“The idea of expressing the historical development of the Negro through the dance medium came to me over a year ago,” recalled George Ruble Woolfolk, an up-and-coming history professor at Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical (A&M) College in the March 1946 edition of the student newspaper, the Panther. “This is interpretative dancing and is designed to symbolize the advancement of the Negro from Africa to the present day.” The artistic performance, Woolfolk added, had “three major groups.” Beginning with the enslavement period, the presentation next turned watchers attention to the African American experience regarding city living that followed slavery’s abolishment. “The third set portrays the participation of the Negro in the wars of the Nations,” explained Woolfolk, who obtained his Ph.D. in history from the University of Wisconsin a year later in 1947 and who also went on to have a long and illustrious career with Prairie View A&M College that extended from the 1940s to the 1980s. Yet, while Professor Woolfolk conveyed the central themes of the artistic presentation connected to Prairie View A&M’s “Negro History Week,” he additionally noted its important finale. In short, the performance concluded by stressing the ongoing essentiality concerning African Americans being “race conscious in our national democracy.”[1]

In honor of Black History Month 2022, this essay focuses on Professor George Ruble Woolfolk and some of his involvements over the decades with facilitating Negro History Week programming at Prairie View A&M College. Beginning in early February 1926, historian Carter G. Woodson commenced Negro History Week to bring both an awareness and consciousness of the historical contributions of people of African descent. As a result of Woodson’s scholarly activism, numerous other African American intellectuals followed the lead of “the Father of Black History” in the ensuing decades.[2]

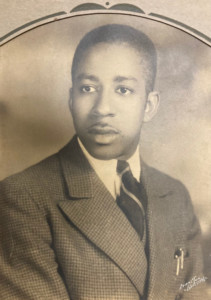

Woolfolk was one of them. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, the future professor—and prolific scholar of African American history in his own right—was born, remarkably, during the same month of February (1915) that Woodson selected over a decade later to promulgate Black history to the world. Eventually, the Black Kentuckian graduated in 1937 from Louisville Municipal College for Negroes during the latter stages of the Great Depression with his B.A; Woolfolk matriculated into the Ohio State University, where he obtained his first advanced degree (M.A.) the next year (1938). Then, during the middle (1943) of United States involvement in World War II, Woolfolk started his long and impactful history career with Prairie View A&M College. He did so, however, some four years before (1947) he took his doctorate in history, working under William B. Hesseltine, an esteemed scholar of the American Civil War.[3]

The database Digital Commons@PVAMU: A Repository of Archives, Research & Scholarship offers a wealth of primary material relating to the history of Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU). Held within the Digital Commons@PVAMU is also a treasure trove of illuminating and insightful evidence documenting Woolfolk and his direct involvement with Prairie View A&M’s Negro History Week program over the years. In sum, Woolfolk’s ties to Negro History Week programming launched early on during his extensive tenure on “The Hill” and only continued in the decades that followed. A few examples will suffice.[4]

Like the dancing performance published in the March 1946 edition of the Panther, which captured the Black experience from a unique artistic perspective, three years later, Woolfolk weaponized the vehicle of art to convey Black history. Honoring “National Negro History Week February 6-13,” the Panther publication from March 1949 featured Woolfolk, as well as a pupil named Hilliard George Lewis. They transmitted their collaborative artistic work, however, via radio during “the regular Sunday night broadcast, ‘Prairie View Serves Texas’ over Station KLEE at 10:30 P.M.” The crowd on hand, comprised of both students and professors, also listening attentively to the broadcasting at the institution’s “auditorium-gymnasium.” Directed by Prairie View A&M College’s “history discipline,” the March 1949 edition revealed how the performance centered upon “the Negus Negusti, the king of kings, the conquering lion of the tribes of Judah of Abyssinia, Menelek II.” As Professor Woolfolk narrated the artistic demonstration, three others, including Lewis, who also wrote the Panther article, served as the performers. Lewis explained: “Menelek in the third year of his reign in 1893 signed the treaty of Ucciali granting to Italy an extension of Ethiopia back into the Abyssinian highlands. Because of a controversy arising out of the interpretation of article 17 of the treaty, Ethiopia, by the aid of France, had to fight to maintain her Liberty.” Lewis continued by revealing how Ethiopia beat Italy during “the battle of Adowa in 1896.” At this particular historical moment, therefore, the Ethiopians thwarted the invading European colonizer.[5]

