The long history of black voter suppression in American politics

(The Washington Post) In August 1922, the Topeka State Journal reported on an unusual voter suppression tactic. Members of the Ku Klux Klan reportedly flew over Oklahoma City, dropping cards into black neighborhoods warning people to be cautious before heading to the polls.

The only thing that’s really hard to believe about this is that the Klan used airplanes to deliver the message. It’s not surprising that anti-black rhetoric manifested itself in Oklahoma. The year prior, white mobs burned down a flourishing black community in Tulsa, killing an estimated 300 people.

The card-drop from the airplane was one thing. The Topeka State Journal also reported that Klansmen pledged to stake out polling places in Texas that year, with an aim to “take careful note of the voting procedure.” (This news article and the airplane one are via the excellent Tweets of Old Twitter account.)

Intimidation of voters by the Klan goes back way further than 1922, though. In 1871, Congress passed the Second Enforcement Act, better known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. Among its provisions was an effort to curtail often-violent efforts to prevent black people from casting votes in elections. Fifty years later, the Klan was no less subtle in its intentions, even if the methodology was sometimes — sometimes — more nuanced. (read more)

At 2 Georgetown Cemeteries, History in Black and White

Grave markers at Mount Zion. The cemetery is accessible through a littered parking lot behind an apartment building and known mostly to locals. Credit Lexey Swall for The New York Times

(New York Times) It is a tale of two cities of the dead. Two historic cemeteries lie side by side in Georgetown, separated by an overgrown dirt road, a rusting chain-link fence and two centuries of racial history.

On one side is Oak Hill, a lush slope of well-tended graves of congressmen, publishers and cabinet members who were, with few exceptions, white. On the other side is the Mount Zion and Female Union Band Society Cemetery. There, broken gravestones lie in large piles and dogs and their owners have taken the place of mourners for the slaves, freedmen and mostly black citizens buried below.

“There’s a quote: ‘Death reflects life, it’s not separate and apart,’” said Vincent deForest, a civil rights activist turned preservationist who has fought since the early 1970s to rescue Mount Zion. On a recent morning, to underscore the immortality of inequality, he stood in the black cemetery and pointed to the white cemetery.

“There,” he said, “we have a perfect reminder.”

Mr. deForest knows better than most. As the president of the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation, which promoted minority involvement in the 1976 bicentennial, and later as a special assistant to the director of the National Park Service, he helped put the cemetery and dozens of other sites of importance to African-Americans on the National Register of Historic Places, at a time when there were virtually none. (read more)

TIPHC Bookshelf

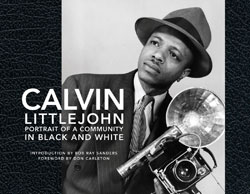

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Calvin Littlejohn, Portrait of a Community in Black and White,” by Bob Ray Sanders.

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer, “Calvin Littlejohn, Portrait of a Community in Black and White,” by Bob Ray Sanders.

In 1934, the year Calvin Littlejohn came to Fort Worth, the city was a sleepy little burg. This was the Jim Crow era, when mainstream newspapers wouldn’t publish pictures of black citizens and white photographers wouldn’t take pictures in black schools.

In Fort Worth, Littlejohn began what would become a lifelong career of documenting the black community. And there would be nothing remotely related to the white culture’s depictions of Amos ‘n’ Andy or black kids grinning over a slice of watermelon in Littlejohn’s portrayal of his adopted home and the people he came to appreciate and love. Littlejohn’s natural aptitude for drawing had been honed by correspondence courses in graphic design and a stint in a photo shop where he learned about the camera, lighting, and the use of shadows.

When Littlejohn was assigned to be the official photographer at I. M. Terrell—the city’s only black high school at the time—his professional career was launched.

Unlike many segregated cities, where blacks lived only in one section, blacks in Cowtown lived in every quadrant of the city. There was a thriving black business district, with hotels, restaurants, a movie theater, a bank, and a major hospital, pharmacy, and nursing school. And of course, there were the schools and churches. All would eventually be seen through Littlejohn’s lens.

Although he never set out to be the documentarian of Fort Worth’s black community, he did what he set out to do: to capture the best of a community, focusing on its good times.

