Jimena Duran Castellanos is a native of Hidalgo, Mexico and a junior in the PVAMU School of Architecture. She researched and wrote this essay as a project during her 2019 summer internship with the TIPHC. Jimena is also a student-athlete as a member of the Panthers’ women’s tennis team. She is proud that tennis has given her the opportunity to study and play in the United States, learn the country’s cultures as well as that of Texas: “I have been living in Texas for almost three years and living here makes me love my roots and culture even more. But now, I love Texas too. I have two homes!”

Jimena Duran Castellanos is a native of Hidalgo, Mexico and a junior in the PVAMU School of Architecture. She researched and wrote this essay as a project during her 2019 summer internship with the TIPHC. Jimena is also a student-athlete as a member of the Panthers’ women’s tennis team. She is proud that tennis has given her the opportunity to study and play in the United States, learn the country’s cultures as well as that of Texas: “I have been living in Texas for almost three years and living here makes me love my roots and culture even more. But now, I love Texas too. I have two homes!”

I am Mexican. I understand that the history of my country is very dramatic because of the cultural shock that happened between Mexican natives and Spaniards after the discovery of the “New World”. Then, settlers brought African and Asian people to New Spain (Mexico) and that produced more changes in the country’s social structure, as the mixture of cultures and races led to complications between races. In Mexico, people’s race does not determine what kind of life a person can have. Now, people are more concerned with their social reputation and financial position. I knew that Vicente Guerrero had African roots, but I never thought about why it was important back then to have a black president. Now I understand because during those times in the Americas, people of color needed to be heard and understood. Guerrero gave freedom to the marginalized classes in Mexico because he identified himself with their issues, thus people identified with him and his policies, too. However, to me, those facts were part of understanding why he achieved what he did. It was not until I came to the United States, a culturally and socially different country when I found that race was crucial for determining who someone was. Then, I realized that perhaps things have not particularly changed. I support the idea that no matter the race we all can achieve what we desire if we have a purpose. Vicente Guerrero knew his purpose. He was a man of color, and as a Mexican, I am proud to say that he was the first black president in North America.

There were many reasons why people craved independence in New Spain, but most obvious was that nobody wanted to be controlled anymore. However, the issues were much more complex than that. People were tired of seeing the rich getting richer while the working class and the poor struggled to sustain their lives. They were eager to be able to decide what to do with their lives and be what they wanted but labeling based on skin color was a great limitation to their cause. The social classes largely depended on race and back then races were easily distinguished, with each race having a different standing in society. Mestizos, mulattoes, and other marginalized groups united to fight for their land, rights, and freedom in the independence movement to terminate the Spanish rule in New Spain. It was not until they rebelled against the Spanish that they had a voice.

This essay will detail the life of Vicente Guerrero, a Mexican independence leader, his fight for the liberty of his people and their homeland, which led to him being hailed as “Mexico’s greatest man of color.”

Slavery in New Spain

Vicente Ramon Guerrero Saldaña was born on August 9, 1783 in Tixtla, now the state of Guerrero in Mexico, to a humble family. His father, Juan Pedro Guerrero, was African- Mexican, while his mother, Guadalupe Saldaña, was a native Mexican. Vicente Guerrero did not have a formal education while growing up, but he dedicated his time to farming activities and working as an “arriero”, a mule driver that transports goods. Politically, both of his parents were devout supporters of the Spanish rule in New Spain.

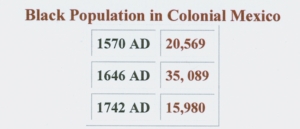

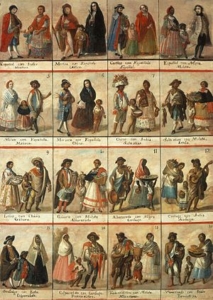

In the 16th century, New Spain likely had the largest number of African slaves of all the Americas. According to a 1595 census, Afro-Mexicans outnumbered Spanish and Mestizos (persons of indigenous and Spanish mixed-descent) in urban towns. By 1646, the numbers increased to 116,529 for Afro-Mexicans and 35,089 for those African identified. Clearly the number of children from mixed unions accounted for the much of the growth. African-descended populations thus comprised 8.8 percent, compared to Spaniards and their descendants, who comprised 0.8 percent in 1646. The New Spaniard society was not only constituted of Spanish, Indian, and African races as the mid-16th century saw Spaniards beginning to bring from their Pacific colony, Filipino slaves, as well as Chinese, Japanese, and Indian merchants. Therefore, New Spain began to get a great variety of mixed races that were each identified as a “casta” for instance: mestizos, mulattoes (Spanish and African), and moriscos (Spanish and Mulatto).

