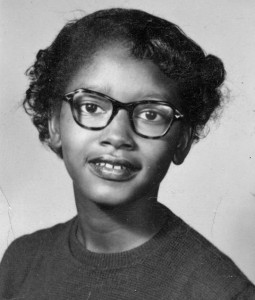

Claudette Colvin: Before Rosa Parks

President Barack Obama hailed Civil Rights pioneer Rosa Parks on Monday as a “giant of her age,” on the 60th anniversary of her arrest in Montgomery, Ala. for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man. Parks’ action led to a boycott of the city’s public transportation system and ignited the Civil Rights Movement.

President Barack Obama hailed Civil Rights pioneer Rosa Parks on Monday as a “giant of her age,” on the 60th anniversary of her arrest in Montgomery, Ala. for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man. Parks’ action led to a boycott of the city’s public transportation system and ignited the Civil Rights Movement.

However, nine months earlier, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested for the same thing, but her ordeal had none of the effect as Parks’.

After school on March 2, 1955, Colvin walked to downtown Montgomery with three of her classmates. She and her friends were going to take the city bus home from school that day. When they boarded the bus, they sat behind the first five rows, which were reserved for white passengers. A young white woman boarded the bus after Colvin and her friends and found nowhere to sit because the white section was full. Bus drivers had the authority to make black passengers move for white passengers, even if they were sitting in the black section. The bus driver asked Colvin and her friends to get up, which her friends immediately did. She refused to move and police were called.

Later, Colvin said: “I could not move because history had me glued to the seat…Sojourner Truth’s hands were pushing me down on one shoulder and Harriet Tubman’s hands were pushing me down on another shoulder.” The police officers each grabbed one of her arms, kicked her, threw her books from her lap, and “manhandled” her off the bus. They shoved her in their police car, handcuffed her through the windows, and took her off to jail. She was the first person to be arrested for challenging Montgomery’s bus segregation laws.

Read the details of her courageous stand, its aftermath, and thoughts on why her actions had no significant impact on the Civil Rights Movement.

Holiday baking: How sweet potato pie became African Americans’ Thanksgiving dessert

Adrian Miller is an award-winning author and “soul food scholar,” and for the holiday baking season, beginning last week, he examines the surprising history of a favorite African American dessert — sweet potato pie.

author and “soul food scholar,” and for the holiday baking season, beginning last week, he examines the surprising history of a favorite African American dessert — sweet potato pie.

Read his story for The Washington Post in which Miller says: “For millions of African Americans like me, Thanksgiving Day means sweet potatoes, not pumpkins, and we love sweet potatoes so much that we won’t settle for having a sole side dish of candied sweet potatoes (we call them “yams,” but that’s another story) or sweet potato casserole. No, we have to double down on this tasty tuber and serve up sweet potato pie for dessert, too. Sure, we eat this soul food classic year-round, but this is the week that the sweet potato pie really shines. It doesn’t have to be the only dessert option on the holiday table, but it has to at least be part of the lineup. Otherwise, at least in African American households, the spread is immediately suspect.

“As much as sweet potato pie is beloved within the black community and in the South, it doesn’t seem to get much love elsewhere. Our national pie divide is deepest when people choose between pumpkin pie and sweet potato pie on Thanksgiving Day. And that got me wondering: How did sweet potato pie become a soul-food favorite over its chief Thanksgiving rival? It started happening centuries ago, and it didn’t follow the path that you might expect.”

Miller is also a culinary historian and a certified barbecue judge who has lectured around the country on such topics as: Black Chefs in the White House, chicken and waffles, hot sauce, kosher soul food, red drinks, soda pop, and soul food. His book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time was published by the University of North Carolina Press in August 2013 and won the 2014 James Beard Foundation Book Award for Reference and Scholarship.

Roundtable: The Age of Garvey, How a Jamaican Activist Created a Mass Movement and Changed Global Politics

From November 23-30, the African American Intellectual History Society hosted an online roundtable on Adam Ewing’s The Age of Garvey: How a Jamaican Activist Created a Mass Movement and Changed Global Politics (Princeton University Press, 2014). Several scholars offered reviews of the book and Ewing responded on the final day. Read the entries here.

From November 23-30, the African American Intellectual History Society hosted an online roundtable on Adam Ewing’s The Age of Garvey: How a Jamaican Activist Created a Mass Movement and Changed Global Politics (Princeton University Press, 2014). Several scholars offered reviews of the book and Ewing responded on the final day. Read the entries here.