This book features more than 150 shots Littlejohn captured over the course of his career.

This Week In Texas Black History, Oct. 30-Nov. 5

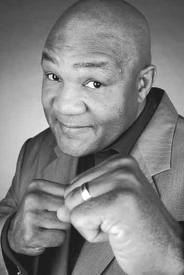

30 — On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy — leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

30 — On this day in 1974, Houston’s George Foreman, heavyweight champion, lost his title to Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was favored to win, but in the second round, Ali began his “rope-a-dope” strategy — leaning against the ropes while shielding his head and absorbing body blows from Foreman. As Ali continued the tactic, Foreman tired and his punches lost power and in the eighth round a visibly fatigued Foreman was knocked down for the first time in his career and counted out suffering his first defeat. Years later, Foreman would say, “The day after I lost to Ali, people came by and put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘It’s okay, George. You’ll have another chance.’ That was pity. (I went) from being feared to being pitied. Brother, that’s a long fall.”

30 – On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

30 – On this day in 1892, Clifton Richardson was born in Marshall, Texas. Richardson became founder (in 1919), editor and publisher of the Houston Informer. In 1930, he had the same roles with the Houston Defender. Richardson was also a vocal supporter of civil rights and a founding member of the Civic Betterment League (CBL) of Harris County and founding member and later president of Houston’s NAACP chapter.

31 — On this day in 1835 a volunteer company was formed in Huntsville, Ala. to travel to Texas and help fight in the Texas Revolution against Mexico. A free black, Peter Allen, a flutist, was welcomed into the company as a musician. Allen, a native of Philadelphia, Pa. was the son of Richard Allen, founder and first Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. On March 20, 1836, Allen and his company, approximately 300 men commanded by Col. James Walker Fannin, participated in the Battle of Coleto Creek, but the men were forced to surrender and were imprisoned at Goliad. A week later, on Palm Sunday, all of the men were executed and their bodies burned in what became known as the Goliad Massacre. Asked by the Mexican commander to play a tune in exchange for his freedom, Allen refused and was also executed. Reportedly, Allen had responded to the request by saying, “No, I’ll not play, but I’ll just go along with the rest of the boys.”

31 — State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

31 — State Senator George T. Ruby died of malaria in New Orleans on this day in 1882. Ruby had been an agent for the Freedman’s Bureau administering its schools for former slaves. In 1868 he was the only black delegate from Texas at the National Republican Convention and also was one of 10 African American delegates to Texas Constitutional Convention of 1868-69. As a senator in the 12th Legislature Ruby was appointed to the Judiciary, Militia, Education, and State Affairs committees. He introduced successful bills to incorporate Texas railroads and a number of insurance companies and to provide for the geological and agricultural survey of the state. He was called “one of the most influential men of the 12th and 13th Legislatures,” and one of the “most prominent black politicians of Reconstruction.”

31 — Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

31 — Kenneth Sims was born on this day in 1959 in Kosse, Texas. Sims, a defensive end, would become the first member of the University of Texas football program to win the Lombardi Award, presented to college football’s best lineman. Sims won the award as a senior, in 1981, and was taken No. 1 overall in the 1982 National Football League draft by the New England Patriots. He played eight years in the NFL.

November

1 – In 1903, on this day, Houston music impresario Don Robey was born. Robey was influential in developing the Texas blues scene, but he also produced major gospel talents. Robey’s music business empire included several music labels, most prominent being Peacock Records, and his was likely the first such enterprise run by an African-American. Robey produced dozens of blues and gospel artists, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Mighty Clouds of Joy.

1 – In 1903, on this day, Houston music impresario Don Robey was born. Robey was influential in developing the Texas blues scene, but he also produced major gospel talents. Robey’s music business empire included several music labels, most prominent being Peacock Records, and his was likely the first such enterprise run by an African-American. Robey produced dozens of blues and gospel artists, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Memphis Slim, Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton, the Dixie Hummingbirds, and the Mighty Clouds of Joy.

2 — On this day in 1963, the Baylor University Board of Trustees voted to integrate the school, the world’s largest Baptist institution of higher learning. Hilton E. Howell, chairman of the board, said, “The action of the Baylor University Board of Trustees was taken after full and free discussion. While the final vote of the board adopting the new policy was not unanimous, the decision was reached by amicable discussion and democratic procedure.”