The colonies were a fundamental pillar for the development of European countries, by providing them with goods and a workforce, which helped countries to get richer and more powerful over European kingdoms. Historians have shown that many of the goods that Europeans craved such as gold, silver, and precious woods, foods like tomatoes, chocolate, corn, potatoes, and other products that Europeans did not have, were the fruits of enslaving people from places they had conquered.

Slavery had existed well before the discovery of the “New World”; however, the commerce of Africans became important for Europe only after the 15th century when they began to settle there and build colonies. The first Africans in New Spain accompanied explorers and conquistadors like Christopher Columbus and Hernan Cortes. Later enslaved Africans were taken to work in cotton fields or sugar plantations, cultivating coffee, tobacco, and rice, mining minerals, and other painful physical work. Gradually, blacks started to take roles previously performed by Mexican natives, whose population steadily declined from years of abuse from conquistadors, as well as the introduction of European diseases, such as smallpox, measles, influenza, pneumonia, typhus, cholera, and bubonic plague, brought by the Spaniards. It is estimated that 25 to 30 million West Africans were deported from their home countries and sold to different enslavers. Most of the enslaved were men, but also women and children were included. Combined, approximately 10 or 12 million slaves were brought to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries. In New Spain, there were only three ports in which Africans could be brought: Veracruz, Campeche, and Guerrero. From there, they would be transported and distributed to other areas of the country. Slavery lasted more than 300 years in New Spain until Vicente Guerrero abolished the practice in 1829, almost 40 years before President Abraham Lincoln would do the same in the United States when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Slavery had existed well before the discovery of the “New World”; however, the commerce of Africans became important for Europe only after the 15th century when they began to settle there and build colonies. The first Africans in New Spain accompanied explorers and conquistadors like Christopher Columbus and Hernan Cortes. Later enslaved Africans were taken to work in cotton fields or sugar plantations, cultivating coffee, tobacco, and rice, mining minerals, and other painful physical work. Gradually, blacks started to take roles previously performed by Mexican natives, whose population steadily declined from years of abuse from conquistadors, as well as the introduction of European diseases, such as smallpox, measles, influenza, pneumonia, typhus, cholera, and bubonic plague, brought by the Spaniards. It is estimated that 25 to 30 million West Africans were deported from their home countries and sold to different enslavers. Most of the enslaved were men, but also women and children were included. Combined, approximately 10 or 12 million slaves were brought to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries. In New Spain, there were only three ports in which Africans could be brought: Veracruz, Campeche, and Guerrero. From there, they would be transported and distributed to other areas of the country. Slavery lasted more than 300 years in New Spain until Vicente Guerrero abolished the practice in 1829, almost 40 years before President Abraham Lincoln would do the same in the United States when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

The numerical significance of these figures becomes clear when we compare them to the Spanish population of the colonial era. In the early colonial period, European immigration was extremely small–and for good reason. There were great risks and many uncertainties in the New World, and few families were willing to immigrate until some assurance of stability was demonstrated. Because of this hesitance, very few European women immigrated, thus preventing the natural growth of the Spanish population. The point that must be made here is the fact that the black population in the early colony was by far larger than that of the Spanish. In 1570 we see that the black population is about 3 times that of the Spanish. In 1646, it is about 2.5 times as large, and in 1742, blacks still outnumber the Spanish. It is not until 1810 that Spaniards are more numerous. (Source: Bobby Vaughn, “Blacks In Mexico — A Brief Overview”)

Guerrero’s rise to power

Vicente Guerrero’s journey as a national hero began while traveling as an “arriero” around New Spain and becoming familiar with the growing independence movement and meeting Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon, a leader of the rebellious movement. Guerrero started his military career in 1810 after meeting Morelos and participated in many important engagements, such as battles at Izucar and Taxco, first, under the command of insurgent leader Hermenegildo Galeana, then under Morelos. After Morelos was executed by a Spanish firing squad in 1815, Guerrero became the new Commander in Chief of the insurgent army. Guerrero became more powerful with every victory and in an effort to stop him, the Spaniards, in 1819, convinced his father to beg his son to offer his sword in surrender to the viceroy of New Spain. Instead, the younger Guerrero said defiantly, “Brothers, this old man is my father. He has come to offer me rewards in the name of the Spaniards. I have always respected my father, but my Motherland comes first.”

