The National Museum of African American History and Culture: “I, Too, Sing America”

(Pictured: A statue of Thomas Jefferson stands in front of a stack of bricks marked with the names of people he owned.)

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened on Sept. 24 in Washington after a long journey. Thirteen years since Congress and President George W. Bush authorized its construction, the 400,000-square-foot building stands on a five-acre site on the National Mall, close to the Washington Monument. President Obama will speak at its opening dedication.

Appropriately for a public museum at the heart of Washington’s cultural landscape, the museum’s creators did not want to build a space for a black audience alone, but for all Americans. In the spirit of Langston Hughes’s poem “I, Too,” their message is a powerful declaration: The African-American story is an American story, as central to the country’s narrative as any other, and understanding black history and culture is essential to understanding American history and culture.

Read the story and view images of several of the museum’s displays in this special section from the NY Times.

African-American Monument Being Installed at Texas Capitol

After more than two decades of effort by lawmakers to install a monument at the Capitol celebrating African-Americans, the main components of a bronze and granite memorial were quietly lowered onto the south lawn on Sep. 27.

After more than two decades of effort by lawmakers to install a monument at the Capitol celebrating African-Americans, the main components of a bronze and granite memorial were quietly lowered onto the south lawn on Sep. 27.

Denver-based sculptor Ed Dwight proposed the Texas African-American History Memorial to celebrate more than 400 years of achievements by black Texans. The sculpture, which will be 27 feet high and be 32 feet long when completed, stands near the Capitol’s main entrance.

“It’s really extraordinary,” Dwight said. “This one is right in your face, and you’ll be able to walk up and touch it and associate with it.” (read more)

Austin Muny named one of nation’s ‘most endangered historic places’

The National Trust for Historic Preservation named Lions Municipal Golf Course on Wednesday to its list of America’s most endangered historic places, calling the course a “civil rights landmark” with an uncertain future.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation named Lions Municipal Golf Course on Wednesday to its list of America’s most endangered historic places, calling the course a “civil rights landmark” with an uncertain future.

The National Trust, a private, nonprofit organization based in Washington, also included El Paso’s Chihuahuita and El Segundo Barrio Neighborhoods on its annual list of 11 sites. The core of that city’s cultural identity is threatened with demolition of homes and small businesses, the group said.

Lions Municipal, also known as Muny, is considered one of the earliest municipal golf courses in the former Confederate states to be desegregated, if not the first. (read more)

Photo: General Marshall, former caddy and senior golfer, stands next to the Texas Historical marker after its dedication at Lion’s Municipal Golf Course in 2009. (Photo, Rodolfo Gonzalez, American-Statesman)

Black College Football Hall of Fame announces class of 2017 finalists

The Black College Football Hall of Fame as announced the 25 finalists for induction as its Class of 2017. The list includes 20 players and five coaches, with two former Dallas Cowboys, Everson Walls (DB, Grambling) and Tim Newsome (RB, Winston-Salem State) among the players. One of the coaching finalists is Arnett “Ace” Mumford, the revered head coach at Southern University in Baton Rouge who also coached at Jarvis Christian (Hawkins, Texas), 1924-1926, Bishop College (Marshall), 1927-1929, and Texas College, 1931-1935, where he won a black college national championship in 1935.

The Black College Football Hall of Fame as announced the 25 finalists for induction as its Class of 2017. The list includes 20 players and five coaches, with two former Dallas Cowboys, Everson Walls (DB, Grambling) and Tim Newsome (RB, Winston-Salem State) among the players. One of the coaching finalists is Arnett “Ace” Mumford, the revered head coach at Southern University in Baton Rouge who also coached at Jarvis Christian (Hawkins, Texas), 1924-1926, Bishop College (Marshall), 1927-1929, and Texas College, 1931-1935, where he won a black college national championship in 1935.

