Austin Businesswoman Helps Bring a Slice of African-American History to UT Austin’s Blanton Museum

When the Blanton unveils its reinstalled permanent collection in February, a 10-foot-tall, three-dimensional portrait made of 3,840 hair combs is sure to capture visitors’ attention.

The portrait depicts Madam C.J. Walker, an African-American entrepreneur who’s often called the first self-made female millionaire in U.S. history.

The new acquisition will be the first in the museum’s collection depicting a female African-American historical figure, and was funded by a grassroots effort led by a local African-American businesswoman named Marilyn Johnson. The majority of that fundraising, Johnson says, was raised from the black professional community in Austin over a four-year period. The museum is purchasing the piece for $72,000 – all but $3,000 of which has been paid off.

The artist, Sonya Clark, is African American and has pieces in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as well as in the Indianapolis Museum of Art. She will be at the Blanton to discuss her sculpture on Feb. 16 at an event that is free and open to the public. Madam C.J. Walker will be unveiled along with the rest of the Blanton’s reinstalled permanent collection on the Feb. 12. (read more, listen to interview with Ms. Johnson)

African-American History On View in Texarkana

Two winter exhibits at the Texarkana Regional Arts and Humanities Center are well timed to celebrate African-American History Month in February. From January 28 to March 16, the museum showcases “For All the World To See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights.” And for four and a half weeks, January 31 to March 4, the center hosts its 14th annual Regional Celebration of African-American Artists Exhibit: Local Artists and Collectors, featuring works by two local artists.

Two winter exhibits at the Texarkana Regional Arts and Humanities Center are well timed to celebrate African-American History Month in February. From January 28 to March 16, the museum showcases “For All the World To See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights.” And for four and a half weeks, January 31 to March 4, the center hosts its 14th annual Regional Celebration of African-American Artists Exhibit: Local Artists and Collectors, featuring works by two local artists.

The first exhibition examines the influence of visual culture and images that shaped and transformed the struggle for racial equality in America, paying particular attention to the realities of segregation and racial violence as well the inspiration for activism, African-American pride and the Black Power movement.

Sponsored by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and others, the exhibit includes 250 objects — posters, photographs, television and radio clips, political buttons, comic books and toys — that track the development of the civil rights movement from the 1940s to the 1970s. (read more)

Collard greens and black-eyed peas: The history of why we eat them on New Year’s

All across the globe, people eat special dishes or toast celebratory flutes of Champagne to ring in the New Year, hoping to usher in luck and positive energy in the year to come.

All across the globe, people eat special dishes or toast celebratory flutes of Champagne to ring in the New Year, hoping to usher in luck and positive energy in the year to come.

While Filipinos are chowing down on long noodles for a long life and Spaniards are popping 12 grapes in their mouths at midnight, some Americans will sit down to a steamy plate of collard greens and black-eyed peas. But why has eating this Southern dish become a New Year’s tradition?

Legend has it that collard greens and black-eyed peas are said to represent a prosperous new year, with the greens symbolizing cash and peas coins. American currency, however, is nothing like the dark green hue of cooked collards and at no point have we used puny, white pea-sized balls as change. While some may still eat collards and peas for this reason to ring in the new year, the tradition dates hundreds of years back in American history and even further back across the Atlantic.

Black-eyed peas were cultivated in Africa over 5,000 years ago, historian Jessica B. Harris explained in her New York Times op-ed, “Prosperity Starts with a Pea,” in December 2010. In the 1700s, black-eyed peas, exported during the transatlantic slave trade, were planted in the Carolinas and “eaten by enslaved Africans and poorer whites,” Harris wrote. And the foods eaten by slaves eventually moved their way up to the master’s table, where black-eyed peas became a staple ingredient in the dish Hoppin’ John, made with black-eyed peas, rice and pork. (read more)

Black History In brief

January 3, 1624: The first African-American birth was recorded. William Tucker, the first African-American child born in the American colonies, was baptized in Jamestown, Virginia.

January 5, 1804: Two years after outlawing slavery, Ohio became the first Northern state to pass “Black Codes,” or legislation curbing the rights of African Americans. By 1860, they lost more liberties than they had enjoyed following the Revolutionary War.

January 7, 1891: Noted author of the Harlem Renaissance, Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama, whose father later became mayor of Eatonville, Florida — one of the few incorporated all-black towns in the U.S. She wrote four novels and dozens of short stories and essays. She is best known for her 1937 novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. That same year, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship to conduct research on those who lived in Jamaica and Haiti.

