Wreck found by reporter may be last American slave ship, archaeologists say

Site of partially buried remains of the Clotilda alongside an island in the lower Mobile-Tensaw Delta near Mobile, Ala. Credit: Al.com.

(AL.com) Relying on historical records and accounts from old timers, AL.com may have located the long-lost wreck of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to bring human cargo to the United States.

What’s left of the ship lies partially buried in mud alongside an island in the lower Mobile-Tensaw Delta, a few miles north of the city of Mobile. The hull is tipped to the port side, which appears almost completely buried in mud. The entire length of the starboard side, however, is almost fully exposed. The wreck, which is normally underwater, was exposed during extreme low tides brought on by the same weather system that brought the “Bomb Cyclone” to the Eastern Seaboard. Low tide around Mobile was about two and a half feet below normal thanks to north winds that blew for days.

The Clotilda is the last ship known to have brought slaves into the country. The hunt for the ship has inspired numerous searchers over the years, but the Clotilda has long escaped discovery, until perhaps now. A small clarification for those familiar with the tale, the ship’s name is the Clotilda, not the Clotilde. Newspaper accounts beginning in 1860 misspelled the name, and over the years it stuck. But the ship’s license and the captain’s journal make clear that Clotilda is correct. (more)

“Clearing Stones” at the Austin History Center

(Austin Public Library) In honor of African American History Month, the Austin History Center unveils its newest exhibit Clearing Stones and Sowing Seeds: Photographs from the Travis County Negro Extension Service. The exhibit presents selections from the Travis County Negro Extension Service Photography Collection (AR.2000.025) archived at the History Center. The photographs, taken between 1940 and 1964, document the variety of services and educational programs offered by the Extension Service, including animal husbandry, crafts, domestic education, gardening and agriculture as well as home improvement. The exhibit will be on display from February 6 through April 15.

(Austin Public Library) In honor of African American History Month, the Austin History Center unveils its newest exhibit Clearing Stones and Sowing Seeds: Photographs from the Travis County Negro Extension Service. The exhibit presents selections from the Travis County Negro Extension Service Photography Collection (AR.2000.025) archived at the History Center. The photographs, taken between 1940 and 1964, document the variety of services and educational programs offered by the Extension Service, including animal husbandry, crafts, domestic education, gardening and agriculture as well as home improvement. The exhibit will be on display from February 6 through April 15.

About the Exhibit

Extension services in Texas officially began in 1915 when the Texas Legislature assigned administration of the Texas Agricultural Extension to Texas A&M University, and established the Cooperative Extension Program, administered by Prairie View A&M. As part of the Cooperative Extension Program, the Travis County Negro Extension Service served as the communication link between Prairie View A&M and Travis County Black residents. The agency provided assistance and programming to African American rural residents including Farm and Home Demonstrations. To acquaint young people with the latest in agricultural technology as well as build leadership and civic skills, the Extension Service created 4-H Clubs, providing services to African American rural youth.

Although the end of the age of segregation eliminated the need for dual governmental agencies, Prairie View A&M continues to oversee what was the Negro Extension Service program. The program has been modified to address the needs of customers with limited resources and is now called the Cooperative Extension Program. The photo exhibit Clearing Stones and Sowing Seeds provides an intimate glimpse into the lives of African American life in rural Travis County as documented by the Extension Service created to improve their lives.

The Austin History Center invites the public to the exhibit’s opening reception on Tuesday, February 6 at 6:30 PM. (more)

Meet the unheralded women who saved mothers’ lives and delivered babies before modern medicine

But that didn’t stop granny midwives from being demonized

W. Eugene Smith/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

(Timeline) Referred to as “granny midwives” (although there is some reason to believe they weren’t fans of the moniker), these lay health practitioners assisted pregnant women during labor and delivery. And for many poor and rural women, particularly in the South, granny midwives were lifesavers.

According to (a New York Times obit, one woman) delivered “virtually every child born in the predominantly black Mobile suburb of Prichard from 1931 to 1984.”

But midwives - the granny midwives of the South in particular - were repositories of knowledge that the state sought to control. Much has been made recently of the notion that women with expertise in healing practices have historically been persecuted. This awareness first peaked in the 1970s, as Second Wave feminists were learning about the ways female healers had been maligned, marginalized, and outright abused by the medical establishment.

In 1975, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English published their study Witches, Midwives, Nurses: A History of Women Healers. In it, they trace a centuries-long tradition of women in medicine, writing, “They were abortionists, nurses, and counselors. They were pharmacists, cultivating healing herbs and exchanging secrets of their uses. They were midwives, travelling from home to home and village to village. For centuries, women were doctors without degrees, barred from books and lectures, passing on experience from neighbor to neighbor and mother to daughter. They were called “wise women” by the people, witches or charlatans by the authorities. Medicine is part of our heritage as women, our history, our birthright.” (more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

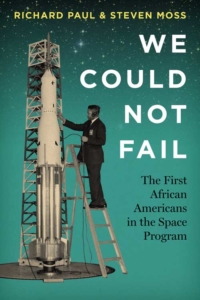

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “We Could Not Fail, The First African Americans in the Space Program,” by Richard Paul and Steven Moss.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page – including a featured selection – and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “We Could Not Fail, The First African Americans in the Space Program,” by Richard Paul and Steven Moss.

The Space Age began just as the struggle for civil rights forced Americans to confront the long and bitter legacy of slavery, discrimination, and violence against African Americans. Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson utilized the space program as an agent for social change, using federal equal employment opportunity laws to open workplaces at NASA and NASA contractors to African Americans while creating thousands of research and technology jobs in the Deep South to ameliorate poverty. We Could Not Fail tells the inspiring, largely unknown story of how shooting for the stars helped to overcome segregation on earth.