The finalists were selected from a field of over 175 nominees by a 13-member selection committee composed of prominent journalists, commentators, historians, former NFL general managers and football executives and represent 10 Super Bowl rings, 46 Pro Bowl and AFL/NFL All-Star selections and 19 Black College Football National Championships.“The number of players that Historically Black Colleges and Universities sent to the NFL is amazing,” said NFL player personnel expert Gil Brandt, a member of the selection committee. “Football history runs deep at these schools, and it’s an important part of history to recognize and preserve.”

The Class of 2017 inductees — five players and one coach — will be announced on October 26. Induction ceremonies will be held on February 25, 2017 in Atlanta.

Read more and see the complete list here.

Related: Historically Black Schools Pay the Price for a Football Paycheck

These matchups, usually scheduled early in the season, are called “guarantee games,” because the visiting team is guaranteed an appearance fee. In other words, they are paid handsomely to get knocked crazy. Here are some of the scores and payouts involving HBCU teams in guarantee games this season: Howard University’s opening game was against Maryland ($350,000); it lost, 52-13. The next week it lost to Rutgers, 52-14 ($350,000). Prairie View A&M was beaten by Texas A&M, 67-0 ($450,000). (read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice,” by Gary M. Lavergne.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice,” by Gary M. Lavergne.

On February 26, 1946, an African American from Houston applied for admission to the University of Texas School of Law. Although he met all of the school’s academic qualifications, Heman Marion Sweatt was denied admission because he was black. He challenged the university’s decision in court, and the resulting case, Sweatt v. Painter, went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in Sweatt’s favor. The Sweatt case paved the way for the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka rulings that finally opened the doors to higher education for all African Americans and desegregated public education in the United States.

In this engrossing, well-researched book, Gary M. Lavergne tells the fascinating story of Heman Sweatt’s struggle for justice and how it became a milestone for the civil rights movement.

This Week In Texas Black History, Oct. 2-8

3 – On this day in 2014, Dallas businessman and philanthropist Comer Cottrell passed away from natural causes. A native of Mobile, Ala., Cottrell founded Pro-Line, hair care products for African-Americans, in Los Angeles in 1970. He is noted for popularizing the “Jheri curl.” In 1980, he relocated the business to Dallas where it became the largest black-owned firm in the Southwest and one of the most profitable black companies in the United States. Cottrell was the first black member of the powerful Dallas Citizens Council and became part owner of Texas Rangers baseball team in 1989, becoming the first African-American to hold such a stake in a Major League Baseball team.

3 – On this day in 2014, Dallas businessman and philanthropist Comer Cottrell passed away from natural causes. A native of Mobile, Ala., Cottrell founded Pro-Line, hair care products for African-Americans, in Los Angeles in 1970. He is noted for popularizing the “Jheri curl.” In 1980, he relocated the business to Dallas where it became the largest black-owned firm in the Southwest and one of the most profitable black companies in the United States. Cottrell was the first black member of the powerful Dallas Citizens Council and became part owner of Texas Rangers baseball team in 1989, becoming the first African-American to hold such a stake in a Major League Baseball team.

3 – Heman Sweatt, whose landmark case against the University of Texas Law School in 1950 set a precedent for Brown v. Board of Education and the integration of all public schools in the U.S., died on this day in 1982 in Atlanta, Ga. Sweatt, was born in Houston and graduated from Jack Yates High School and then Wiley College. Before his attempts to enter UT, he studied biology at the University of Michigan with intentions of entering medical school. After resolution of his case, Sweatt attended the school for two years, but the emotional and physical toll from his quest forced him to leave school. He received a scholarship to study social work at Atlanta University and earned a master’s degree in community organizations in 1954. He later became assistant director of the National Urban League‘s southern regional office in Atlanta. (See, TIPHC Bookshelf: “Before Brown — Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice,” by Gary M. Lavergne, University of Texas Press.)