January 4, 1923: Hundreds of white men began burning Rosewood, Florida. Within three days, the entire African-American town had been burned to the ground. By the time the violence ended, six African Americans and two whites had died, according to the official count. Michael D’Orso’s book, Like Judgment Day, tells the story of what happened, including the Florida Legislature voting in 1994 to compensate victims and their families. Three years later, Hollywood released a movie on the event, Rosewood.

January 7, 1955: Marian Anderson became the first African American to sing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. The event came 16 years after the Daughters of the American Revolution turned her away from a 1939 performance in Constitution Hall. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who had resigned as a result, invited Anderson to sing in front of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday. In a nationwide radio broadcast, millions heard her sing “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” DAR reversed its position and invited her to perform many more times.

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Negro and His Folklore in Nineteenth-Century Periodicals,” edited by Bruce Jackson.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “The Negro and His Folklore in Nineteenth-Century Periodicals,” edited by Bruce Jackson.

In the eyes of many white Americans, North and South, the Negro did not have a culture until the Emancipation Proclamation. With few exceptions, serious collecting of Negro folklore by whites did not begin until the Civil War—and it was to be another four decades before black Americans would begin to appreciate their own cultural heritage. Few of the earlier writers realized that they had observed and recorded not simply a manifestation of a particular way of life but also a product peculiarly American and specifically Negro, a synthesis of African and American styles and traditions.

The folksongs, speech, beliefs, customs, and tales of the American Negro are discussed in this anthology, originally published in 1967, of thirty-five articles, letters, and reviews from nineteenth-century periodicals. Published between 1838 and 1900 and written by authors who range from ardent abolitionist to dedicated slaveholder, these articles reflect the authors’ knowledge of, and attitudes toward, the Negro and his folklore. From the vast body of material that appeared on this subject during the nineteenth century, editor Bruce Jackson has culled fresh articles that are basic folklore and represent a wide range of material and attitudes. In addition to his introduction to the volume, Jackson has prefaced each article with a commentary. He has also supplied a supplemental bibliography on Negro folklore.

If serious collecting of Negro folklore had begun by the middle of the nineteenth century, so had exploitation of its various aspects, particularly Negro songs. By 1850 minstrelsy was a big business. Although Jackson has considered minstrelsy outside the scope of this collection, he has included several discussions of it to suggest some aspects of its peculiar relation to the traditional. The articles in the anthology—some by such well-known figures as Joel Chandler Harris, George Washington Cable, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, John Mason Brown, and Antonin Dvorak—make fascinating reading for an observer of the American scene. This additional insight into the habits of thought and behavior of a culture in transition—folklore recorded in its own context—cannot but afford the thinking reader further understanding of the turbulent race problems of later times and today.

This Week In Texas Black History, Jan. 1-7

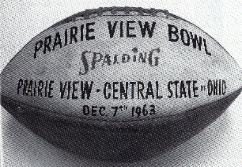

1 – On this day in 1929 the first black college football bowl game was played. The Prairie View Bowl was initially played at Houston’s West End Park, located in the Freedman’s Town area of Fourth Ward and later at Jeppesen Stadium, the Houston Independent School District’s public stadium, in Third Ward. With the exception of four games, the bowl game was played annually until 1963 on Jan. 1.

1 – On this day in 1929 the first black college football bowl game was played. The Prairie View Bowl was initially played at Houston’s West End Park, located in the Freedman’s Town area of Fourth Ward and later at Jeppesen Stadium, the Houston Independent School District’s public stadium, in Third Ward. With the exception of four games, the bowl game was played annually until 1963 on Jan. 1.

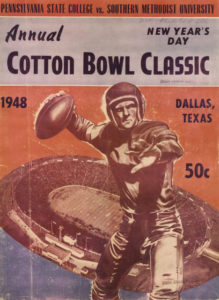

1 – The 1948 Cotton Bowl football game in Dallas featured the first African Americans to participate in the game when Southern Methodist and Penn State played to a 13-13 tie. Penn State’s roster included running back Wally Tripplett and wide receiver Dennie Hoggard. It was the first interracial game played at the stadium.

1 – The 1948 Cotton Bowl football game in Dallas featured the first African Americans to participate in the game when Southern Methodist and Penn State played to a 13-13 tie. Penn State’s roster included running back Wally Tripplett and wide receiver Dennie Hoggard. It was the first interracial game played at the stadium.

