How Texas Prevented Black Women From Voting Decades After The 19th Amendment

Texas ratified the 19th Amendment on June 28, 1919, then shut out black voters by creating the “white primary.”

(Image credit: Michelle Lam/Houston Public Media)

(Houston Public Media) In 1918, when she was 25 years old, Christia Adair went door-to-door organizing for women’s right to vote in Texas.

“This effort was to pass a bill where women would be able to vote like men,” Adair remembered later in a 1977 oral history interview with the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College.

“Well, we still didn’t know that that didn’t mean us. But we helped.”

When the bill passed, Adair went to the polls for the first time. The memory of what happened stuck with her the rest of her life.

“The white women were going to vote,” she said. “And we dressed up and went to vote, and when we got down there, well, we couldn’t vote. They gave us all different kinds of excuses why. So finally one woman, a Mrs. Simmons, said, ‘Are you saying that we can’t vote because we’re Negroes?’ And he said, “Yes, Negroes don’t vote in primary in Texas.’ So that just hurt our hearts real bad.” (more)

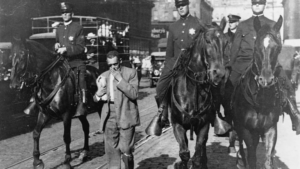

Red Summer of 1919: How Black WWI Vets Fought Back Against Racist Mobs

When dozens of brutal race riots erupted across the U.S. in the wake of World War I and the Great Migration, black veterans stepped up to defend their communities against white violence.

Mounted police round up African Americans and escort them to a safety zone during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

(History) The ink had barely dried on the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended World War I, when recently returned black veterans grabbed their guns and stationed themselves on rooftops in black neighborhoods in Washington D.C., prepared to act as snipers in the case of mob violence in July of 1919. Others set up blockades around Howard University, a black intellectual hub, creating a protective ring around residents.

White sailors recently home from the war had been on a days-long drunken rampage, assaulting, and in some cases lynching, black people on the capitol’s streets. The relentless onslaught proved contagious, escalating in dozens of cities across the U.S. in what would become known as the The Red Summer.

The racist attacks in 1919 were widespread, and often indiscriminate, but in many places, they were initiated by white servicemen and centered upon the380,000 black veterans who had just returned from the war. “Because of their military service, black veterans were seen as a particular threat to Jim Crow and racial subordination,” notes a report by the Equal Justice Initiative.

Indeed, many African American soldiers returned from the war armed with a renewed determination to fight segregation and a near-constant barrage of brutality. (more)

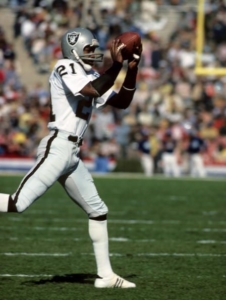

Raiders receiving great Branch dies at age 71

PVIL star in track and football at Houston’s E.E. Worthing High School

Cliff Branch, a four-time Pro Bowl and three-time All-Pro receiver with the Raiders, has died, the team announced Saturday (Aug. 3).

Cliff Branch, a four-time Pro Bowl and three-time All-Pro receiver with the Raiders, has died, the team announced Saturday (Aug. 3).

Branch turned 71 on Thursday.

(Note: Branch was from Sunnyside, in southeast Houston, and graduated in 1967 from Worthing HS, where he was a Prairie View Interscholastic League state sprint champion in 1966 and 1967. Branch was the first schoolboy in Texas history to run the 100-yard dash in 9.3 seconds.)

“Cliff Branch touched the lives of generations of Raiders fans,” the team said in a release. “His loss leaves an eternal void for the Raiders Family, but his kindness and loving nature will be fondly remembered forever. Cliff’s on-field accomplishments are well documented and undeniably Hall of Fame worthy, but his friendship and smile are what the Raider Nation will always cherish.”

According to the Bullhead City (Arizona) Police Department, Branch was found dead in his hotel room Saturday afternoon. Police there said an initial investigation revealed no foul play and that Branch died of natural causes. (more)

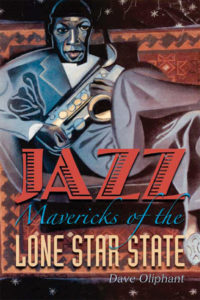

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State,” by Dave Oliphant.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State,” by Dave Oliphant.

