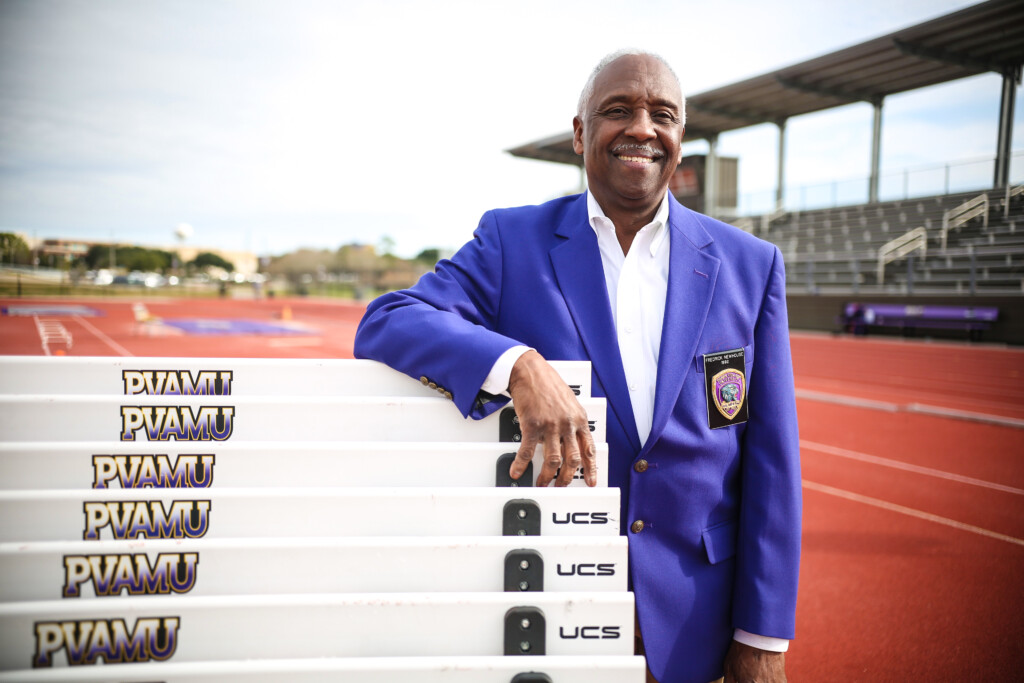

At the end of his senior year at Prairie View A&M University in 1970, Fred Newhouse got an unexpected recognition. It had nothing to do with his degree in electrical engineering or the fact that he was a three-time All-American and national champion in track and field. Indeed, it was not even about his invitation to the 1968 Olympic Trials.

According to Newhouse, “School was out, people were leaving, and Austin Greaux, dean of the College of Engineering, called me to his office. He told me, ‘I want to give you an award. You didn’t meet the criteria for the other awards that we give in the Engineering Department, but I felt after watching you for four years that you deserve an award.’

“So, he created one for me, and he gave me a plaque. He called it the Humanitarian Award,” Newhouse said. “I valued him saying that much more than I valued being selected as Athlete of the Year. For him to single me out for what I call ‘making a difference in someone else’s life’ changed the course of my own life. It made me think differently about what’s really important.”

Fifty years later, Newhouse looks back on his “four miraculous years” at Prairie View. “I literally cannot explain what happened to me. I didn’t understand it or appreciate it when it was happening,” he said.

Newhouse chose to attend Prairie View after graduating as salutatorian from Galilee High School in Hallsville, Texas, in 1966. At the time, his senior class of 40 members was the largest in the black school’s history — 18 boys and 22 girls.

“My brother Lucious was at Prairie View when I graduated from high school. He naturally talked a lot about the good experience he was having. He told me the girls were pretty, and that sealed the deal for me!” Newhouse laughed. “My high school counselor also pressed me to consider Prairie View. It was during that transition period of integration. There were students in the class before me who had gone on to predominantly white universities. I did have the opportunity to apply to those schools as well.

