Thanksgiving soul food offers a window to African-American heritage

(Pictured: Collards with turkey kielbasa is a dish prepared by Carla Hall, co-host of “The Chew” and ambassador for the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Sweet Home Cafe.)

(The Baltimore Sun) The Thanksgiving Day meal for many African-Americans wouldn’t be complete without soul food, the cuisine that evolved from foods prepared and consumed by black slaves. Dishes such as pumpkin pie, rolls and stuffing are replaced with sweet potato pie, sweet cornbread and seafood dressing. Mixed greens, such as collards and mustard, take the place of green bean casserole. And baked macaroni and cheese — packed with various cheeses, eggs, milk and butter — is a must.

The distinctive dishes and the traditions associated with them, many of which have ties to Africa, create the all-important sense of togetherness for the family-centric holiday.

“It’s all about what you’re used to,” said Carla Hall from New York City after shooting an episode of the ABC talk show “The Chew,” which she co-hosts. “Soul food is important because it connects people to its culture and to its history and honoring where you come from. People come together through food. Everyone has that expression. And the expression can be made in many different ways.” (read more, including recipes)

The roots of black Thanksgiving: Why mac and cheese and potato salad are so popular

(The Washington Post) A year ago, I wrote a humorous piece about Thanksgiving based on a virally successful satirical guide to attending a predominantly black barbecue. I wanted to give readers of my blog a laugh while asking a serious question: Are the foods and other cultural traditions that mark African American Thanksgiving dinners just as different? “How to Survive Black Thanksgiving as a Non-Black Guest” was a hit because, much like the piece it was based on, it confronted, head on, ideas about the unspoken rules and understandings of our collective food culture.

(The Washington Post) A year ago, I wrote a humorous piece about Thanksgiving based on a virally successful satirical guide to attending a predominantly black barbecue. I wanted to give readers of my blog a laugh while asking a serious question: Are the foods and other cultural traditions that mark African American Thanksgiving dinners just as different? “How to Survive Black Thanksgiving as a Non-Black Guest” was a hit because, much like the piece it was based on, it confronted, head on, ideas about the unspoken rules and understandings of our collective food culture.

It made me realize that we lack a vocabulary that other ethnic groups have for the feelings and meanings behind, as one person put it, “how we be.” There should be, but there is no, African American version of Michael Pollan’s “Food Rules.” American ethnic groups have different versions of the same social slips, family politics and awkward moments — so that’s not unique. What is special is the approach to the foods of African American Thanksgiving meals and the ideas and history behind them.

The collective West and Central African cultural past and slavery are key ingredients that spice and flavor the African American table like no other. It goes without saying that much of “white Southern” holiday food owes its savor to the influence of black cooks and living in the vicinity of black cultures. (read more)

In Afro-Latinos, a vision of the trans-racial U.S.

The Houston Chronicle reports these days, in both Texas and the U.S. at large, skin color is an ever less reliable indicator of identity. According to a 2015 Pew survey, about a quarter of U.S. Hispanics identify themselves as Afro-Latino. Like Edwards, the vast majority (70 percent) are foreign-born. Afro-Latinos are generally descendants of African slaves brought to Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Most are biracial or multiracial. Being Afro-Latino, says Alain Lawo-Sukam, professor of Hispanic and Africana Studies at Texas A&M University, is less about skin color than about identity and a sense of belonging.

By their very existence, Afro-Latinos challenge the traditional “one-drop” view of race in the United States: the idea that one drop of African blood makes a person black. Afro-Latinos like Edwards aren’t simply black, white or Hispanic. They’re a combination — and as such, a vision of the United States’ racially and ethnically complex future. They’re a minority inside a minority; a melting pot within the melting pot.

“Our identity,” says Edwards, “is like the drop that is spilling the glass of the black-and-white system.” (read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

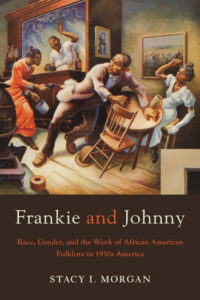

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Frankie and Johnny: Race, Gender, and the Work of African American Folklore in 1930s America,” by Stacy I. Morgan.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Frankie and Johnny: Race, Gender, and the Work of African American Folklore in 1930s America,” by Stacy I. Morgan.

Originating in a homicide in St. Louis in 1899, the ballad of “Frankie and Johnny” became one of America’s most familiar songs during the first half of the twentieth century. It crossed lines of race, class, and artistic genres, taking form in such varied expressions as a folk song performed by Huddie Ledbetter (Lead Belly); a ballet choreographed by Ruth Page and Bentley Stone under New Deal sponsorship; a mural in the Missouri State Capitol by Thomas Hart Benton; a play by John Huston; a motion picture, She Done Him Wrong, that made Mae West a national celebrity; and an anti-lynching poem by Sterling Brown.

In this innovative book, Stacy I. Morgan explores why African American folklore—and “Frankie and Johnny” in particular—became prized source material for artists of diverse political and aesthetic sensibilities. He looks at a confluence of factors, including the Harlem Renaissance, the Great Depression, and resurgent nationalism, that led those creators to engage with this ubiquitous song. Morgan’s research uncovers the wide range of work that artists called upon African American folklore to perform in the 1930s, as it alternately reinforced and challenged norms of race, gender, and appropriate subjects for artistic expression. He demonstrates that the folklorists and creative artists of that generation forged a new national culture in which African American folk songs featured centrally not only in folk and popular culture but in the fine arts as well.