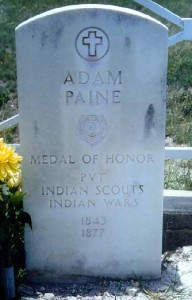

1 – Adam (“Adan”) Paine, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient, died on this day in 1877. Paine was a scout at Fort Duncan, Texas and received the MOH for his actions during a battle at Quitaque Peak where he defended himself and four other scouts against several bands of Comanche Indians on September 26, 1874. Thanks to his efforts during the engagement, all of the scouts survived. Paine’s commanding officer, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, said that Paine “has more cool (and) daring than any scout I have ever known.”

1 – Adam (“Adan”) Paine, a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient, died on this day in 1877. Paine was a scout at Fort Duncan, Texas and received the MOH for his actions during a battle at Quitaque Peak where he defended himself and four other scouts against several bands of Comanche Indians on September 26, 1874. Thanks to his efforts during the engagement, all of the scouts survived. Paine’s commanding officer, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, said that Paine “has more cool (and) daring than any scout I have ever known.”

![Fatburger Logo [/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=](https://www.pvamu.edu/tiphc/wp-content/uploads/sites/107/2016/01/Fatburger-Logo-F1-300x247.jpg) 3 – On this day in 1912, the founder of the Fatburger restaurant chain, Lovie Louise Yancey, was born in Bastrop. She moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1940s and at age 35 partnered with Charles Simpson to open their first restaurant, a three-stool hamburger stand in South Central Los Angeles in 1947. They called the business Mr. Fatburger, dropping the “Mr.” in 1952. By the end of 1985, the chain had over fifteen franchise sites throughout southern California. Noted as “The Last Great Hamburger Stand,” Fatburger now has restaurants in 29 countries, including China, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates. Yancey established a $1.7-million endowment at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California in 1986 for research into sickle-cell anemia as a dedication to her grandson who died of the disease. Yancey died of pneumonia on January 26, 2008, at the age of 96.

3 – On this day in 1912, the founder of the Fatburger restaurant chain, Lovie Louise Yancey, was born in Bastrop. She moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1940s and at age 35 partnered with Charles Simpson to open their first restaurant, a three-stool hamburger stand in South Central Los Angeles in 1947. They called the business Mr. Fatburger, dropping the “Mr.” in 1952. By the end of 1985, the chain had over fifteen franchise sites throughout southern California. Noted as “The Last Great Hamburger Stand,” Fatburger now has restaurants in 29 countries, including China, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates. Yancey established a $1.7-million endowment at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California in 1986 for research into sickle-cell anemia as a dedication to her grandson who died of the disease. Yancey died of pneumonia on January 26, 2008, at the age of 96.

5 – Alvin Ailey, dancer, choreographer and founder of the world famous Alvin Ailey Dance Theater was born on this day in 1931 in Rogers (Bell County). He made his Broadway debut in 1954 and in 1958 gained his first critical success for his choreography for Blues Suite, which also marked the beginning of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. His troupe, in 1970, became the first American dance company to tour the USSR in 50 years and received a 20-minute ovation for their performance in Leningrad.

5 – Alvin Ailey, dancer, choreographer and founder of the world famous Alvin Ailey Dance Theater was born on this day in 1931 in Rogers (Bell County). He made his Broadway debut in 1954 and in 1958 gained his first critical success for his choreography for Blues Suite, which also marked the beginning of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. His troupe, in 1970, became the first American dance company to tour the USSR in 50 years and received a 20-minute ovation for their performance in Leningrad.

5 — The University of Texas at Austin made a historic hire on this day in 2014 when it announced that Charlie Strong would become the school’s new head football coach, making him the program’s 29th head coach and the first African American to hold the position since UT began playing football in 1893. In fact, he also became the first black coach for any of the school’s major men’s programs. Strong, 59, signed a five-year deal paying him $5 million annually making the Batesville, Ark. native one of the highest paid coaches in the country.

5 — The University of Texas at Austin made a historic hire on this day in 2014 when it announced that Charlie Strong would become the school’s new head football coach, making him the program’s 29th head coach and the first African American to hold the position since UT began playing football in 1893. In fact, he also became the first black coach for any of the school’s major men’s programs. Strong, 59, signed a five-year deal paying him $5 million annually making the Batesville, Ark. native one of the highest paid coaches in the country.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Read his latest entry, “Misc. musings,” here.

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.