“This forum is a good example of the ways in which scholarly collaboration can lead to important scholarly work, which can open new vistas of thought and engagement,” said roundtable moderator Stephen G. Hall, Assistant Professor of History at Alcorn State University. “At a very early stage of working on my current book project, “Global Visions: African American Historians Engage the World, 1885-1960,” I was casting about trying to think more broadly about the intersections between historical production and global organizational activism in the Diaspora. I had the good fortune to read portions of Keisha Blain’s dissertation at Princeton and stumbled upon references to Adam Ewing’s dissertation at Harvard titled “Broadcast on the Winds: Diasporic Politics in the Age of Garvey, 1919-1940” (2011). After reading the dissertation in its entirety, I recognized immediately its importance as a model for the complex shape that Diasporic politics could take in Africa, the African Diaspora and beyond. When I broached the idea of this forum to Keisha Blain, it seemed as though we were similarly and singularly convinced of its importance and the idea took root and blossomed into the current forum.”

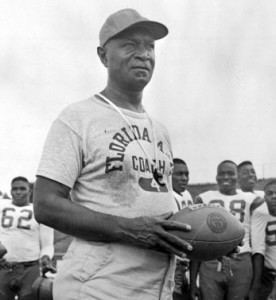

College Football’s Real Racial Breakthrough Was FAMU vs. Tampa, 1969

For the 46th anniversary of the groundbreaking football game between Florida A&M and the University of Tampa, New York Times writer Samuel Freedman revives an article he wrote several years ago, adapted from his book Breaking The Line, The Season in Black College Football That Transformed the Sport and Changed the Course of Civil Rights.

For the 46th anniversary of the groundbreaking football game between Florida A&M and the University of Tampa, New York Times writer Samuel Freedman revives an article he wrote several years ago, adapted from his book Breaking The Line, The Season in Black College Football That Transformed the Sport and Changed the Course of Civil Rights.

Freedman: “On November 29, 1969, one of the most significant events in the history of sports and the Civil Rights Movement occurred in Tampa, Fla. when an HBCU football team played a predominantly white team in the South for the first time ever. Contrary to racist presumptions about white supremacy on the gridiron, as everywhere else, all-black Florida A&M coached by Jake Gaither defeated the University of Tampa 34-28. The game became the largest act of mass desegregation of a public facility in American history, with a racially mixed crowd of 45,000 at Tampa Stadium. More than anything else in Gaither’s storied career at FAMU, this barrier-breaking game was his gift to the country he loved — even as that country all too often refused to reciprocate. Many fans and sportswriters consider the key game in desegregating college football was Alabama vs. USC in 1970, when Trojans’ running back Sam Cunningham, an African American, led a resounding defeat of the Crimson Tide, 42-21, in Birmingham, prompting its coach, Paul “Bear” Bryant to swear he would begin recruiting black players. (Ed. Note: Reportedly, Bryant said, “I got to get me some of them (black players).” Yet, that game was a year after FAMU-Tampa! Actually, Bryant had already been sued by civil rights attorneys for his longtime refusal to recruit African-American student-athletes.”

Read Freedman’s piece here.

Guy Lewis, 1922-2015: Univ. of Houston basketball coach helped integrate Southern college hoops

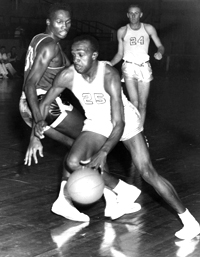

Lewis, center, with Elvin Hayes (left) and Don Chaney

Guy Lewis, Hall of Fame basketball coach known for leading the University of Houston’s Phi Slama Jama teams of the early 1980s, died on Thursday at a retirement home in Kyle, Tex. He was 93.

Beyond his many honors and on-the-court accomplishments, Lewis helped integrate college basketball in the South by signing the Houston program’s first African-American players, Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney. The pair were among 30 of Lewis’s players who ascended to the N.B.A., with Hakeem Olajuwon, like Hayes, becoming a No. 1 overall draft pick.

Officials at the University of Houston announced his death in a statement.

“Without the presence of Lewis, the history of the University of Houston would have been drastically different,” university officials wrote in his biography on the Houston athletics website. “His tremendous impact here and on the game will be remembered across the nation.”

Read the New York Times obit.

