They Introduced the World to Songs of Slavery. It Almost Broke Them.

The Jubilee Singers were a global sensation. But an aggressive touring schedule would leave the young performers exhausted, underpaid, and in some cases, dead.

(Topic Magazine) It was late December of 1871, and Henry Ward Beecher, the minister of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, had invited a group of young men and women from Fisk University in Nashville to travel to New York to perform for his congregation. “There is a band of singers here,” Beecher announced to the audience, “every one of whom has been baptized in slavery … they are coming to the East to see if they can raise some little funds for their education and elevation.” The group of performers—five women and four men between the ages of 14 and 25—looked out of place among the well-heeled throng of white church attendees; one observer later described the girls as “dressed in water-proofs, and clothed about the neck with long woolen comforters to protect their throats.” But when the nine young African Americans began to sing, the Plymouth parishioners found themselves charmed and moved, even transported, by the spirituals, which told stories of bondage and emancipation. “The first hymn they sang was ‘O, how I love Jesus!’,” the observer wrote. “I shall never forget the rich tones as they mingled their voices in a melody so beautiful and touching I scarcely knew whether I was ‘in body or out of body.’”

“Songs of jubilee” were also used to manipulate and coerce: As historian Katrina Dyonne Thompson details in her 2014 book Ring Shout, Wheel About: The Racial Politics of Music and Dance in North American Slavery, during nearly two centuries of chattel slavery, enslaved people were regularly expected to perform on demand and in public by slave traders, who wished for them to appear carefree and cheerful to potential buyers; in his autobiography, one formerly enslaved man, the pastor and abolitionist John Sella Martin, recalled that his traders made slaves sing to “prevent any expression of sorrow for those who are being torn away from them.” In addition, owners of slaves with skills in the performing arts would often pit them against other enslaved performers and place bets on the outcome, in a kind of inter-plantation talent contest. “Slaves,” as Frederick Douglass explained in his 1855 autobiography, “are generally expected to sing as well as to work.”

“He would keep us singing them all day until he was satisfied that we had every soft or loud passage to suit his fastidious taste.”

The story of the Jubilee Singers—who, less than a decade before their appearance at Plymouth Church, had been transported from slavery to emancipation to higher education and to fame—thrilled audiences, first in America and eventually in Europe. But it was the Singers’ white producers—the abolitionists and educators who encouraged them to perform these songs for the public, and eventually the tour managers who would underpay and overwork them—who developed their act and controlled their image, foreshadowing the familiar story of recording-industry exploitation that later affected the careers and fortunes of black musicians in the United States, to often devastating effect. (more)

Perspective: The hidden heroes of the civil rights movement

In classrooms across the nation, black teachers worked as “intellectual activists”

At the Warren County Court in Virginia in 1958, black families filed a lawsuit that forced the county high school to admit black students. (Pete Marovich for The Washington Post)

(The Washington Post) In June 19, African Americans across the United States will celebrate Juneteenth, the day in 1865 that marked the end of slavery in Texas, and with it, the complete abolition of the practice in the United States. On this day, we realize the moment when the ideals of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation reached every state. While the holiday represents a relatively unknown marker in American history, it is a powerful reminder in the African American community of the strides that we and our ancestors have taken to realize the ideals of racial equality, freedom and justice.

But Juneteenth is not only a day of celebration. It also sheds light on the national struggle to fully realize these ideals, marked by recent tragedies in Ferguson, Mo.; Charleston; and Charlottesville. In grappling with the challenge of ongoing racial violence and inequality, we should consider the often forgotten work of educators who taught during one of the most racially turbulent and democratically challenging periods in recent history — the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s. (more)

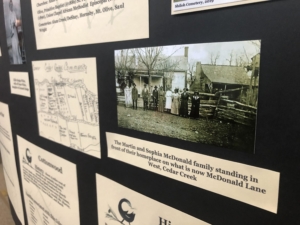

Museum exhibit gives life to freed slaves’ history in Bastrop County

The Bastrop County Historical Museum new exhibit on freedom colonies features pictures and old hand drawn maps that illustrate life within a Bastrop County freedom colony in the late 19th and early 20th century. (Brandon Mulder/Bastrop Advertiser)

(Austin American-Statesman) The Bastrop County Historical Museum is uncovering shreds of local black history.