But, I decided that I wanted to major in engineering, and there were only two schools with engineering programs that accepted me — the University of Texas at Arlington and Prairie View.”

Newhouse grew up living with his grandparents, David and Dolly Newhouse. Their only income was from farming, and there were no savings for his education.

“I came to Prairie View on the Work Study Program. They took me in, gave me a room and meal ticket, and put me to work. They enrolled me

in some remedial classes for that first summer after they looked at my ACT score and saw that I needed help in English and history. My strong areas were math and science. I was assigned to the janitorial staff in the engineering building, where I worked 20 hours a week. It was a minimum-wage job, but they took the money I made and applied it toward my tuition for the fall semester.

Newhouse played sports in high school. But he spent the majority of his childhood years in church, working on the family farm, and in school.

“If you were involved in school activities, you could get out of working in the fields. So, I was involved in all kinds of school activities,” he said with laughter.

“My high school coach, Walter B. ‘Chess’ Edwards, coached everything with no assistance. He had played baseball for a year with the Los Angeles Dodgers and had played in the old Negro League. He would take the fastest guys off the baseball team and take us to the track meets on Saturdays. We never practiced track, and he never really coached track.”

At Prairie View, Newhouse decided to try sports after getting his first-semester grades. “They were OK. They weren’t good enough for my grandmother, but I didn’t flunk out of school. I decided I would go out for the PV baseball team, and I made it as a third-string right fielder.

At the time, Prairie View’s baseball team wasn’t very good.

“We were losing like crazy. We played a four-game series at Southern University, where they swept us. They beat us bad,” Newhouse recalled. “After that game, I think the baseball coach decided he needed to get rid of some of the dead wood. He took us over to the track to literally run us off.

“He put the fastest guys on the track, and I was in that group. The coach said, ‘OK, whoever wins doesn’t have to run anymore today. For the rest of you all, we’re going to run until there’s one man standing.’ The track coach is standing in the distance with his track team and his stopwatch. We ran in baseball uniforms and tennis shoes on a cinder track,” said Newhouse.

Newhouse later learned that the track coach informed the baseball coach that he ran faster than some of his track team members on scholarship.

“The next day I came back to baseball practice, and the baseball coach looked at me and said, ‘You’re fired,’” Newhouse recalled. “I said to him, ‘What did I do wrong? I did everything you said.’ “He said, ‘Yes, I know. You run track now. You don’t play baseball anymore,’” Newhouse remembered. “He told me to turn in my baseball uniform and cleats, and he cut me from the baseball team. I told him, ‘Listen, I didn’t come down here to run track. I guess I’ll go on back and concentrate on my engineering.’”

Later that night, two varsity squad track team members went to Newhouse’s dorm and found his room. “They said, ‘Hey, we saw you run yesterday, and we believe you can help our freshman team. The track coach wants to talk to you.’

“So, the next day, I went and visited with Coach Hoover Wright. He told me if I made his team and got one point in the conference meet, he would give me a track scholarship,” Newhouse said. “I told him I would think about it. He said, ‘Good, because this weekend we’re going to the Grambling relays, the weekend after that the Kansas relays, and after that the Drake relays in Iowa.’”

Newhouse complied.

“Basically, I joined the track team because it gave me a chance to travel. I didn’t get a point in the conference meet,” he remembered. “I ran my lifetime best in the 100-yard dash in the preliminaries of the conference meet, and I got last place in the heat. I didn’t even make it to semifinals.”

“I said, ‘Coach, I ran my lifetime best,’ and he said to me, ‘I know.’ I told him, ‘I’m sorry I didn’t get a point.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I know.'”

As the season progressed, something odd happened that would change the trajectory of his career in track and field.

“We kept running, and members of the track team started getting injured. We were getting ready to go to the national championship in the spring of 1967,” Newhouse recalled. “I wasn’t scheduled to go because I wasn’t nearly one of the fastest guys on the team. We had made the national championship in the 4 x 100-yard relay, and it got down to me being just a healthy body.