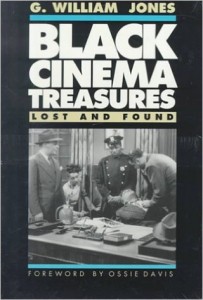

TBHPP Bookshelf

Published scholarship on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer “Black Cinema Treasures,” by G. William Jones, with a foreword by Ossie Davis. Focusing on a much-neglected area of film experience in America, “Black Cinema Treasures” furthers the preservation of America’s cultural and historic heritage, especially its African-American heritage, as seen through the eyes of the African-American independent filmmakers of the 1920s through the 1950s.

on black history in Texas is growing and we’d like to share with you some suggested readings, both current and past, from some of the preeminent history scholars in Texas and beyond. We invite you to take a look at our bookshelf page — including a featured selection — and check back as the list grows. A different selection will be featured each week. We welcome suggestions and reviews. This week, we offer “Black Cinema Treasures,” by G. William Jones, with a foreword by Ossie Davis. Focusing on a much-neglected area of film experience in America, “Black Cinema Treasures” furthers the preservation of America’s cultural and historic heritage, especially its African-American heritage, as seen through the eyes of the African-American independent filmmakers of the 1920s through the 1950s.

This Week In Texas Black History, Nov. 29-Dec. 5

Calendar courtesy Texas Black History Preservation Project

1 – On this day in 1989 dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey died in New York City of blood dyscrasia. Ailey, a native of Rogers, Texas, founded his namesake dance theater in 1958. Ailey made his Broadway debut in 1954 and in 1958 gained his first critical success for his choreography for Blues Suite, which also marked the beginning of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. His troupe, in 1970, became the first American dance company to tour the USSR in 50 years and received a 20-minute ovation for their performance in Leningrad.

1 – On this day in 1989 dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey died in New York City of blood dyscrasia. Ailey, a native of Rogers, Texas, founded his namesake dance theater in 1958. Ailey made his Broadway debut in 1954 and in 1958 gained his first critical success for his choreography for Blues Suite, which also marked the beginning of the Alvin Ailey Dance Company. His troupe, in 1970, became the first American dance company to tour the USSR in 50 years and received a 20-minute ovation for their performance in Leningrad.

1 – On this day in 1956, Charles Brown became the first black athlete to participate in a major college sport in Texas when he suited up for Texas Western College (now Univ. of Texas at El Paso), 10 years before John Westbrook at Baylor and Jerry LeVias at Southern Methodist University broke the color line for the Southwest Conference in September 1966. Brown had attended predominantly black Douglass High School in El Paso, served in the Air Force during the Korean War then attended Amarillo Junior College before he and his nephew, Cecil, joined Texas Western. In his debut, Brown scored 16 points and, according to the El Paso Times, “dazzled the crowd” as the Miners beat New Mexico Western 73-48. Though only 6-foot-1, from 1956-1959, Brown led the Border Conference in scoring and rebounding. He concluded his career with 1,170 points and 578 rebounds, averaging 17.5 points and 8.6 rebounds. Brown was inducted into the El Paso Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999 and the UTEP Athletic Hall of Fame in 2008. On March 2, 2011, UTEP hung Brown’s jersey No. 25 in the rafters. On Sunday, May 11, 2014, Brown passed away in Antioch, California at the age of 83.

1 – On this day in 1956, Charles Brown became the first black athlete to participate in a major college sport in Texas when he suited up for Texas Western College (now Univ. of Texas at El Paso), 10 years before John Westbrook at Baylor and Jerry LeVias at Southern Methodist University broke the color line for the Southwest Conference in September 1966. Brown had attended predominantly black Douglass High School in El Paso, served in the Air Force during the Korean War then attended Amarillo Junior College before he and his nephew, Cecil, joined Texas Western. In his debut, Brown scored 16 points and, according to the El Paso Times, “dazzled the crowd” as the Miners beat New Mexico Western 73-48. Though only 6-foot-1, from 1956-1959, Brown led the Border Conference in scoring and rebounding. He concluded his career with 1,170 points and 578 rebounds, averaging 17.5 points and 8.6 rebounds. Brown was inducted into the El Paso Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999 and the UTEP Athletic Hall of Fame in 2008. On March 2, 2011, UTEP hung Brown’s jersey No. 25 in the rafters. On Sunday, May 11, 2014, Brown passed away in Antioch, California at the age of 83.

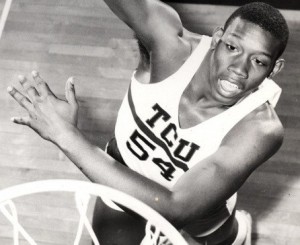

1 – James Cash becomes the first African American to play basketball in the Southwest Conference on this day in 1966 when Texas Christian University opened its season at Oklahoma, losing 90-76. Cash had starred at Fort Worth I.M. Terrell High School playing for legendary coach Robert Hughes. Cash graduated from Terrell in 1965, but because of the NCAA’s freshmen ineligible rule, would not take the court for TCU until 1966. In his first season, 1966-67, Cash started at forward and averaged 11.5 points, and led the team in rebounds with 266. The team would finish the season 10-14 overall, 8-6 in the SWC (second place). However, Cash would help lead the team to a conference championship and NCAA Tournament (first round loss) the next season. An Academic All-American, Cash received a degree in math and later a master’s and Ph.D. from Purdue University and would become a full-time professor and then Dean of the MBA Program at the Harvard Business School (and the school’s first tenured black professor). Cash served on various corporate boards including Microsoft, General Electric, and Wal-Mart and became part owner of the NBA Boston Celtics.