Richard Paul and Steven Moss profile ten pioneer African American space workers whose stories illustrate the role NASA and the space program played in promoting civil rights. They recount how these technicians, mathematicians, engineers, and an astronaut candidate surmounted barriers to move, in some cases literally, from the cotton fields to the launching pad. The authors vividly describe what it was like to be the sole African American in a NASA work group and how these brave and determined men also helped to transform Southern society by integrating colleges, patenting new inventions, holding elective office, and reviving and governing defunct towns. Adding new names to the roster of civil rights heroes and a new chapter to the story of space exploration, We Could Not Fail demonstrates how African Americans broke the color barrier by competing successfully at the highest level of American intellectual and technological achievement.

This Week in Texas Black History

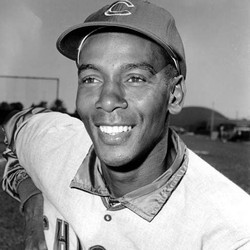

Ernie Banks

Jan31

On this date in 1931, Ernie Banks was born in Dallas. Banks attended Washington High School where he was a multi-sport star. He played with the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City Monarchs before becoming the first black player for the Major League Baseball Chicago Cubs. Known as “Mr. Cub,” Banks hit more home runs than anyone else in the majors from 1955 to 1960. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977.

Etta Moten

Jan31

On this date in 1934, Broadway and movie star Etta Moten (born in Weimar) sang for President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt at a White House dinner, marking the first time for an African-American woman to sing at the White House.

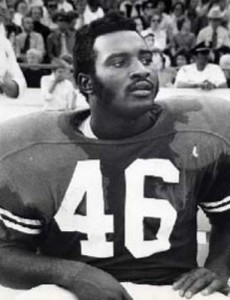

Roosevelt Leaks

Jan31

Roosevelt Leaks, the first African-American Texas Longhorns player to earn All-America honors, was born on this day in Brenham, TX, in 1953. Leaks rushed for 2,923 yards and 26 touchdowns in his three seasons at Texas. “Rosey” was a consensus All-America selection in 1973 and finished third that year in Heisman Trophy voting. He played nine seasons in the National Football League with the Baltimore Colts (1975-79) and Buffalo Bills (1980-83).

Joe Sample

Feb1

Jazz pianist great Joe Sample was born on this day in Houston in 1939. Sample, a graduate of Phillis Wheatley High School in 1956, teamed with Wheatley classmates Wayne Henderson (trombone), Wilton Felder (saxophone), and drummer Nesbert “Stix” Hooper to form the Jazz Crusaders in the 1960s and the group became wildly successful and critically acclaimed. Sample began playing piano at age 5, and at age 16 entered Texas Southern University and studied there for three years before the Jazz Crusaders left Houston for Los Angeles to begin the group’s phenomenal career. Sample was a leader or sideman on multiple gold and platinum albums and was popular as a studio musician, including for Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.”

Azie Taylor

Feb1

On this date in 1936, Azie Taylor was born in St. John Colony in Dale, Texas, near Austin. Taylor married James Homer Morton on May 29, 1965, and in 1977, President Jimmy Carter named her the 36th Treasurer of the United States for which she is still the only African-American to have held the position. She was a graduate of Huston-Tillotson University.

Dr. Bernard Harris, Jr.

Feb2

In 1995, on this date, Dr. Bernard Harris, Jr. became the first African-American to walk in space. A native of Temple, Texas, Harris was payload commander aboard Space Shuttle Discovery Mission STS-63, the first flight of the joint Russian-American Space Program. The main objective of the mission was to test systems and techniques to be used on later missions to dock with the Russian Space Station Mir.

Ernie Mae Miller

Feb2

On this date in 1927, musician Ernie Mae Miller was born in Austin. Miller was a graduate of L.C. Anderson High School, which was named for her grandfather. Miller played jazz, blues, gospel, and swing music and performed with the Prairie View Co-eds, a black, all-girl swing band from Texas that toured nationally during World War II. (See “Prairie View A&M University Coeds All Girl Band,” and “What if Jazz History Included the Prairie View Co-eds?” and the TIPHC Bookshelf for “Take-Off: American All-Girl Bands During World War II.”)

Feb3

On this day in 1870 the 15th amendment was ratified ensuring the right to vote to all male citizens of the United States, regardless of color or previous condition of servitude. The 15th Amendment opened the door for the elections of African-Americans to the U.S. Congress and to Southern local and state offices. Republicans wanted the 15th Amendment passed to obtain the vote of the freed slaves. However, many women suffragists had worked alongside Black suffragists like Frederick Douglass to gain the right to vote for both groups. However, when the 15th Amendment passed, it angered many women suffragists and some of them spoke out against Black suffrage. Women would not gain the right to vote until 1920.

Feb3

On this day in 1956, Irma Jean Sephas became first African American undergraduate student at North Texas State University. Sephas, 41, was from Fort Worth and majored in business with a music minor. She had previously attended Huston-Tillotson College in Austin.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, Ph.D., author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column addresses contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC staff welcome your comments.

Latest Entries

A New Hope

Forgive me for borrowing the title of one of the most profitable films in history, “Star Wars: A New Hope.” I’ve always been enamored by space. I’m a child of the 1960s and I remember playing with my Major Matt Mason action figure (not a doll!) as my family [...]

Tell me the truth

Democracy – a) government by the people, b) a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them, directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections. Merriam-Webster Dictionary There were many things I learned from my father. [...]

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments. Please contact Mr. Michael Hurd, Director of TIPHC, at mdhurd@pvamu.edu.