This Week In Texas Black History, Nov. 20-26

23 — On this day in 1963, Baylor University’s athletic council announced it would integrate all of the school’s athletic teams, effective with the opening of the spring semester, Jan. 30, 1964. At the time, the school had no black students, but had announced its intention to open enrollment. John Bridgers, head football coach and athletic director said, “We don’t know of any Negro athletes right now that we’re interested in, but there may be some we will want to look at and investigate…there are some tremendous Negro athletes all over the country.” Bridgers said he personally agrees with the action of the trustees and the athletic council. “I feel it’s something that should be, from a standpoint of being right.” Ironically, Baylor was the first program in the Southwest Conference to have a black player take the field when running back John Westbrook, a walk-on, carried the ball twice in the Bears victory over Syracuse University on Sept. 10, 1966. A week later, Southern Methodist University‘s Jerry Levias became the SWC’s first black scholarship player.

23 — On this day in 1963, Baylor University’s athletic council announced it would integrate all of the school’s athletic teams, effective with the opening of the spring semester, Jan. 30, 1964. At the time, the school had no black students, but had announced its intention to open enrollment. John Bridgers, head football coach and athletic director said, “We don’t know of any Negro athletes right now that we’re interested in, but there may be some we will want to look at and investigate…there are some tremendous Negro athletes all over the country.” Bridgers said he personally agrees with the action of the trustees and the athletic council. “I feel it’s something that should be, from a standpoint of being right.” Ironically, Baylor was the first program in the Southwest Conference to have a black player take the field when running back John Westbrook, a walk-on, carried the ball twice in the Bears victory over Syracuse University on Sept. 10, 1966. A week later, Southern Methodist University‘s Jerry Levias became the SWC’s first black scholarship player.

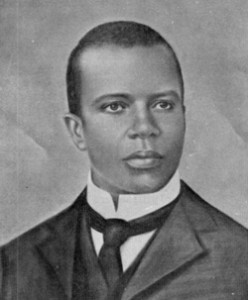

24 — Called the “King of Ragtime,” Scott Joplin was born this day in 1868 near Linden, Texas. (Some documents, however, refer to his birth as between June 1867 and mid-January 1868.) Joplin grew up in Texarkana, Texas and taught himself to play piano in the home where his mother worked as a domestic. Sheet music for his best-known piece, “Maple Leaf Rag,” sold over a million copies and his works also include a ballet and two operas. Joplin’s music was featured in the 1973 motion picture, “The Sting,” which won an Academy Award for its film score. In 1976, Joplin was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize for “Treemonisha,” the first grand opera by an African American.

24 — Called the “King of Ragtime,” Scott Joplin was born this day in 1868 near Linden, Texas. (Some documents, however, refer to his birth as between June 1867 and mid-January 1868.) Joplin grew up in Texarkana, Texas and taught himself to play piano in the home where his mother worked as a domestic. Sheet music for his best-known piece, “Maple Leaf Rag,” sold over a million copies and his works also include a ballet and two operas. Joplin’s music was featured in the 1973 motion picture, “The Sting,” which won an Academy Award for its film score. In 1976, Joplin was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize for “Treemonisha,” the first grand opera by an African American.

24 – Jazz pianist Teddy Wilson was born this day in Austin in 1912. Known as “the definitive swing pianist,” Wilson began his career in the late 1920s in various Midwest bands, and from 1935 to 1939, played on sessions that resulted in legendary vocalist Billie Holiday’s greatest work. He joined Benny Goodman in 1936, breaking the color barrier by performing on an equal footing with Goodman in trios, quartets and sextets. He is best known for his role as “Sam” in the Humphrey Bogart classic movie, “Casablanca,” in which he is the piano-player and singer (“As Time Goes By“) and the target for the line, “Play it (again, Sam)!”

24 – Jazz pianist Teddy Wilson was born this day in Austin in 1912. Known as “the definitive swing pianist,” Wilson began his career in the late 1920s in various Midwest bands, and from 1935 to 1939, played on sessions that resulted in legendary vocalist Billie Holiday’s greatest work. He joined Benny Goodman in 1936, breaking the color barrier by performing on an equal footing with Goodman in trios, quartets and sextets. He is best known for his role as “Sam” in the Humphrey Bogart classic movie, “Casablanca,” in which he is the piano-player and singer (“As Time Goes By“) and the target for the line, “Play it (again, Sam)!”

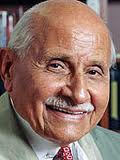

24 — Attorney, businessman and civil rights activist Percy Sutton was born on this date in 1920 in San Antonio. The son of a former slave, Sutton served in World War II with the Tuskegee Airmen, then settled in New York. In 1971, he co-founded the Inner City Broadcasting Corporation, which purchased WLIB-AM, making it the first black-owned station in New York City. He earned a law degree in 1950 and served in the New York State Assembly before taking over as Manhattan borough president in 1966, becoming the state’s highest-ranking black elected official. Sutton also headed a group that owned the Amsterdam News, the second-largest black weekly newspaper in the country.

24 — Attorney, businessman and civil rights activist Percy Sutton was born on this date in 1920 in San Antonio. The son of a former slave, Sutton served in World War II with the Tuskegee Airmen, then settled in New York. In 1971, he co-founded the Inner City Broadcasting Corporation, which purchased WLIB-AM, making it the first black-owned station in New York City. He earned a law degree in 1950 and served in the New York State Assembly before taking over as Manhattan borough president in 1966, becoming the state’s highest-ranking black elected official. Sutton also headed a group that owned the Amsterdam News, the second-largest black weekly newspaper in the country.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Post Obama = Neo Hate” Read it

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Post Obama = Neo Hate” Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.