“The coach said, ‘Hey, do you want to go to the national championship? You can run the first leg.’ I said, ‘Where is it? Coach Wright said it was in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I had never been to South Dakota. So, I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll go.’

“We went and got third place. It was good for six points for the team, which meant I got a point-and-a-half. The next school year, he paid my tuition and fees,” Newhouse said.

In February 1968, PV’s track team participated in the NAIA Championships in Kansas City. Coach Wright insisted Newhouse move up and run a longer distance.

“He put me in the 400-meter dash. I won and set the NAIA record,” Newhouse said. “You’ve got to put this in perspective. In May of 1966 — 18 months earlier — I couldn’t get out of my district championship in anything. I went from not being able to make competition finals in high school to being the national champion and record holder in the NAIA.”

Newhouse, amazed by the turnaround, said he would like to think that such a rapid, unbelievable change might have been associated with Wright’s coaching.

“But nobody can coach that. We didn’t have great facilities. We trained by running around the top of the gymnasium, the Baby Dome. It’s a wonder we didn’t kill ourselves up there,” Newhouse said. “I grew 2 inches and put on between 15 and 20 pounds. None of that can explain such a dramatic change. It was only the grace of God. It had to be a part of God’s plan.”

Then, in late May 1968, the Prairie View track team won the outdoor championships of the NAIA, where Newhouse had placed a disappointing third place finish in the 400-yard dash. He was summoned to Coach Wright’s office.

“He said, ‘You’ve been invited to the Olympic trials.’ I said, stunned, ‘I thought you had to win a championship to get invited to the Olympics trials. I got third place,'” Newhouse said. “Coach Wright said, ‘Yes, that’s right. But they went through all the runners in the United States and picked out those who had won championships, and they ended up with 15 runners. They wanted 16 to fill the field, so they went to the next- fastest time, and it’s you.'”

“I said, ‘Coach, I’m in summer school.’ He said, ‘Yea, I know.’ I said, ‘And I’m not training right now.’ ‘Yea, I know,’ Wright said in return.”

The Olympic trials were in Los Angeles, so I asked him how we were going to get there.

The Olympic trials were in Los Angeles, so I asked him how we were going to get there.

We normally would drive in his station wagon. He said they were going to send me an airline ticket. I thought to myself, ‘I’ve never been on an airplane before.’ So, I said, ‘Yea, I’ll go,'” Newhouse said.

Newhouse had not planned for a turbulent flight.

“The plane was bouncing all over the place. It was raining, and I was nervous all by myself,” Newhouse recalled. “So I asked the airline stewardess for a magazine. I told her I like to read sports, so she grabbed a copy of Sports Illustrated. It was an old issue, and on the cover was a picture of a runner named Larry James, who had just set the world record indoors.

The name of the article was “The Mighty Burner.” The article made him seem bigger than life.

In Los Angeles, I walked into the hotel where all the athletes were staying, and I saw a guy I had just run against, John Carlos, from East Texas State University. I asked him where the heat sheets were so I could see what race I was in and where I was running. He said, ‘They’re right over there on the board.’ I go over to the board, and I find my name… and guess who is in my heat? Larry James.

“I said, ‘Oh Lord, no!’ That put a lot of pressure on me,” Newhouse remembered.

“So, I run the race, and I lead the race until I get close to the finish line. And then five guys pass me.

Afterward, I’m sitting over on the grass, putting on my clothes, and this guy comes over and sits down beside me. His name is Larry James.

He said, ‘You’re Fred Newhouse, aren’t you — from Prairie View?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘Man, I wish I had your speed.’ I thought to myself, ‘The Mighty Burner wishes he had my speed.’ It changed my whole perspective on track and field.’

James went on to win the Silver Medal in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. “I was just running to stay in school and get my tuition paid,” Newhouse admitted. “Never in my wildest dream did I think I would have any potential to be an Olympian.”