A months-long project that includes crowd-sourced artifacts, photographs and oral histories of black families in Bastrop County has unearthed new findings about the county’s African American roots — specifically, the locations and characteristics of the many freedom colonies established by emancipated slaves.

The project’s big discovery is the identification of a dozen previously unknown freedom colonies in the county, nearly doubling the total 13 colonies the Texas State Historical Association recorded in 2003. (more)

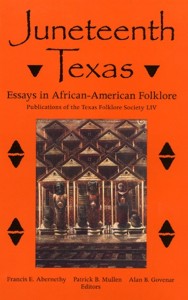

TIPHC Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas, Essays in African-American Folklore,” edited by Francis Edward Abernethy, Alan B. Govenar, and Patrick B. Mullen

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Juneteenth Texas, Essays in African-American Folklore,” edited by Francis Edward Abernethy, Alan B. Govenar, and Patrick B. Mullen

Juneteenth Texas explores African-American folkways and traditions from both African-American and white perspectives. Included are descriptions and classifications of different aspects of African-American folk culture in Texas; explorations of songs and stories and specific performers such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Manse Lipscomb, and Bongo Joe; and a section giving resources for the further study of African-Americans in Texas.

“[T]he editors have contributed significantly to making our past relevant to our present in Juneteenth Texas, a collection of essays that explore African-American folkways and traditions. Drawing upon the expertise of folklorists, musicologists, filmmakers, historians, anthropologists and just plain folks . . . the objective is to use the prism of African-American folklore to enlighten all Americans about our common culture . . . So evocative is the writing on musical folklore, one longs for a companion CD to add even more vitality to . . . an excellent text.”—Dallas Morning News

This collection, with contributions by Glen Alyn, T. Lindsey Baker, Lorenzo Thomas, Dave Oliphant, Alvia Wardlaw, Patricia Smith Prather and others, contains essays based on personal experiences and reminiscences about the past as well as the present, from both African-American and white perspectives; descriptions and classifications of different aspects of African-American folk culture in Texas; studies of specific genres of folklore, such as songs and stories; studies of specific performers such as Lightin’ Hopkins, Manse Lipscomb, and Bongo Joe; studies of particular folklorists who were important in the collecting of African-American folklore in Texas, such as J. Mason Brewer; a section giving resources for the further study of African Americans in Texas.

This Week in Texas Black History

Jun 18

On this day in 2005, renowned surgeon and educator Claude H. Organ, Jr. died in Berkeley, Ca. of heart-related problems at age 78. A Marshall native, Organ was accepted to the University of Texas medical school, but when the school discovered he was black, it offered to pay the difference in tuition for him to attend another school. He graduated from Xavier University a black college in New Orleans and later received a degree from Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha. Organ developed two successful surgical residency programs, first at Creighton and later at the University of California/Davis-University of California, San Francisco East Bay Surgery Department. During his tenure at San Francisco he served as the first African American editor of the Archives of Surgery, the largest surgical journal in the English-speaking world.

On this day in 2005, renowned surgeon and educator Claude H. Organ, Jr. died in Berkeley, Ca. of heart-related problems at age 78. A Marshall native, Organ was accepted to the University of Texas medical school, but when the school discovered he was black, it offered to pay the difference in tuition for him to attend another school. He graduated from Xavier University a black college in New Orleans and later received a degree from Creighton University School of Medicine in Omaha. Organ developed two successful surgical residency programs, first at Creighton and later at the University of California/Davis-University of California, San Francisco East Bay Surgery Department. During his tenure at San Francisco he served as the first African American editor of the Archives of Surgery, the largest surgical journal in the English-speaking world.

Jun 19

On this day in 1865, Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and delivered the news about the Emancipation Proclamation, which had originally been issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Granger, supposedly from a balcony at Ashton Villa, one of the state’s first brick structures, read General Order No. 3, which officially freed 250,000 slaves in Texas. The order read: “The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” In 1979 Governor William P. Clements signed an act making the day a state holiday. The first state-sponsored Juneteenth celebration took place the next year.

