It is customary when celebrating Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday to speak of his accomplishments, speeches and sermons, and his national and global impacts. This year’s recognition of King’s life and legacy will certainly be no different. However, as we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, it’s fair to examine the social and political environment that shaped King’s life and work compared to that in which we live today.

For many generations, scholars have debated the origins and meaning of Jim Crow segregation. More so, scholars continue to examine the vile institution of American slavery. There’s no doubt that slavery and Jim Crow were effective tools in the subjugation of African Americans. King was born at a time when America struggled with rampant poverty, homelessness, and unemployment. During his formative years, America entered a global conflict with the self-declared goal of defending democracy and the rights of individuals to self-determination. The aftermath of that global conflict with the demise of Adolf Hitler, perhaps the most despicable national leader of the twentieth century, gave Americans hope that self-determination was an achievable goal. King lived in this America.

In the years following World War II, America celebrated the victory of democracy, the economy was surging, and the new technology of television beamed American values across the globe. But this was also the same America in which the black community continued to suffer the indignities of social and political ostracism.

Our history is rife with images of the atrocities committed by those sworn to prevent the civil recognition of African Americans into the broader American community. Without fear, these racists declared their intent to continue fighting racial integration one hundred years after the end of the American Civil War. King lived in this America. Thankfully, he, and millions of African Americans, lived to see President Lyndon Johnson sign legislation (Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965) that seemingly brought an end to Jim Crow and the ostracism of the black community forever. Oh, Happy Day!

In the decades since the Voting Rights and Civil Rights legislation, the black community has made tremendous strides towards achieving the American dream. The high school graduation rate of blacks (male and female) between 25 and 29 is slightly over 92 percent. That’s a nearly 38 percent increase from the 54 percent high school graduation rate in 1968. Likewise, the rate of college graduation for the same population also increased by almost 14 percent (9 percent in 1968 and 23 percent in 2018).

An examination of economic markers also reveals that the black community has made significant gains since the apex of the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s. The black unemployment rate increased between 1968 and 2018. But that increase was less than one percent. Similarly, the poverty rate for the black community decreased by 13 percent. However, increases were seen in median hourly wages (plus 43 percent) and median household wealth (plus 606 percent).

Such data seemingly prove that the condition of the black community has improved since the demise of Jim Crow more than 50 years ago. However, a closer examination indicates that the black community still lags behind whites. Even though the college graduation of blacks between 25 and 29 years old (male and female) is 23 percent, for whites, it’s 42 percent. The unemployment rate for blacks is over seven percent compared to under four percent for whites. The median hourly wage for blacks in 2018 was slightly under $16, while the median hourly wage for whites was just over $19. The median household income (in 2016 dollars) for blacks was just over $40k, and the median household income (in 2016 dollars) for whites was over $65k. The homeownership rate for whites in 2018 was 71 percent, while the homeownership rate for blacks was 41 percent.

However, perhaps the most distressing statistic since King’s death involves what we now refer to as the “prison pipeline.” In 2018, the incarcerated population (per 100,000) for blacks was 1,730 and only 270 for whites.[1] Scholars have examined the negative impacts of President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, and First Lady Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign in the 1980s. These policies decimated the black community as mandatory prison sentences for minor drug offenses not only destroyed families but destroyed faith in the very democracy that is the bedrock of America. As my grandmother would say: “one step forward, but two steps backward.”

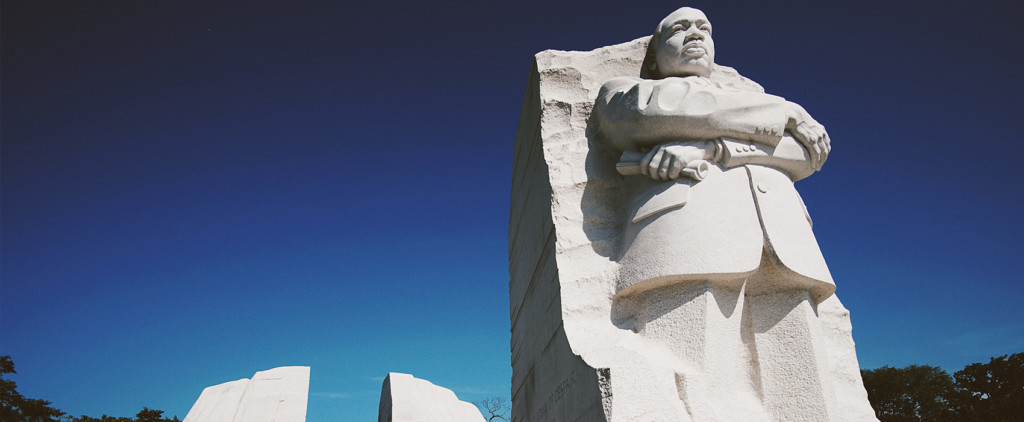

There’s no question that Dr. King deserves the recognition and accolades that we can bestow upon his memory. He was one of a select few that changed American society for every American. He reminded white America not to forget those who were not as fortunate as they were. This rebuke echoed Jesus’ words when he said, “The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.’”(Matthew 25: 40 NIV)

More than a half-century after his violent death, we celebrate Martin Luther King’s birthday. However, we also recognize that, for too many blacks, America still resists accepting the humanity and equal citizenship of blacks. Today’s frequent use of law enforcement as a tool in social controls harkens back to the slave patrols of the antebellum era. This has become a constant reminder that many whites still view blacks as socially inferior and politically undeserving of participation in this country’s democratic processes.

Dr. King, we love you, and we will continue to work towards your “dream” where race is not a social and political hindrance but ultimately an asset to understanding our better selves.

Ronald E. Goodwin, Ph.D., is the history program coordinator in Prairie View A&M University’s Marvin D. and June Samuel Brailsford College of Arts and Sciences.

[1] https://www.epi.org/publication/50-years-after-the-kerner-commission/. Accessed January 13, 2021.