In addition, the database Digital Commons@PVAMU throws light on later involvements of Woolfolk with Negro History Week at Prairie View A&M College. Between the 1950s and 1970s, for example, the evidence captures the esteemed Black professor’s commitment and activist initiatives to bring further awareness to the direct contribution of people of African descent to global history. In 1957, he worked alongside other Prairie View A&M academic groups, which included both students and professors alike. As the March 1957 edition of the Panther reflected, the collaborative efforts of these individuals for Negro History Week, overall, disseminated “a program of outstanding interest and informational value.”[6] Twelve Februaries later (1969), the student newspaper revealed to its readership that “the theme [targeted] for annual Negro History Week activities” was “The Changing African-American Image through History.” Arranged from February 9 to the 15, again Woolfolk was one of the main organizers and facilitators.[7] Finally, The Faculty Reporter: A Newsletter for Staff Members at Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical College, noted in its February 1971 publication that “Woolfolk and Dr. Purvis Carter [were] to guide our students in this important area of knowledge” regarding the institution’s Negro History Week programming. “We urge you to encourage your students to take full advantage of the human resources and the excellent material resources on the Negro which are available in the W. R. Banks Library,” the Faculty Reporter passionately advised. [8]

While not an exhaustive study of Woolfolk’s acclaimed career in the academy—nor his many contributions to the historical profession, this essay was an attempt to provide at least a brief sampling of Woolfolk’s decade’s long commitment to leading and facilitating Negro History Week programming at Prairie View A&M College. Indeed, the historical profession still desperately needs a book-length project on Woolfolk. One that demonstrates forcefully his contributions to PVAMU history, how he has advanced the study of African American history more broadly, his ongoing and fervent commitment to civil rights activism, alongside other topics of critical importance and salience.

Although Professor Woolfolk died approximately 26 years ago (1996), his legacy at PVAMU lives on. To be sure, the greatest visible representation concerning the late historian’s legacy is the George Ruble Woolfolk Social & Political Science Building, situated here on PVAMU’s beautiful and historic campus. Yet, Professor Woolfolk’s impact does not end there. He has left an impressive body of scholarship. Notable monographs include his 1976 text, The Free Negro in Texas, 1800–1860: A Study in Cultural Compromise; and one of his earlier studies, the 1958 project The Cotton Regency: The Northern Merchants and Reconstruction, 1865–1880. A historian who specialized in nineteenth-century African American history, Professor Woolfolk also published the first book-length study on the history of PVAMU. Meticulously researched with both sophisticated analysis and elegant prose, Woolfolk’s 1962 tour de force, Prairie View: A Study in Public Conscience, 1878-1946, demonstrates another fine example of historical scholarship at its best.

In the end, the illustrious career of George Ruble Woolfolk on “The Hill” serves as both a testament and important reminder to all regarding the high quality of teaching, service, and scholarly production amassed by one of the most distinguished PVAMU professors of times past.[9]

Matthew G. Washington is an Assistant Professor of History in the Division of Social Sciences at Prairie View A&M University. His book manuscript “Jim Crow, Yankee Style”: Civil Rights and Working-Class Pottstown, Pennsylvania, 1941-1969, is under contract with the University Press of Kentucky.

[1] “Negro History Week Observed at Prairie View: Dance Pageant is Presented,” the Panther, 20, no.3 (March 1946): 1, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/758.

[2] For quote, see “Black Culture Month Activities Begin February 1,” the Panther, L, no. 11 (January 1976): 1, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/154. For biographical data on Woolfolk, see Randolph B. “Mike” Campbell, “Woolfolk, George Ruble,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/woolfolk-george-ruble. On history of PVAMU, see George R. Woolfolk, “Prairie View A&M University,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/prairie-view-a-m-university.

[3] Campbell, “Woolfolk, George Ruble.” On Great Depression and WWII periodization, can see, for instance, “Great Depression and World War II, 1929-1945: Overview,” Library of Congress website, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/overview/.

[4] On database, see “Digital Commons@PVAMU: A Repository of Archives, Research & Scholarship,” Prairie View A&M University website, accessed January 28, 2022, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/. For “The Hill” quote, see Meredith Mohr, “‘The Hill’ We Climbed: Professors initiate collection of essays on PVAMU’s history,” August 17, 2021, Prairie View A&M University website, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.pvamu.edu/blog/the-hill-we-climbed-professors-initiate-collection-of-essays-on-pvamus-history/.On Woolfolk’s early involvement regarding programming, see “Negro History Week Observed at Prairie View,” 1.

[5] Hilliard G. Lewis, “Prairie View Joins Celebration,” the Panther, 23, no. 3 (March 1949): 2, 4, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/802.

[6] “Negro History Week Observed,” the Panther, 31, no.6 (March 1957): 2, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/723.

[7] “Negro History Week Activities Scheduled,” The Panther, XLIII, no. 9 (February 1969: 1, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/pv-panther-newspapers/38.

[8] Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical College, “Negro History Week,” The Faculty Reporter: A Newsletter for Staff Members at Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical College, 4, no.5 (February 1971), 2, https://digitalcommons.pvamu.edu/newsletter/475.

[9] For “The Hill” quote, see Mohr, “‘The Hill’ We Climbed.” For further data on Woolfolk, see Campbell, “Woolfolk, George Ruble.”