The next year, teammate Felix Johnson went to the national championship and made a U.S. team that competed in Japan. “He came back; he was my roommate. Every night, with the four of us in the room, he talked about his experience going to Japan — the culture, the language, and the food.

“I knew there was a lot more that track and field had to offer. I just hadn’t had that type of exposure.”

Suddenly, Newhouse began to focus his energy, and everything got better, including his grades. In January 1970, he set the world record in the Astrodome in the 400-meter dash with a time of 45.6 seconds.

“Later that year, I went to the national championship and made my first national team. We did a tour of France, Germany, and then Russia in the summer in dual meet competition,” Newhouse said. “The coach of the team was Dr. Leroy Walker from North Carolina Central University, the first Black man to lead a national team. Ironically, Walker’s first coaching job was at Prairie View.

“He was elegant, professional, and friendly. He was a great coach,” Newhouse said of Walker. “It was clear that he was head and shoulders above anybody on either of these staffs — French, German, Russian, or American. Every Black kid had their chest stuck out.

“We were so proud of him, and he was such a great role model. He became one of my mentors,” Newhouse said.

Thanks to another man at Prairie View, Newhouse got other unmerited privileges. Frank Yepp, who was in charge of student employment, occupied an office in the engineering building. He assigned Newhouse to his office as a clerk. “I worked in between my classes. The majority of them were in the engineering building,” Newhouse said. “Mr. Yepp told me, ‘If they don’t have something for you to do, you should go to the file room and study.’ So I did, especially during track season. That environment allowed me to keep up my grades while spending a lot of time on the road running track.”

Newhouse graduated from then Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (PVAMU) in 1970.

He believes God’s grace continued to chart a path forward in track and field even after he left Prairie View.

“I didn’t make an Olympic team until 1976. After college, I spent two years in the U.S. Army after I was drafted. I was destined for Vietnam, but God’s favor kicked in again,” he explained. Guided by grace, Newhouse ended up at West Point military academy.

“For the next two years, I did nothing but train on the army’s track team and run track meets around the world,” he said.

He would go on to win gold and silver medals at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, Canada. He also earned a master’s degree in International Business from the University of Washington in Seattle.

He has held positions with Exxon Mobile and Valero in Texas, California, and Louisiana. With all of his accomplishments, travels, jobs, and appointments to boards, Newhouse said his greatest achievement is helping others.

“I try to give back in everything I do. Currently, I serve as a trustee on the Walker County Soil and Water Conservation District, where we help farmers and ranchers through USDA programs,” he said. “I serve on a statewide board known as Texas Rural Communities, where we provide loans to people in rural communities who can’t get loans elsewhere. We take the interest earned from these loans and give it back to nonprofit organizations in rural Texas communities. I also serve on the board of Today’s Harbor, a residential facility for kids who find themselves in very difficult situations.”

Now in his early 70s, Newhouse stays active with his wife, Rhonda, whom he met while attending PVAMU, and his two daughters, a son-in-law, and two grandsons. He continues to officiate national and international track and field competitions and runs a cattle ranch near New Waverly, Texas.

He and his wife also host youth seminars at their ranch. “Over the past 11 years, we’ve hosted more than 500 kids,” he said. “The goal of these seminars is to expose urban kids to rural environments and the importance of maintaining clean water, clean air, and later clean environments such that man and all animals can live freely, grow their young in habitats that allow for them to survive and maintain good lives,” Newhouse said. “Our goal is to let students know the importance of good, normal conservation practices like not littering the environment. This is a simple way for all of us to make a difference in the lives of others.”

“Making a difference in someone else’s life is bigger,” he said. “I have always and continue to support PVAMU by being involved with campus activities such as the PV Relays; serving as one of the founding trustees on the Prairie View A&M Foundation; hosting annual educational activities at my ranch in coordination with the Ag College for PVAMU students and doing same for Urban Ag students in the Houston area. And lastly, my wife and I find great pleasure in giving money to the university on an ongoing basis.”

This article by Sammy G. Allen originally appeared in the summer 2020 edition of “1876.”

-PVAMU-