Jun 20

On this day in 1967, a jury in federal court in Houston found heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali guilty of draft evasion. Ali, who had a residence in Houston at the time, was known to the government as Cassius Clay and was sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Ali’s contention was that the draft boards in Louisville, Ky., his hometown, and in Houston had acted improperly by not granting him a deferment as a minister in the Nation of Islam, however, he was convicted of violating the U.S. Selective Service laws by refusing to be drafted. He had been ordered to report to a Houston induction station on April 28, 1967 and did, but refused to step forward when his named was called, afterwards saying, ”Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” He was immediately stripped of his boxing license and his title and was banned from boxing for three years. He stayed out of prison as his case was appealed. The case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and on June 28, 1971 (Clay, aka Ali, v. United States) the Court ruled 8-0, with Justice Thurgood Marshall abstaining, that Ali met the three standards for conscientious objector status: that he opposed war in any form, that his beliefs were based on religious teaching and that his objection was sincere. However, Ali had already resumed boxing on October 26, 1970, knocking out Jerry Quarry in Atlanta in the third round.

Jun 21

Dallas Cowboys’ running back Duane Thomas was born on this day in 1947 in Dallas. Thomas had an exceptional career at Lincoln High School, then at West Texas State, where he teamed with another future pro running back, Mercury Morris. Thomas was the Cowboys’ first round pick (23rd overall) in the 1970 draft and was the NFC Rookie of the Year after leading Dallas in rushing (803 yards). He led the league in rushing in 1971 and led the Cowboys with 95 rushing yards and a touchdown in Dallas’ first Super Bowl victory, a 24-3 win over the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl VI.

Jun 21

On this date in 1955, the El Paso School Board voted to abolish segregation in the city’s public schools becoming the first district in Texas to unconditionally favor desegregation. The move came one year after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down segregation in public schools in the Brown v. Board of Education decision. El Paso board member Ted Andress made the motion: “The School Board members have taken notice of the recent Supreme Court decision on compulsory segregation (which was enforced in Texas). I think it is time that this board makes the prompt and reasonable start toward integration that should be made. I move that we comply with all rulings of the Supreme Court and that segregation on a compulsory or involuntary basis shall not be enforced in the El Paso Public Schools.” The motion took effect with the opening of schools for the 1955 fall semester.

Jun 22

On this date in 1962, basketball great Clyde “The Glide” Drexler was born in New Orleans. Drexler graduated from Sterling High School in Houston then attended the University of Houston where he starred as a member of the teams known as Phi Slama Jama for their fast pace, dunking, high flying style. Drexler was the 14th overall pick of the 1983 NBA Draft by the Portland Trail Blazers and twice led the team to the NBA Finals (1990, 1992). However, he played alongside center and former UH teammate Hakeem Olajuwon on the Houston Rockets 1995 NBA title team. Drexler was a 10-time All-Star, a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic dream team, and named one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history. He was elected to Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2004.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin is an assistant professor of history at Prairie View A&M University. Even though he was a military “brat,” he still considers San Antonio home. Like his father and brother, Ron joined the U.S. Air Force and while enlisted received his undergraduate degree from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas. After his honorable discharge, he completed graduate degrees from Texas Southern University. Goodwin’s book, Blacks in Houston, is a pictorial history of Houston’s black community. His most recent book, Remembering the Days of Sorrow, examines the institution of slavery in Texas from the perspective of the New Deal’s Slave Narratives.

Recent Posts

The Everlasting Light

Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it givith light unto all that are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven. — Matthew 5: 14-16

This is the month set aside to honor…(more)

The Return of the Silent Majority

Fifty years ago, in January 1969, Richard Nixon was sworn in as the thirty-seventh president of the United States. His legacy as President was marred by the Watergate investigations and his eventual resignation from office which overshadowed the way in which he won the office. His central campaign rhetoric was designed to garner support from white Southerners (otherwise known in history as the “Silent Majority”) whose racial beliefs leaned heavily towards the support of white…(more)

Submissions wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.