Jazz is one of America’s greatest gifts to the arts, and native Texas musicians have played a major role in the development of jazz from its birth in ragtime, blues, and boogie-woogie to its most contemporary manifestation in free jazz. Dave Oliphant began the fascinating story of Texans and jazz in his acclaimed book Texan Jazz, published in 1996. Continuing his riff on this intriguing musical theme, Oliphant uncovers in this new volume more of the prolific connections between Texas musicians and jazz.

Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State presents sixteen published and previously unpublished essays on Texans and jazz. Oliphant celebrates the contributions of such vital figures as Eddie Durham, Kenny Dorham, Leo Wright, and Ornette Coleman. He also takes a fuller look at Western Swing through Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies and a review of Duncan McLean’s Lone Star Swing. In addition, he traces the relationship between British jazz criticism and Texas jazz and defends the reputation of Texas folklorist Alan Lomax as the first biographer of legendary jazz pianist-composer Jelly Roll Morton. In other essays, Oliphant examines the links between jazz and literature, including fiction and poetry by Texas writers, and reveals the seemingly unlikely connection between Texas and Wisconsin in jazz annals. All the essays in this book underscore the important parts played by Texas musicians in jazz history and the significance of Texas to jazz, as also demonstrated by Oliphant’s reviews of the Ken Burns PBS series on jazz and Alfred Appel Jr.’s Jazz Modernism.

This Week in Texas Black History

Aug. 4

On this day in 1840, minister and Republican State Senator Matthew Gaines was born into slavery in Pineville, La. In 1863, he was sold to a planter in Fredericksburg where he worked as a blacksmith and a sheepherder. After emancipation, he relocated to Washington County where he became a leader of the black community, and was elected as a state senator during Reconstruction to represent the Sixteenth District. He was a staunch proponent for education, prison reform, the protection of blacks at the polls, the election of blacks to public office, and tenant-farming reform.

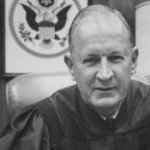

Aug. 4

District Court Judge Ben Connally labeled the Houston school board‘s desegregation plan a “palpable sham and subterfuge” on this day in 1960. Houston’s 173 schools comprised the largest segregated school district in the U.S., and in 1957 Connally ordered the schools to be integrated “with all deliberate speed.” However, in August, 1959, the board revealed in a 373-page report to the Court that it had no desegregation plan and requested additional time to prepare one. Connally ordered the board to submit a plan by June 1, 1960. It was that plan which enraged Connally. In it, the board sought to integrate only three schools, but stated that no child need attend the integrated schools. As a result, Connally ordered desegregation to commence in all first grades in September 1960 and to proceed at one grade per year thereafter. The board’s attitude may have been typified by parliamentarian Bertie Maughmer who had won election to the board in 1956 proudly declaring: “I’d rather go to jail than see my kids go to school with niggers.”

Aug. 5

On this day in 1880, Gertrude E. Rush, attorney and civil rights activist was born in Navasota. Rush was also an accomplished playwright and author. The daughter of a Baptist minister, her family moved to the Midwest and settled in Oskaloosa, Iowa, southeast of Des Moines. Rush studied law while working in the office of her attorney-husband James B. Rush and was admitted to the Iowa State Bar in 1918 as the state’s first Black female lawyer and only such lawyer in the state until 1950. In 1921, she was elected president of Iowa’s Colored Bar Association, making her the first woman in the nation top lead a state bar association that included both male and female members. However, she was denied admission to the American Bar Association, and in 1925 Rush and four other black lawyers founded the Negro Bar Association (later renamed the National Bar Association). Rush also wrote numerous plays, pageants, and hymns, such as the popular “Jesus Loves the Little Children” (1907).