3 – Heman Sweatt, whose landmark case against the University of Texas Law School in 1950 set a precedent for Brown v. Board of Education and the integration of all public schools in the U.S., died on this day in 1982 in Atlanta, Ga. Sweatt, was born in Houston and graduated from Jack Yates High School and then Wiley College. Before his attempts to enter UT, he studied biology at the University of Michigan with intentions of entering medical school. After resolution of his case, Sweatt attended the school for two years, but the emotional and physical toll from his quest forced him to leave school. He received a scholarship to study social work at Atlanta University and earned a master’s degree in community organizations in 1954. He later became assistant director of the National Urban League‘s southern regional office in Atlanta. (See, TIPHC Bookshelf: “Before Brown — Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, and the Long Road to Justice,” by Gary M. Lavergne, University of Texas Press.)

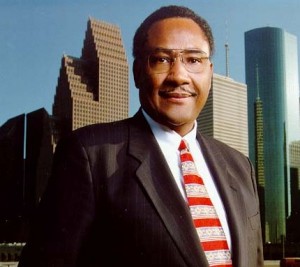

4 – Born on this day in 1937 in Wewoka, Oklahoma (southeast of Oklahoma City), Lee Patrick Brown was the first African-American police chief and then the first African-American mayor for the city of Houston. Brown’s parents were sharecroppers and moved to San Jose, California where he began his law enforcement career as a police officer while a student at San Jose State University. There, he earned degrees in criminology (1960) and sociology (1964 – master’s). He also earned a master’s and then a doctorate in criminology from the University of California-Berkeley. Brown was the first African-American police chief for three cities: Atlanta (1978), Houston (1982), and New York City (police commissioner, 1990). In Atlanta, he was chief during the Atlanta Child Murders case which resulted in the arrest and conviction of Wayne B. Williams. In Houston, Brown pioneered the community policing concept that included officers patrolling neighbors on foot. In 1993, he was appointed director of the White House Office of Drug Control Policy, and in 1997 was elected mayor of Houston and served three two-year terms.

4 – Born on this day in 1937 in Wewoka, Oklahoma (southeast of Oklahoma City), Lee Patrick Brown was the first African-American police chief and then the first African-American mayor for the city of Houston. Brown’s parents were sharecroppers and moved to San Jose, California where he began his law enforcement career as a police officer while a student at San Jose State University. There, he earned degrees in criminology (1960) and sociology (1964 – master’s). He also earned a master’s and then a doctorate in criminology from the University of California-Berkeley. Brown was the first African-American police chief for three cities: Atlanta (1978), Houston (1982), and New York City (police commissioner, 1990). In Atlanta, he was chief during the Atlanta Child Murders case which resulted in the arrest and conviction of Wayne B. Williams. In Houston, Brown pioneered the community policing concept that included officers patrolling neighbors on foot. In 1993, he was appointed director of the White House Office of Drug Control Policy, and in 1997 was elected mayor of Houston and served three two-year terms.

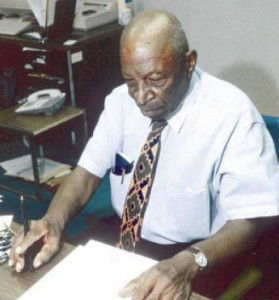

7 – George McElroy, “Mr. Mac,” the first black columnist for the Houston Post, died on this day in 2006. A Houston native, McElroy was also the first African-American to earn a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri, which he attended on a scholarship from the Wall Street Journal. McElroy began his career at age 16 earning $2 a week writing a youth column for the Houston Informer, the city’s oldest black newspaper. Years later, he became the paper’s executive editor. McElroy, the recipient of numerous honors, taught journalism at Houston’s black high schools, as well as Texas Southern University (his alma mater) and the University of Houston.

7 – George McElroy, “Mr. Mac,” the first black columnist for the Houston Post, died on this day in 2006. A Houston native, McElroy was also the first African-American to earn a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri, which he attended on a scholarship from the Wall Street Journal. McElroy began his career at age 16 earning $2 a week writing a youth column for the Houston Informer, the city’s oldest black newspaper. Years later, he became the paper’s executive editor. McElroy, the recipient of numerous honors, taught journalism at Houston’s black high schools, as well as Texas Southern University (his alma mater) and the University of Houston.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “A change has come?” Read it

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “A change has come?” Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.