1 – James Cash becomes the first African American to play basketball in the Southwest Conference on this day in 1966 when Texas Christian University opened its season at Oklahoma, losing 90-76. Cash had starred at Fort Worth I.M. Terrell High School playing for legendary coach Robert Hughes. Cash graduated from Terrell in 1965, but because of the NCAA’s freshmen ineligible rule, would not take the court for TCU until 1966. In his first season, 1966-67, Cash started at forward and averaged 11.5 points, and led the team in rebounds with 266. The team would finish the season 10-14 overall, 8-6 in the SWC (second place). However, Cash would help lead the team to a conference championship and NCAA Tournament (first round loss) the next season. An Academic All-American, Cash received a degree in math and later a master’s and Ph.D. from Purdue University and would become a full-time professor and then Dean of the MBA Program at the Harvard Business School (and the school’s first tenured black professor). Cash served on various corporate boards including Microsoft, General Electric, and Wal-Mart and became part owner of the NBA Boston Celtics.

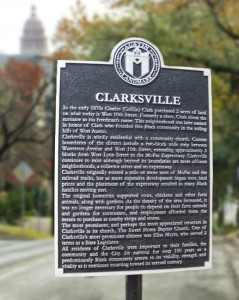

1 – On this day in 1976, the Clarksville neighborhood in Austin was added to National Register of Historic Places. Clarksville was originally the location of slave quarters for a plantation outside of Austin owned by Texas Governor Elisha M. Pease who gave the land to his emancipated slaves. Freedman Charles Clark established the community in 1871 and subdivided the land among other freedmen.

1 – On this day in 1976, the Clarksville neighborhood in Austin was added to National Register of Historic Places. Clarksville was originally the location of slave quarters for a plantation outside of Austin owned by Texas Governor Elisha M. Pease who gave the land to his emancipated slaves. Freedman Charles Clark established the community in 1871 and subdivided the land among other freedmen.

5 – On this day in 1972, Austin musician Kenny Dorham died of kidney failure at age 48 in New York City. Dorham was one of the great trumpet pioneers of the bebop era, and worked with many of the bebop giants in the ’40s and ’50s, including Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, and Thelonius Monk.

5 – On this day in 1972, Austin musician Kenny Dorham died of kidney failure at age 48 in New York City. Dorham was one of the great trumpet pioneers of the bebop era, and worked with many of the bebop giants in the ’40s and ’50s, including Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine, Lionel Hampton, and Thelonius Monk.

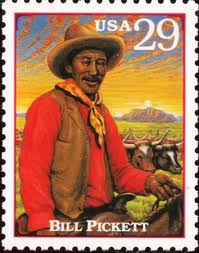

5 – Willie M. “Bill” Pickett, the cowboy known as the “Dusky Demon” and inventor of the rodeo sport of bulldogging (steer wrestling), was born on this day in 1870 in Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, Pickett was the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

5 – Willie M. “Bill” Pickett, the cowboy known as the “Dusky Demon” and inventor of the rodeo sport of bulldogging (steer wrestling), was born on this day in 1870 in Taylor, northeast of Austin. In 1971, Pickett was the first black man elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma. In 1993, the U.S. Postal Service honored him as part of its Legends of the West series of stamps.

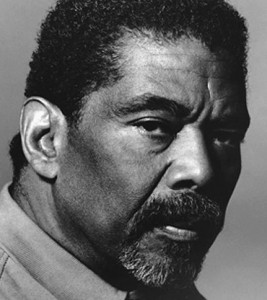

Blog: Ron Goodwin, author, PVAMU history professor

Ron Good  win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. In his latest blog, “Art imitating life(?),” Goodwin draws parallels between the movie “The Hunger Games” and real life scenarios where the poor serve as entertainment for the wealthy as a way of escaping sometimes dire consequences, especially in the black community. Read it

win’s bi-weekly blog appears exclusively for TIPHC/TBHPP. Goodwin is a San Antonio native and Air Force veteran. Generally, his column will address contemporary issues in the black community and how they relate to black history. He and the TIPHC/TBHPP staff welcome your comments. In his latest blog, “Art imitating life(?),” Goodwin draws parallels between the movie “The Hunger Games” and real life scenarios where the poor serve as entertainment for the wealthy as a way of escaping sometimes dire consequences, especially in the black community. Read it