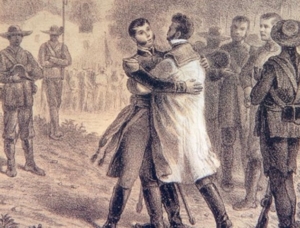

Even after losing a majority of his forces, the young Guerrero continued to fight in southern New Spain with only a handful of remaining insurgents. Even though Guerrero´s band was defeated, years of fighting took a heavy toll on the Spanish. On February 24, 1821, the leader of the Spanish forces, General Agustin de Iturbide, decided to make peace with Guerrero to stop the war that had lasted more than ten years. The two men met, and the agreement was sealed with the well-known “Abrazo de Acatempan” (The Acatempan Hug, because the two men’s embrace occurred in that city) on February 10, 1821 when both legions united to form the “Trigarante” army (the Army of Three Guarantees—religion, independence, and unity. Iturbide wrote the “El Plan de Iguala” on February 24 that declared Mexico as an independent and sovereign nation where the following points were established:

- New Spain, was no longer a Spanish dependent.

- Catholicism became the nation’s official religion.

- The unification of everyone despite their African, Mexican, Asian, or Spanish roots.

As an independent nation, New Spain became the Mexican Empire and its first emperor would be Agustin de Iturbide in 1822, though he ruled for only ten months because the empire was in an economic crisis and its problems were overwhelming with no further funding from Spain or other countries. Additionally, General Iturbide lacked the ability to lead the nation, and its people were not happy with the new government because its policies did not help the working and poor classes who were the most affected by the consequences of independence. However, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, who at the time was governor in Veracruz, recognized the problems and proclaimed Mexico as a Republic, and rose up against Iturbide. With the help of powerful generals like Nicolas Bravo, Guerrero, and Guadalupe Victoria, they fought for the people and defeated Iturbide who abdicated his position in March 1823.

After Iturbide stepped down, a Supreme Executive Power governed the nation and, Guerrero was an important member of that group. In 1824, a new Constitution proclaimed Guadalupe Victoria as the first president of Mexico. In 1829, when Victoria’s presidency was about to end, elections were held for his successor. The candidates were Guerrero, on the liberal side, and conservative candidate Manuel Gomez Pedraza, who was declared the winner. Guerrero’s supporters did not like the results and forced Gomez resign his presidency. On April 1, 1829 Guerrero became the second president of the republic.

A “casta” referred to the social stratum in which someone belonged according to his/her race or mixture of races in the Spanish colonies (New Spain and the Philippines). Each “casta” had a particular name depending on the race or mixture of races.

During his brief tenure, Guerrero managed to defend Mexico from an attempt by the Spanish to reconquer the nation. To defend his motherland, however, he exhausted the nation’s back up financial resources, which was met with disapproval from the country’s aristocracy. However, Guerrero made remarkable changes to support working classes, despite the serious economic limitations. He granted rights for indigenous peoples, fought for both racially and economically oppressed people, and promoted the purchase of Mexican products. His government was clearly dedicated to the people who had many needs after years and years of conflict that left the nation with a predominantly poor class.

On September 16, 1829, to celebrate the anniversary of independence with an act of justice, Guerrero formally abolished slavery in Mexico, except in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the south of the country. This monumental declaration, however, would lead to his downfall. Many people, especially the wealthy class, opposed his populist egalitarian idea, and even members of his administration opposed and betrayed him. More so, Euro-American enslavers, especially in Texas, did not like the idea of losing the economic power they had based on slavery. At the time, Texas was still part of the Republic of Mexico, and Guerrero’s order arrived in Texas October 16, but political chief Ramon Musquiz’ workers rejected it because it violated the colonization laws that secured the settlers properties. Unfortunately, Guerrero’s decree did not make any changes over slavery in Texas. This ultimately became a reason why Texas decided to secede from Mexico and join the United States, which still practiced slavery. After three months of his declaration, Guerrero was driven out of office. His own officials said that he did not possess the intellectual capacities to govern a nation, and he was forced to resign. Guerrero fled to southern Mexico, fearing for his life. However, Anastasio Bustamante, his vice president, ordered his assassination without a legal trial. On February 14, 1831, Gurrerro was found and killed at the age of 39 in Cuilapam, Oaxaca.