2 — On this day in 1963, the Baylor University Board of Trustees voted to integrate the school, the world’s largest Baptist institution of higher learning. Hilton E. Howell, chairman of the board, said, “The action of the Baylor University Board of Trustees was taken after full and free discussion. While the final vote of the board adopting the new policy was not unanimous, the decision was reached by amicable discussion and democratic procedure.”

2 – On this day in 1999, legendary Prairie View A&M football coach Billy Nicks passed away in Houston at age 94. Nicks was a native of Griffin, Ga. and attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. As a coach, his 1941 Morris Brown team was named black college national champion, but it would be in Texas, at Prairie View, where Nicks would make his mark as one of the top coaches in college football history. He began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC opponent, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. Nicks’ overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. He is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

2 – On this day in 1999, legendary Prairie View A&M football coach Billy Nicks passed away in Houston at age 94. Nicks was a native of Griffin, Ga. and attended Morris Brown College in Atlanta where he played football, basketball, baseball, and ran track. As a coach, his 1941 Morris Brown team was named black college national champion, but it would be in Texas, at Prairie View, where Nicks would make his mark as one of the top coaches in college football history. He began coaching at Prairie View in 1945 and in 17 years compiled a 127-39-8 record and won eight Southwestern Athletic Conference championships and five black college national championships. He had five undefeated seasons as Prairie View became a black college football power in the 1950s and 1960s. Nicks had a winning record against every SWAC opponent, including Grambling State and legendary head coach Eddie Robinson. Nicks’ overall record, for 28 years, was 193-61-21, a winning percentage of .763. He is a member of numerous halls of fame, including the College Football Hall of Fame, NAIA, and the SWAC.

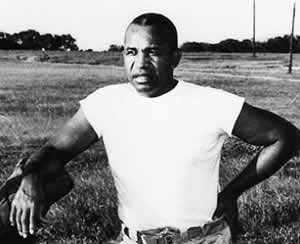

3 – Matthew “Bones” Hooks was born on this day in 1867 to former slave parents in Robertson County, Texas. Hooks was a cowboy and legendary horse breaker, who was also one of the first black cowboys to work alongside whites as a ranch hand. He later became a civic leader and worked with youth groups in Amarillo.

3 – Matthew “Bones” Hooks was born on this day in 1867 to former slave parents in Robertson County, Texas. Hooks was a cowboy and legendary horse breaker, who was also one of the first black cowboys to work alongside whites as a ranch hand. He later became a civic leader and worked with youth groups in Amarillo.

5 – On this day in 1901, actress and singer Etta Moten was born in Weimar, Texas. Moten was touted as the “new Negro woman” for her ground-breaking movie roles. She married Claude Barnett, founder of the Associated Negro Press in 1934 the same year, she became first black woman to sing at the White House when she performed for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s birthday celebration. For the production of “Porgy and Bess,” Broadway composer George Gershwin wrote the female lead character with Barnett in mind.

5 – On this day in 1901, actress and singer Etta Moten was born in Weimar, Texas. Moten was touted as the “new Negro woman” for her ground-breaking movie roles. She married Claude Barnett, founder of the Associated Negro Press in 1934 the same year, she became first black woman to sing at the White House when she performed for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s birthday celebration. For the production of “Porgy and Bess,” Broadway composer George Gershwin wrote the female lead character with Barnett in mind.

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Breaking my promise” Read it

Ron Goodwin’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. His latest blog is, “Breaking my promise” Read it

Submissions Wanted

Historians, scholars, students, lend us your…writings. Help us produce the most comprehensive documentation ever undertaken for the African American experience in Texas. We encourage you to contribute items about people, places, events, issues, politics/legislation, sports, entertainment, religion, etc., as general entries or essays. Our documentation is wide-ranging and diverse, and you may research and write about the subject of your interest or, to start, please consult our list of suggested biographical entries and see submission guidelines. However, all topics must be approved by TIPHC/TBHPP editors before beginning your research/writing.

We welcome your questions or comments via email or telephone – mdhurd@pvamu.edu.