Aug. 6

President Lyndon Johnson, on this day signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolishing literacy tests and poll taxes designed to disenfranchise African American and other minority and poor voters. Johnson signed the act in the President’s Room just off the U. S. Senate chamber floor, the same location and on the same date when 104 years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had signed the Confiscation Act of 1861. That bill freed slaves being used by the Confederate States in the war effort, an early move towards Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation. In some Southern states, voting officials asked potential black voters to recite the entire U.S. Constitution or explain complex provisions of state laws before they could cast their ballot. (As a means of discriminating against Irish-Catholic immigrants, Connecticut adopted the nation’s first literacy test for voting in 1855.) The Voting Rights Act vastly improved voter turnout among blacks and also gave them the legal means to challenge voting restrictions, which were not readily enforced in the South and often simply ignored. Texas never utilized literacy tests, but did institute a poll tax in 1902 requiring eligible voters to pay between $1.50 and $1.75 to register to vote. The poll tax was finally abolished for national elections by the 24th Amendment in 1964 which was ratified by all but 12 states, including Texas, which finally did on May 22, 2009.

Aug. 9

Al Freeman, actor, died on this day in 2012 at age 78 in Washington, D.C. A San Antonio native, Freeman starred on Broadway in the 1960s in productions such as “Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright” and in plays by James Baldwinand LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), including “Blues for Mister Charlie.” In 1979, Freeman became the first African American to receive a Daytime Emmy for a soap opera for his role as a police captain on “One Life to Live.” He also drew critical acclaim for his portrayal of Malcolm X in the mini-series “Roots: The Next Generations,” and in 1991 played Elijah Muhammad in the Spike Lee movie “Malcolm X.”

Aug. 9

This day marks the death, in 1912, of George Smith, founder and first principal of the first school for African Americans in Brownwood. Smith was a teacher, former Buffalo Soldier (10th Cavalry), and an elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He had been born into slavery in Virgina in 1847. After his military service ended at Fort Concho in San Angelo, he was recruited by AME Bishop Richad H. Cain to organize AME churches in communities where there were none. Smith traveled 100 miles northeast to Brownwood, where he found one AME church, but no school for black children. He organized and taught classes at various locations in the town, including the AME church. Five years after Smith’s death, a four-room stone facility was built for the school and, in 1934, was named in honor of former principal Rufus F. Hardin.

Aug. 10

On this day in 1918, jazz saxophonist Arnett Cobb was born in Houston. He was exposed to music at an early age; his grandmother taught him to play the piano when he was about 10 years old. He soon picked up the violin. As the only violin in an 80-piece brass band at Phillis Wheatley High School, he switched to saxophone in order to be heard. Known as the “Wild Man of the Tenor Sax,” Cobb made his professional debut with Frank Davis in 1933. Cobb played with Chester Boone from 1934-1936 and with Milt Larkin from 1936-1942. In 1942, he replaced Illinois Jacquet in Lionel Hampton‘s band, where he remained until 1947 when he left to form his own band. Serious injuries resulting from being hit by a car when he was 10 and an automobile accident in 1951 plagued him throughout his career, but never prevented Cobb from helping to shape and define what become known as the Texas-tenor sound.

On this day in 1918, jazz saxophonist Arnett Cobb was born in Houston. He was exposed to music at an early age; his grandmother taught him to play the piano when he was about 10 years old. He soon picked up the violin. As the only violin in an 80-piece brass band at Phillis Wheatley High School, he switched to saxophone in order to be heard. Known as the “Wild Man of the Tenor Sax,” Cobb made his professional debut with Frank Davis in 1933. Cobb played with Chester Boone from 1934-1936 and with Milt Larkin from 1936-1942. In 1942, he replaced Illinois Jacquet in Lionel Hampton‘s band, where he remained until 1947 when he left to form his own band. Serious injuries resulting from being hit by a car when he was 10 and an automobile accident in 1951 plagued him throughout his career, but never prevented Cobb from helping to shape and define what become known as the Texas-tenor sound.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

Hidden In Plain Sight

In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote The Souls of Black Folk in which he claimed: “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.” That was 1903. American society is in the last year of the second decade of the twenty-first century, and I wonder if that famous quote still applies. In 1903, Jim Crow dominated every aspect of American life and forced the black community into the shadows. Du Bois used”…(more)

A community under siege: the Summer of 1919

I wonder Is there anybody here who late at midnight sheds briny tears all because you didn’t have no one to help you along the way and oh Lord? And if there’s anyone Lord Let me tell you, let me tell you what I’ve done I’ve achieved to be a fence around me but take me everyday I told him So what Jesus be a fence all around me When I get burned So Jesus…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.