austin before becoming band director at Anderson High School, from 1934 to 1955. Under his leadership, the band won the state championship seven times between 1940 and 1953 at the Prairie View Interscholastic League competitions. Among his many star pupils was noted jazz trumpeter Kenny Dorham.

26 – On this date in 1980, former L.C. Anderson High School band leader B.L. Joyce died in San Jose, California. Joyce was born in the late 1800s in Plaquemine, La. He attended Samuel Huston College in Austin before becoming band director at Anderson High School, from 1934 to 1955. Under his leadership, the band won the state championship seven times between 1940 and 1953 at the Prairie View Interscholastic League competitions. Among his many star pupils was noted jazz trumpeter Kenny Dorham.

26 – On this date in 1970, contemporary gospel musician and producer Kirk Franklin was born in Fort Worth. A multi-Grammy Award winner, Franklin learned to play piano as an infant and by age 11 was leading the Mt. Rose Baptist Church adult choir in Dallas. His first album, 1993’s “Kirk Franklin & the Family,” spent 100 weeks on the gospel charts (several times as No. 1), crossed over to the R&B charts, and became the first gospel debut album to go platinum.

26 – On this date in 1970, contemporary gospel musician and producer Kirk Franklin was born in Fort Worth. A multi-Grammy Award winner, Franklin learned to play piano as an infant and by age 11 was leading the Mt. Rose Baptist Church adult choir in Dallas. His first album, 1993’s “Kirk Franklin & the Family,” spent 100 weeks on the gospel charts (several times as No. 1), crossed over to the R&B charts, and became the first gospel debut album to go platinum.

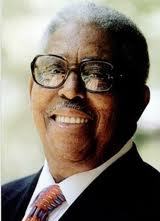

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Misc. musings,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.