The phrase “My Motherland comes first” has proliferated over time and it reminds Mexicans that their independence was not given, it was needed, and their heroes fought for it, for their freedom. The state of Guerrero was named after Vicente Guerrero, and is the only state named after a former Mexican head of state. Guerrero, located in the Costa Chica region, is now home to one of several Afro-Mexican communities in Mexico.

Africans left their cultural expressions in Mexico, music, costumes, dances, and food, as well as their genetic imprint in states such as Veracruz, Tabasco, Michoacan, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. Although the race is blurry or difficult to identify thanks to the mixture of races throughout Mexican history, today there are many terms used by black Mexicans to identify themselves such as negro (black), moreno (dark), afrodescendiente, afromexicano, or blaxican, they self-identify as Afro-Mexicans. In 2020, one of the official ethnicity options on Mexico’s census form will be ‘negro’ (black), a great achievement by the black community in Mexico for having their African roots recognized. Mexican culture would not be the same today if Africans had not been brought there. Mexico would not be what it is if someone like Vicente Guerrero, a black man, had not fought for his land and his rights, which is why he has been called “Mexico’s greatest man of color.”

Africans left their cultural expressions in Mexico, music, costumes, dances, and food, as well as their genetic imprint in states such as Veracruz, Tabasco, Michoacan, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. Although the race is blurry or difficult to identify thanks to the mixture of races throughout Mexican history, today there are many terms used by black Mexicans to identify themselves such as negro (black), moreno (dark), afrodescendiente, afromexicano, or blaxican, they self-identify as Afro-Mexicans. In 2020, one of the official ethnicity options on Mexico’s census form will be ‘negro’ (black), a great achievement by the black community in Mexico for having their African roots recognized. Mexican culture would not be the same today if Africans had not been brought there. Mexico would not be what it is if someone like Vicente Guerrero, a black man, had not fought for his land and his rights, which is why he has been called “Mexico’s greatest man of color.”

References:

— Los Primeros Africanos en el Nuevo Mundo (The First Africans in the New World): http://www.omerfreixa.com.ar/los-esclavos-africanos-en-el-nuevo-mundo-todo-es-historia/

— The African-American Migration Story: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/on-african-american-migrations/

— ¿Cuando y Por Que Llegaron? (When and Why Did They Come?): https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/cuando-y-por-que-llegaron

— What Part of Africa Did Most Slaves Come From?: https://www.history.com/news/what-part-of-africa-did-most-slaves-come-from

— Transatlantic Slave Trade: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/slave-route/transatlantic-slave-trade/

— Transatlantic Slave Trade: https://www.britannica.com/topic/transatlantic-slave-trade#accordion-article-history

— Africa’s Legacy in Mexico: http://www.smithsonianeducation.org/migrations/legacy/almleg.html

— Vicente Guerrero: https://www.blackpast.org/aaw/vignette_aahw/guerrero-vicente-1783-1831/

— Vicente Guerrero: https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/vicente-guerrero

— Vicente Guerrero: The First Black President in North America: https://kentakepage.com/vicente-guerrero-the-first-black-president-in-north-america/

— Iturbide y La Independencia (Iturbide and The Independence): http://www.mexicanisimo.com.mx/iturbide-y-la-independencia/

— El Plan de Iguala (The “Plan de Iguala”): https://www.historiadelnuevomundo.com/index.php/2017/06/el-plan-de-iguala/

— Agustin de Iturbide, Primer Emperador de Mexico (Agustin de Iturbide, The First Emperor of Mexico): https://morelianas.com/articulos/agustin-de-iturbide-primer-emperador-de-mexico/

— El Fin del Imperio ¿Nacimiento de la Republica? (The End of The Empire. The Beginning of The Republic?): https://todoeshistoria.net/2012/03/19/el-fin-del-imperio-nacimiento-de-la-republica/

— Guadalupe Victoria Primer Presidente de Mexico (Guadalupe Victoria First President of Mexico): https://www.inside-mexico.com/guadalupe-victoria-primer-presidente-mexico/

— ¿Como Fue el Gobierno de Vincente Guerrero? (How was Vicente Guerrero’s Presidency?): https://www.lifeder.com/gobierno-vicente-guerrero/

— Vicente Guerrero The Black President of Mexico: http://www.saobserver.com/single-post/2018/01/23/Vicente-Guerrero-the-Black-President-of-Mexico

— The Untold History of Afro-Mexicans, Mexico’s Forgotten Ethnic Group: https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/mexico/articles/the-untold-history-of-afro-mexicans-mexicos-forgotten-ethnic-group/

— Guerrero Decree: https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ngg01