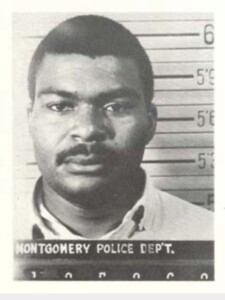

Wendell Paris was just 16 when he was arrested for trespassing—simply for driving through a state park in Alabama. At the time, Black people were not allowed there. He and his lifelong friend Sammy Younge were both taken into custody. Paris grew up in Tuskegee, where he became a leader in the student-run Tuskegee Advancement League.

Larry Rubin, the child of union organizers in Philadelphia, met Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader Chuck McDew in the dining hall at Antioch College, where McDew was visiting his girlfriend. Encouraged by McDew, Rubin soon made his way south. He was arrested for the first time at age 18.

Both men became active in the SNCC, an organization of students who lived and worked alongside local people to transform their communities—and, ultimately, the world. Every student-led movement since has drawn on their tactics as a blueprint and their courage as a wellspring of inspiration.

Now elders, Paris and Rubin are part of the SNCC Legacy Project, an effort to preserve the stories of SNCC veterans and continue the pursuit of justice. The project organizes reunions, supports voter education, and teaches students about the Civil Rights Movement. More than that, these activists embody what it means to dedicate a life to humanity. Simply sitting with them is a lesson in itself.

Prairie View A&M University students were not members of SNCC, but they organized and took action during the movement. In the 1960s, students protested and boycotted businesses in nearby Hempstead that refused to serve Black customers. They also called on university leadership to address the unequal treatment of Black students and the institution itself.

In 1963, students organized a successful boycott of homecoming. The Panther, the student newspaper, reported that both students and alumni canceled all homecoming festivities in solidarity. Even Miss Prairie View declined to participate in the annual coronation ceremony. Fewer than 100 people attended the homecoming football game, most of them parents of players. Meanwhile, nearly 2,000 people rallied for civil rights in front of the student center.

This spring, the SNCC Legacy Project came to PVAMU as the third Activist-in-Residence at the Ruth J. Simmons Center for Race and Justice. Over the course of two days, they met with students in classes, sharing their stories with young people the same age they were when they began to reshape America.

They urged students to honor the humanity of others. They spoke about American history, discussed the value of cooperative farming with agriculture majors, and debated protest philosophies in a class on Gandhi and King. They helped students returning from the Civil Rights Bus Tour process what they had seen and learned. They visited the University farm, met with scientists and workers, and brought energy and generosity to every encounter.

They encouraged students to connect with each other and challenged the idea that activists always agree—or always know how things will turn out. They spoke candidly about their proudest and most difficult days in the movement, offering vulnerable, honest accounts of the risks and rewards of political activism.

Students stayed after class to thank them and offer hugs. Faculty and staff reflected on how to build a lasting relationship with the SNCC Legacy Project. Provost Emerita Johanna Thomas-Smith, who attended Tuskegee a few years after Mr. Paris, shared stories with him while students eagerly asked questions.

Our visitors said they could have stayed longer and that they were invigorated by our students.

There’s no way to fully describe what this experience meant to me. I’ve taught this history and read about it. But to sit with these individuals—personal heroes—is something else entirely. Who needs Superman and Batman when you have Wendell Paris and Larry Rubin?

They arrived on our campus as strangers. They left as family.

The SNCC Legacy Project is an effort by members of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee to preserve and collect their history, develop a digital archive of events, oral histories and documents and motivate others by bringing their work alive for future generations. They work with scholars and student groups to keep their history alive and inspire others through their work. They also engage in critical conversations about how their work in the 1960s can inform our understanding of the world today.

Dr. Melanye T. Price ’95 is an Endowed Professor of Political Science and Director of the Ruth J. Simmons Center for Race and Justice at Prairie View A&M University.